When Rose de Freycinet was in Rio de Janeiro in December 1817 and January 1818 she saw very little of the crioulas, the women of pure Portuguese descent, but what she did see did not impress her. She was shocked by their behaviour during the church services, which were treated as occasions for intrigue and display rather than as festivals of religion, and also by their attitude to their marriage vows, which they took very lightly. She had a much better opinionof of their Spanish-speaking sisters, the criollas of Montevideo, a city she visited in May 2020, but had she been, at that time, transported by some miracle across the continent to the city of Quito, she might have met there a criolla whose conduct she would have found equally shocking, but for very different reasons. This was a woman then of an age very similar to the age she had been when she was smuggled aboad the Uranie in Toulon, but one who not only did not pay lip service to religion but argued forcefully against it. Moreover, very unlike Rose, the man this woman had chosen to devote her life to was not her husband and, despite her devotion to him, she was rumoured that she was not averse to sharing her bed with others.

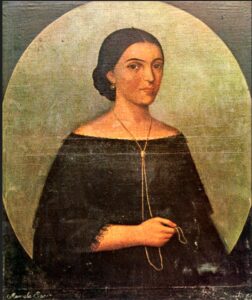

Manuuela Sáenz in 1823. This portrait, painted by Pablo Duarte in 1825, is likely to be far closer to the real Manuela than the more commonly circulated picture showing her wearing the sash of the Peruvian order of the Knights of the Sun, in which she is dressed in a gown that wouldnot have been in fashion at the time.

On 24 May 1820, the forces of the Republic of Guayaquil commanded by Antonio José de Sucre defeated a Spanish army on the slopes of the Pichincha volcano, just outside Quito, and entered the city. On 22 June the victory was celebrated by a parade and a ball that was attended by, among a multitude of others, a man newly arrived in the city and a woman who, although she had been born there, had returned only a few weeks before, concernin some matters of inheritance. The man was Simon Bolivar, known as El Libertador. The woman was Manuela Thorne Sáenz, and she had had been prominent in the revolutionary movement, but in Lima, not Quito. At the ball she was proudly wearing the sash of a Caballeresa del Sol, the highest honour the Peruvian Republic could bestow, awarded in recognition of her services to the revolutionary cause and in particular for her part, the previous year, in persuading the troops of the royalist garrison in Lima to change sides and support the republic. Whether her success in doing so was due principally to her acknowledged beauty or to the fact that, according to the Peruvian author Ricardo Palma, she was a mujer-hombre, a ‘man-woman’, who smoked and drank like a soldier, rode horseback like a man, was at home in in the rowdy world of barracks and military camps and was “a ‘mistake of nature whose masculine spirit and aspirations were embodied in female form”, is a matter for speculation, but one thing is certain. Once she had met Bolivar, she was lost for ever to James Thorne, her wealthy English husband. He continued to write despairing letters to her, to which she replied, if at all, in unencouraging fashion. In what must have been one of her last replies to him, since she was evidently tired of doing so, she wrote:

No, no, not again, man, for God’s sake! Why do you make me write back to you, and so break my resolution? Look, what good are you doing, by giving me the pain of telling you a thousand times no?

Sir, you are excellent, you are one of a kind. I will never say anything different about you. But, my friend, leaving you for General Bolívar is something. Leaving another husband without your qualities would be nothing.

And so, you think that after being the General’s favorite for seven years, and with the certainty that I have his heart, I would rather be someone else’s wife, the lord’s, the son’s, the holy spirit’s or the Holly Trinity’s wife?

…I know very well that nothing can unite me to him under the auspices of what you call honour. Do you think me less honourable for having him as my lover and not my husband? Oh, I do not live by the social concerns invented for mutual torture!

Leave me alone, my dear Englishman. Let’s do something else. In heaven we will be married again, but on earth no . . . Do you find this agreement wrong? If so, I would say that you are hard to please.

In the celestial homeland, we will enjoy an angelical life, a spiritual one (because you as a man, are very heavy). There, in heaven, everything will be English style, because a life of monotony is reserved for your nation (in love, I mean, because in other ways . . .who is more clever in trade and navies than the English?).

They take love without pleasure, conversation without humour, and walks without vigoro; they greet with bows and curtsies, get up and sit down with caution, joke without laughing. These are divine formalities; but I, a wretched mortal, who laugh at myself, at you, and at these English solemnities, how badly I would do in heaven!

It would be as bad as if I would go live in England or Constantinople, because I feel that in these places’ men are tyrants towards their women, although you were the exception. Yet, you were very jealous. I do not want that! Now, do you dare to say that I do not have good taste?

But no more joking. Formally and without a laugh, in all sincerity, purity and seriousness of an English woman, I declare that I will never live with you again. You are Anglican, I am an atheist, Consider that a strong religious contradiction for our union. Yet, the strongest impediment is that I love another man. Don’t you see the formality of my thinking?

Your constant friend,

ManuelitaH

Her opinion of England,would have undoubtedly been endorsedbut by some of those who accompanied Rose on her journey around the world, and certainly by Jacques Arago among them, but if Manuela had ever been as far south as Valparaiso and had met Thomas Cochrane, she might at least have admitted that not all Englishmen were boring. And if she had met his wife Kate she might well have found that they were two of a kind.

It has to be said that Thorne must have known, or at least should have guessed, what he was letting himself in for when he married Manuela. Born in December 1797, her life had begun inauspiciously; because she was illegitimate, and her mother, disowned by her family on that account, died only a few weeks after she was born. Fortunately for her, her father, a prominent member of the Spanish aristocracy of Quito, had then acknowledged her as his daughter and had ensured she received an education befitting a member of his own class, with the nuns of the Convent of Santa Catalina. However, according to most of the accounts of her life (of which there are many, but not always reliable ones), she had to leave their care rather precipitately when it was discovered that she was having an affair with a young army officer. She had also already learned to be an expert horsewoman, which was not usual among the criollas of the time, although not unknown, and at some quite early stage in her life, and probably before her marriage, she had demonstrated the character so disapproved of by Pradar..She was not a conventional choice for a conventional man like Thorne, and once she had met Bolivar, an affair was almost inevitable. What was remarkable was that it lasted to his death and beyond. Effectively her life thereafter was one long lament for her loss.

She did, however, also have some regrets about James. When he was brutally murdered in 1847, she took the news to her heart. In a letter quoted by Prada she wrote

I am sick with the news of the horrible murder of my husband, because although I did not live with him I cannot be indifferent to this tragic event.

He had, it transpired, left her a considerable legacy, but she declined to accept it, even though she was by that time living in poverty in exile in Paita in Peru, where she died nine years later in a diptheria epidemic.