Rose de Freycinet’s journal was written to be read by one person only, her close friend Caroline de Nanteuil, and when the expedition finally returned to France it was to Caroline that it went. It remained in the de Nanteuil family archives until 1910, when Caroline’s grand-daughter decided that it should be returned to the Freycinet family and handed it to Baron Henri de Freycinet, the grandson of Louis’ elder brother Henri. In 1923 Charles Duplomb, a naval historian who was also an honorary director of the Ministère de la Marine, learned of its existence and wrote to the Baron, who was by then in his mid-sixties and had himself been a Capitaine de Frégate, asking on behalf of the Société de Géographie de France and the Académie de la Marine for his permission to have it published.

The Baron’s initial response was not encouraging. He pointed out that the journal mentioned many figures prominent in recent history by name and conceded only that some extracts might be published after rigorous editing. Only after protracted negotiations was it agreed that an almost complete version could be released but the editing requirements were not relaxed and it was to be an almost private publication. What appeared in 1927 was a very limited edition of 500 ‘ordinary’ copies and just fifteen de luxe copies. By the time friends, family and major libraries had received their copies there were very few available for general sale.

When Duplomb first contacted the Baron, he may not have known that the diary, which now resides in the Mitchell Library in Sydney, was incomplete. It had been written in a series of notebooks and one of these was missing. It was the one that covered the voyage from the departure from Dili, on the north coast of Timor, to the visit to Sydney. Had the diary been the only source, what remained of it might not have seemed worth publishing, but there was an alternative. Rose had also written a series of letters to her mother, and copies of those describing the voyage as far as Sydney have survived. These too have ended up in the Mitchell Library, but long before they did so they had been used by the editors to fill in the gap. Where the two overlapped they used only the diary account, and made a very poor job of the join between the two, leaving the early part of the visit to Sydney unrecorded in what they eventually published. It must, however, be regarded as very fortunate that it was the Dili to Sydney part of the diary that was missing and not any later part, because the last of the letters in the collection was the one given by Rose to friends in Sydney just before she left, to be sent to France at the first opportunity.

Did she then stop writing to her mother? It would have been completely out of character, and we have her own testimony to the fact that she did not. In her diary she recorded that as they were about to leave the site of the wreck of the Uranie in Berkeley Sound she gave three letters to the captain of the English whaler, the Sir Andrew Hammond, which had just arrived on its way north and expected to be in London in just sixty days. One of the letters was to her mother, another to her father-in-law, Pierre, and the third to Caroline, and in her diary she wrote ‘How I wish that I could put myself in one of those letters and be in France in 60 days’. We can assume that all three letters arrived, because we know at least one of them did but it took much longer than 60 days to reach its destination. It was the letter to Pierre de Freycinet, and it cannot have been in his hands much before the 2nd of August 1820, more than three months after Rose left the inlet she knew as the Baie de France.

The diary entry in which Rose mentioned sending letters to France via the Andrew Hammond. Image digitised by the Mitchell Library, Sydney, catalogued as FL687093.

Although by convention the letter was addressed to Louis’ father, the head of the household, there can be little doubt that it would have been read most avidly by his mother, the former Elisabeth Armand, and having read it she hastened to make a copy and send it to Louis’s elder brother Henri, then staying with his own parents-in-law in Rochefort, where his first son had just been born. This letter was preserved in the Freycinet family archives and, almost predictably, again found its way to the Mitchell Library. It began with enquiries about the latest addition to the Freycinet clan.

“We are still without any news from you, my dear friend, and its absence is truly very painful to us, because we never stop thinking of our dear children in Rochefort and we would like to be sure that they are now in perfect health and that they are as happy as they deserve to be. I implore you to give us some sign that you are alive by writing us a very small letter, so that we can read its precious words and learn that your health, that of my lovely daughter and of our dear little child, are as good as we could wish.”

With that preliminary out of the way, Elisabeth hurried to pass on the news she had just received. We can imagine that she would have done this as quickly as possible, to set minds at rest, because her letter makes it clear that the wrecking of the Uranie was already known in France, no doubt in very garbled form.

“I am sure of the pain that you must have felt when reading in the press of the horrible misfortune that befell our dear voyagers. We ourselves were very dismayed but fortunately were not kept long in cruel anxiety, because a letter that we received at that very moment from these dear children, gives us life again, and I hasten to share it with you; it is my daughter-in-law writing to your father. The letter is dated April 20, 1820 and to make you better aware of the contents, I will copy out the main pars as well as the few lines which were added by our dear Louis; but what thanks we must give to Divine Providence for having preserved these dear friends in the midst of every danger! Our dear Louis displayed great skill and admirable composure under these circumstance, which should without a doubt place him in the first rank of navigators.

According to their calculations, they still hope to be back in France next autumn. Pressed by the departure of the post and wishing to take advantage of it today, I finish my little letter. Farewell, dear Freycinet, farewell my lovely daughter, receive together the tender caresses of your loving mother.

Your father sends you thousands and thousands of greetings. We give our dear little baby a warm hug and we offer Monsieur and Madame Berar our very affectionate and sincere salutations”

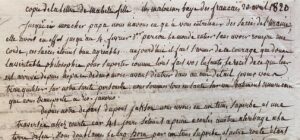

The beginning of the copy of Rose’s letter from Berkeley Sound that forms part of Elisabeth de Freycinet’s letter of 2 August 1820 to Henri de Freycinet. Researcher’s image of the letter archived in the Mitchell Library, Sydney under Call Number SAFE/MLMSS 10565/Box 1/Folder 1/Item 18, Record Identifier 9Nar3MKY/

With that news safely delivered, Elisabeth then added a copy of Rose’s letter. It was very brief, but of the three letters sent, this was probably regarded by Rose as the one in which details were least needed. Her letter to her own mother would surely have been longer.

Elisabeth wrote:

Copy of the letter from my daughter-in-law. Baie de France, Iles Malouines, 20 April, 1820

“Up to now, dear father, we have had nothing you to tell you about except the triumphs of the Uranie. In fact, until this 4th of February she had sailed around the whole world without even a rope having snapped. This success was very pleasant ….. today one must call upon the courage that true philosophy provides, to endure everything that has happened to your children in the space of two months. Before going into any detail, I want to reassure you as to our personal safety: we are all well, and on an American ship in which we are being taken to Rio de Janeiro.

After our departure from Port Jackson we had superb weather and a quite short crossing because it was barely forty-one days before our landfall on Tierra del Fuego: we rounded Cape Horn in superb weather, and our route being favourable we immediately entered the Le Maire Strait in order to relâche in Cook’s ‘Bay of Good Success’ to make observations. We had barely dropped anchor when a terrible wind began to blow.

We immediately cut the cable and raised sail as quickly as possible because the anchor had dragged the vessel to within a cable of the rocks that border the coast. We had a terrible weather and seas for two days, with a wind so strong that it did not allow a single sail to be set, despite which the ship made a considerable progress and we found ourselves close to the Falkland Islands. With the wind against a return south, Louis decided to relâche on these islands, which are little known and of which he had only very bad charts. On entering the bay, the Uranie struck an uncharted rock and the damage done was so considerable that despite four pumps the Uranie would certainly have sunk if a suitable place had not been found to beach her; once she had run aground on the sand all the instruments and the work of the expedition were easily saved. Every possible effort and means were used to right the poor Uranie and repair her, but all in vain. A small vessel was then constructed from the chaloupe, rendering it able to sail for some time. It was to be manned by one officer and the best of the crew of the Uranie and was going to head towards Rio de la Plata to look for a vessel capable of transporting us and our cargo, but in the meantime an American vessel which had also been damaged at Cape Horn and had entered the bay to make repairs, agreed in return for payment to take us to Rio de Janeiro. I am writing to you from that ship.

Heaven then brought us the arrival of another vessel returning from the whale fisheries, which only stopped to take on water, and which provided us with an opportunity of sending our dispatches immediately to England, and so to France.

As we have little time to write, we cannot ourselves let my brothers know of our situation, be kind enough, my dear papa, to give them our news and to give them a thousand hearty embraces on our behalf.

RF

Brief, but very much to the point. What the letter did not reveal was just how dangerous the journey home was going to be, in the cramped quarters of the barely seaworthy Mercury (renamed La Physicienne after Louis had purchased it while en route to Montevideo). But Rose herself could not have anticipated that, at the time she wrote.

Elisabeth then went on to copy the even briefer note that Louis had sent. It went:

“I use today, my dear papa, to assure you of my sincere affection, we are about to set sail and time prevents me from going today into greater detail. We have experienced terrible misfortune but, happier than La Pérouse, I have at least the satisfaction of reporting that out of a hundred and twenty people, not one was lost in my disaster. I have also saved all the papers, all the instruments and everything that I could have hoped to bring back to France, my entire expedition except for the ship, which is little compared to the rest.

Goodbye, my dear papa, goodbye, my dear mother. I have written nothing to my brothers or my friends, for want of time. Send them, I beg you, my wishes for their happiness.”

He would have sent other letters back with the Andrew Hammond, but they would have been official ones. It would have been these that provided Paris with the first news of the disaster, and which had gave rise to the rumours Elisabeth was so anxious to correct.