During the whole of her three-year voyage around the world, Rose de Freycinet kept a journal for her close friend Caroline de Nanteuil. She gave it to her on her return, but not all of it has survived. The whereabouts of the parts that dealt with the period from the Uranie’s arrival in Dili in the then Portuguese eastern Timor and its arrival in Sydney in New South Wales (comprising at least one notebook and possibly more) are unknown. They are probably lost for ever. To fill this gap, Charles Duplomb and the then Baron de Freycinet, the editors of the first published (1927) edition, used Rose’s letters to her mother, as transcribed, probably after her death and possibly with significant editing, by her husband. They edited these letters much less heavily than the diary, and made relatively fewer omissions, but there was one rather obvious one. The section that they labelled Chapter VIII ends on the 17th of November 1819 with the Uranie still at sea, trying vainly to enter Port Jackson against contrary winds, and their Chapter IX begins with Rose and Louis already in Sydney receiving ‘many invitations that we were obliged to refuse’. The surviving manuscript tells us a little bit more, because it begins mid-sentence with:

….. the Bathurst plains. The weather was fine during the return from Parramatta. [FL687029]

The first three words provide a date, because we know from other sources that what was being described was the meeting between Rose and Louis, who were on their way back to Sydney from a two-day visit to the Macquarie family in Government House, and Quoy, Gaudichaud and Pellion, who were setting out from Sydney on their ten-day excursion to Bathurst. The meeting took place on the 27th of November, more than a week after the Uranie anchored in Neutral Bay. Was that week devoid of incident?

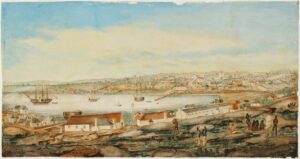

Sydney Cove, from Bunker Hill. (image State Library of NSW – XV1 / 1803 / 1). The painting, by George William Evans, shows Sydney as it was during Louis de Freycinet’s first visit, in 1803. It is just possible that one of the houses in the fregrond is the one he rented fifteen years later.

Absolutely not. ‘Other sources’, which include the copies of Rose’s letters to her mother, show that there was much coming and going. The usual formalities had to be observed, and that took time, and on the 23rd Governor Macquarie paid an official visit to the corvette. By then the de Freycinets had established themselves in a house on Bunker’s Hill (the Rocks district) overlooking Sydney Cove, which served also as an observatory, and on the 25th they travelled by boat to Parramatta, serenaded by a military band in a second boat.

There was one other significant incident during this period, and it might have been the one that persuaded the journal’s editors, continuing their fixed policy of making the published Rose a much less interesting person than the real one, to ignore what she wrote to her mother from Sydney, even though it would have filled a considerable gap. It included this paragraph:

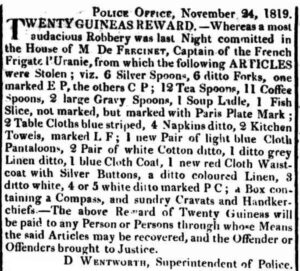

It is not, however, as if the happiness we enjoy here is unclouded except by the fear of seeing it end. For example, when we awoke in the morning four days ago, we learned that during the night our silverware, table linen, [the clothes] of our servants and other effects had been stolen from the ground floor of the house we are occupying. You know the purpose of this colony and the sort of people that abound here; you will therefore not be surprised by this mischief: can we not say that this is the classic land of criminality? It would be as amazing to not find thieves here as it would be to not meet Parisians in Paris or Englishmen in London. [FL877035; FL677037]

The announcement in the Sydney Gazette offering (in vain) a reward for the return of the de Freycinet silver. We learn elsewhere in the Gazette that the name of the thief was Thomas Jennings and that he was sentenced to serve out the rest of his life (which was likely to be short) in the Newcastle coalfields.

For some the reason the editors’ censorship did not, where this incident was concerned, extend to the journal pages, so that what was published in 1927, and was repeated in the Gerfaut edition of 2002, included the paragraph:

During my stay in Parramatta, I wished to go and say my goodbyes to Mme. Macquarie. Mme. MacArthur lent me her carriage and I went to visit her. The governor was too ill to see us it but his wife received us with extreme affability. …… She also told Louis that she was instructed by the governor to offer him the silverware that had been stolen from us or its silver equivalent; we absolutely refused it, in spite of numerous protestations and her contending, amongst the reasons why we should accept, that the police had been at fault and that the government should make good the loss, but we persisted [FL687035].

Bizarrely, the edited version, while retaining this reference to the silverware, which is almost incomprehensible without the information in the letter, confused Mrs Macquarie, who was being visited, with Mrs MacArthur, who had loaned Rose her carriage for the visit. In omitting the actual burglary, Duplomb and the Baron might, perhaps, have thought Australia in the 1920s to be more sensitive about its convict past than it actually was, and feared a diplomatic incident. Louis himself was more robust in what he wrote 100 years earlier, and had no hesitation in telling the story, with some additional information.

I hastened to take the necessary steps with the competent authorities to succeed in recovering what had been taken from me; Mr. Field seconded me with all his influence: but my thief was neither less informed nor less expeditious; he knew that, according to English law, a stolen object, once sold on the open market, could not be returned to its rightful owner until after its identity had been established; now, my silverware having already passed through the crucible, and being thereby transformed, had been acquired by a silversmith, and even resold a second time by the latter. The culprit, however, was discovered: he was, I am told, one of the most skilful and subtle crooks in the country. Already convicted for his previous offences, he was liable to forced labour in the coal mines of the Hunter; but for this purpose a judgment was necessary and, whatever the outcome, it seemed obvious that it would do nothing useful to me. However that may be, a constable was ordered to watch over our observatory in the future, and to guarantee our instruments against any attempt of the same nature. [Historique (Tome II, Partie II, p269)]

It was a lesson for Louis about the perils that surrounded innocent sailors adrift on dry land, but it was not well learned, because on his second visit to Rio de Janeiro he was robbed again, and this time some of the scientific instruments went missing.