Having dealt with the case of the man whom he described as ‘an assassin’, even though an actual assassination seemed far beyond either his wishes or his abilities, Jacques Arago turned his attention to the real villains, the people he designated as ‘chevaliers d’industrie’ but whom, since industry seemed to form no part of their make-up, is translated here simply as ’cavaliers’. He started with one of the lowest of all practitioners of the art of fraud, and then worked his way up to the higher reaches of society.

I repeat. All classes of society have their experts, who freeze generosity in the hearts of those who would be generous and destroy the trust and confidence of those who have already been duped by swindlers or knaves. I found myself, a few years ago, the witness of a truly curious scene.

I am a storyteller. If you liten to me, I will tell you all about it in due course. But I also know how to listen.

Almost opposite the Café des Variétés, the habitual meeting place of a flock of men of letters who came each morning to tell each other of their successes and failures of the previous day, a poor blind man, with an obsequiousness that is to be found just there, and everywhere else, deafened the passers-by with a shrill and off-key song. Some simpletons, taking him for a former artist from the theatre in front of which he was chanting his litanies, held out a generous hand to him, and a small coin would fall into the begging bowl of a dog he held by a string. At each gift the grateful supplicant would say, as had the sacristan of a moment ago, “God reward you!” And this unhappy Belisarius would address the compassionate housemaid as “Captain”, the little girl whom a grandmother was teaching to give alms as “Madame” and the sergeant-major with a bushy moustache and chevrons on his arm as “Mademoiselle”.

One day, a child of seven or eight years old (an age at which, if one has been brought up in a school in Paris, one is full of mischief), a little rascal who had just bought a pair of scissors, stopped in front of the beggar’s raddled face and had the idea of testing, at the expense of this sightless man, the worth of his purchase. Snip! the string is cut. Immediately, without thinking of the crowd around him, the beggar rises, chases the child down the street, catches him after a thousand dodges, gives him a slap and a vigorous kick in the behind, returns to his dog, reties the string, and cries again: “Charitable souls, for a poor blind man, if you please!”

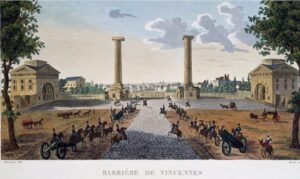

That day was not very profitable, and now our blind clairvoyant pursues passers-by with his sickly voice near the Vincennes gate in the customs barrier. A cavalier in rags!

Figure 1. The Vincennes gate and customs barrier. Lithograph from ‘Vues de Paris’, Henri Courvoisier-Voisin (1757 – 1830)

But let us change the scene.

Here are rich carpets, here bronzes by Ravrio, here silk and embroidery, here diamonds on bared breasts, red ribbons on suits by Staub or Lander. What elegant cavaliers! What graceful women! Listen, Demoustiers could not have written a better madrigal, Richelieu could not have been more scrupulously courteous. Is it all one family? One would say so, from the affability of the talk that strikes the ears. Are they brothers seeing brothers again? One would believe so, from the emotion of the embraces. What a wonderful evening I am going to spend! Gambling, to play rather than to win; dancing, to dance rather than to complete a seduction. Oh! I love life, and I bow understand the contentment of the rich.

Every Tuesday we meet here. Every Tuesday I will be among the first at the rendezvous. The joy of others is my joy. We are so happy to be together! Let us hasten then to enjoy everything, because life is short when lived in such intoxication.

But what is this? Great God, what is this bizarre disturbance? Furniture is broken, ladies flee in terror, we hear the sort of language more typical of the market halls. Two men confront each other, they threaten each other with their scowls, they exchange addresses, they leave. I follow the one more affected, the one who seemed most disturbed by this noisy affair, and offer him my sympathy. He was inspecting himself in the mirror of the anteroom, adjusting the knot of his tie. He ignored me, and then M. Jules de Rembrun accosted him.

“Well, my friend, how much did you get?”

“Only one hundred and fifty louis.”

“Not good! When is the meeting?”

“At eight o’clock”

“Where?”

“In the Bois de Boulogne.”

“I have an agreement with Ernest, who will act as his second. Once there, I will pick a quarrel with him; you know I am skillful, he will have to deal with me first, and so ….”

“I understand. Here, here is twenty-five louis.”

“And for Ernest?”

“That is fair, give him the same.”

“Until tomorrow.”

“Until tomorrow.”

The second returned.

“I have just spoken to your adversary,” he said in a low voice to the man concerned. “It is at eight o’clock. Be punctual – I never keep people waiting for such meetings.”

“We will be there, sir.”

So, three cavaliers against one honest man. There is no way out!

As with the heart, the mind has its affinities. I felt the need, after such a scandalous scene, to share my latest thoughts with a spirit that would understand. A young man with a gentle and considerate countenance, who had remained almost motionless in the midst of the tumult, seemed to me more likely than any other to answer my questions. I had heard him, a few moments before, ask one of his neighbours for my name, in remarkable terms.

“Who” he said “is this gentleman with the swarthy complexion, the look of a comet, the mobile mouth, the rapid gesture? He is a stranger here, where is he from? Who introduced him? Just now he invited a young lady to dance, and she trembled as she accepted him. He has the looks of a Mephistopheles.”

“I know him not” was all the answer he got. A quarter of an hour later, I approached this inquisitive person.

“Pardon me, sir, for interrupting your meditations; but for some sorts of information I prefer to address youth rather than age. The eyes of an adolescent see better than eyes behind spectacles and also, when I see you there, so calm after such an unseemly disturbance, I think that you will explain to me the cause of a quarrel which was surprisingly not prevented.”

“Your name?”

“Arago.”

“Arago. Are you brother of the famous one?”

“It is I who am the famous one.!

“You are very young.”

“Thank you for the compliment, for my brother and for myself”

“Seriously, is it you who have traveled so much?”

“Seriously, it is I.”

“What is the most peculiar country on earth?”

“Judged by its inhabitants, France. When entering here, I saw only kindly faces, I heard only words of friendship, but already, after barely an hour, there are quarrels, fights, and the most outrageous insults are flying about.”

“It is clear that you have come here from the far side of the world. It is not the quarrel that should most astonish you but the calm and gaiety of the ladies who have witnessed it. See; they are dancing, they are chatting. Do not forget the young person who accepted your invitation, Go skip with her, for she is searching for you with her eyes, in spite of the fear your wild face inspires in her. Afterwards, come and join me and we will talk.”

“So, I do not frighten you?”

“I do not think so.”

“So much the better; for, on the word of an honest man, I have not yet eaten either a small boy or a little girl.”

“Will I not answer for it? “

The contradance was madly gay. I may say, without boasting, that Mademoiselle D. expressed some regret at having been too severe with me and I, entranced, congratulated myself in an undertone on having left behind all the wild women of the steppes of the Americas and the archipelagos of the South Seas.

My young blond boy was waiting for me, smiling.

” Come, come,” he said to me, ” you are adapting very well to our customs. I would wager that a moment ago you had forgotten the scene that moved you so much. I see with pleasure that you are more approachable than your severe looks would lead one to suppose, and now that you seem to me to be from my country and of my time, if you are disposed to listen to me, I can provide you with some information that you may later make use of at your leisure.”

I accepted.

I will not tell you, you who haunt the salons of high society, the general tenor of the vast panorama that unrolled before my eyes. A young dandy, whose tasteful attire I admired, owed all of his merit to a tailor to whom, in order to obtain credit, he had gone in a cabriolet, and the cabriolet had been hired by a liveried servant who was, however, a friend, and not the valet, of the master, who would, in his turn and in another district, put on the livery to enhance the appearance of his accomplice. “I would not be surprised”, continued my young blond, “if the man we are talking about had not come to an agreement with the cardsharp who has just been chased away. He lost heavily and yet he is still cheerful. I would wager that he is at least a third partner in the shameful speculations which so happily ruin so many trusting provincials.”

“If so, then, it is your duty to warn that beauty to whom he is at this moment addressing his flattery. It would be a service to the mother, who seems so complaisant. Do it at once.”

“Return to your Polynesia, traveler, and let me finish. That young woman, in whom you are taking such a lively interest, is the widow of a captain who died young at the siege of Tarragona. She accompanied her husband on his perilous campaigns. In the regiment, everyone called her mademoiselle, without the husband objecting, and, as you know, if you know anything, the archives of all the cities of Spain were burned during our first invasion, and the marriage contract of this dear young lady was destroyed. Her future prospects suffered a little, but hope lives always on in the heart of a pretty girl. She anticipates better days; and, protected by her looks and the strictness of her principles, she is setting about things in the right way.”

“What you are telling me is a little perplexing.”

“I do not want to teach you any more. Ask your brother if you want to extract light from darkness. I can do no more than physics, and I have been as exact as it is”

“My faith, let them sort it out”

“Excellent, my friend; you are becoming civilized. Never meddle in the affairs of cavaliers, unless you wish to get entangled in their nefarious schemes, from which you would only emerge discredited. Do grocers not always have about them a smell of cinnamon or cloves? Can one not guess a hairdresser from six paces? Cannot even an only slightly refined nose tell, from the foot of the Column, that there is a superb perfume shop towards the middle of the Rue de la Paix?”

“In your opinion, then, one runs some danger in frequenting these fine salons?”

“No, not if you are forewarned and prudent. The gaze of a cavalier glides over so many bodies in motion that not a single particle in your clothes will betray you to the outside world. By observing closely you will gain a little understanding, enough to allow you to avoid danger but not so much as to compromise your reputation. The world despises rogues but laughs at fools and dupes. See to it that no one ever laughs at you. As for contempt, it cannot touch you. Look, observe that tall gentleman with the pale face, whose forehead is furrowed by a great scar? He is a cavalier. He owes his ribbon to a mistake by the Minister of War. His name is Durand; he is 32 years old and lived in Barcelona, dealing in small hardware items. One day he had a fall in his shop, and the corner of a lock scarred his forehead for him. Recovered, and with a few piastres acquired by his business, he returned home after our tragic war in Spain. He had barely settled down when an enormous package arrived from Paris.

“Sir, I hasten to send you the croix d’honneur granted by His Majesty on account of your bravery at Figueres. Signed THE MINISTER, etc.”

“The honour was accepted; the decoration shone in his buttonhole; and the brave Durand, who died in Perpignan during the retreat of our armies, who was from the same town as the merchant and was the one for whom the reward was intended, could not lay claim against the imposter. Will you go and undeceive the minister? What does it matter to you that this individual has usurped the reward of one who is dead? Let him strut about with his ribbon and his star. Dear God! Life is really sweet only for those who care little about others. In our country, sir, the man who is most honest is the one who is most skilled at hiding the fact that he is not. Please do not frown so much. A few exceptions will support the general rule, and I am surprised to the highest degree that you, whose adventurous life and ardent passions (for I know you by reputation) have taken you to so many places, I am surprised, I say, that you are still unaware that the country of illusion is the only one worth inhabiting. Could you not give me some details about the citizens of Calcutta, that city of palaces, as the English call it? Would you not like to provide me with documents on the customs and the inhabitants of Calcutta, or studies of the Malays or the Chinese who populate some parts of the archipelagos of the South Seas? What have you told us, in your account, of the inhabitants of the Marianas, whom you call thieves, and of the negroes of Africa, and of those of New Holland, and of those of the Friendly Islands, and of the amiable islanders of New Zealand where Europeans are eaten without taking the trouble to season them with any sauce? Come, cosmopolitan, in what country would you like to live, in this world that is nine thousand leagues in circumference? Do you demand that, for you, the sky will be always blue, women always pretty and loving? That you, a moralist, be given a heart always open to tender feelings, always open to the sweet emotions of the soul? Have you found Eldorado in your distant excursions? Why did you leave? Our old Europe will hurt you; we do not yet eat human flesh, but that will come with civilization. Return to your antipodes.”

I was stunned by this flow of words, through which shone so many truths.

“If life,” continued my young optimist, “is what one makes of it, rather than in the life of those around us, let us try to make it honourable according to our custom and laws, let us never have a serious quarrel with our conscience, and let us laugh at the world’s failings. To seek to correct them is to make trouble for oneself. You are now aware of the ways of examining men and things, now observe only and the lesson will not be lost. Farewell. I can see from here certain movements which bother me, which annoy me; I need some peace and quiet, leave me alone.”

I had hardly left him when the grandly decorated hardware merchant elbowed me, making excuses, and the conversation began.

“You were talking just now to a young man who can give you useful advice, if he speaks differently from the way he acts.”

“You surprise me.”

“He has just been released from Sainte-Pélagie, where he has been for three years.

“Who released him?”

“One of his friends, the very one whose odious conduct so scandalized you an hour ago, the cavalier who was so shamefully chased away. It would take too long to tell you the details, but observe him, study his movements. While waiting to take a leading role, he is already a player. To conceal his strategy, he makes imperceptible signals to a comrade, and since his delight is to fight for himself and his comrades, few people dare tell him what’s what. I am leaving.”

Our explanation was short. The young moralist smiled as he looked at me, and said to me, as he left the salon,

“You would have done better to keep quiet; I’m leaving because I’m expected elsewhere. Don’t abandon these brilliant gatherings; believe me, one can have fun here. The finest salons in Paris have their cavaliers, who are considered as neither more nor less than the most respectable of men. More than ten thousand of them live grandly in Paris without possessing any other fortune. They have cabriolets, horses, liveried valets and mistresses: from where do you want them to obtain the means to maintain their places in society, if not from the houses of bankers and ministers? Among their own kind they would achieve nothing; out in the moral world they can work more safely and with more profit. I saw more than fifty of them at a grand party organized by M. Chateaubriand, and if tomorrow you come to the Rothschild’s I will show you twenty of the most outstanding. Goodbye.”

I barely heard the last words of this shameless youth. He left, casting on me a look of pity and greeting with a kind smile two or three charming people who returned his farewell in the most affectionate manner.

Doubtless the social vice that I wish to condemn is not everywhere as widespread as it is in the salons through which I have just taken you, but our time is the most abundant in men who live at the expense of credulity and good faith. What, in fact, is a cavalier? He is one who profits from the industry of others. The vices of governments alone are the sources of the vices of individuals. If you climb high, and find, in elevated areas, the faults I identify, you will encounter them, multiplied to infinity, as you descend. In the midst of the political events of which we have been the playthings, it is difficult to know exactly by which path arrived this or that individual who dominates us. If he cannot admit all the steps of his career, prejudices pursue him and reach him. In hatred of the men who persecute or humiliate him, he seeks to justify the feelings he inspires, and he easily arrives at his goal. Not daring to become a thief on the high road, because the laws are strong against certain crimes, he adorns the shame with which he covers himself with a brilliant varnish, and lives peacefully among us. The fraudster is therefore a thief and a coward, a thief all the more to be feared because instead of demanding your purse or the life, he robs you with a smile and seems to be protecting you even as he swindles you.

And if I wanted to rise to a higher morality, if I told you of the burning tears that this inconstant race causes to flow, the prisons where it buries its thousand victims, the catastrophic injuries it has caused, if I climbed another rung, and showed the cavaliers seizing the highest positions, monopolizing honours, dignities, titles, and often governing princes and the state at their pleasure, oh then there would be bitterness in my stories, harshness in my pen; for here evil has many more consequences than the regrets of a young man, or a few tears of a father, or one more convict in the penal colonies of Toulon and Rochefort.

I spare you this, you whom I could destroy, you who are condemned to read me.

So the leprosy of the cavaliers is felt in all classes of society, from the small-time beggar who groans as soon as he sees someone approachr him, and who then laughs at the pity he inspires, to today’s men of power, who place their influence at the service of baseness and mediocrity. The cavalier has many disguises, he shows himself in many forms. Sometimes his speech is high and brief, more often humble and flattering. By what signs can we recognize him? By what means can we escape him? He is everywhere. Live at home, alone, without a friend, without a courtier, without a wife, without a servant. Be the most unhappy of men.