Isidore Duperrey joined the Uranie in Toulon as an enseigne, and it was not until March 1821, four months after the expedition had returned to France, that he was promoted lieutenant de vaisseau. He had, however, been effectively the ship’s second officer for more than half the voyage, following the death of lieutenant Jean-Jacques Labiche, and also of his fellow enseigne Théodore Laborde, and his abilities were evidently recognised because, as no more than a lieutenant himself, he left France the following year in command of the corvette Coquille, to continue the work that de Freycinet had begun. With him went several of those who had sailed with the Uranie and had returned on the Physicienne. They included Auguste Bérard, who had been promoted enseigne while on the Uranie, and the master-gunner Rolland, who had been a tower of strength during the time of their marooning in Berkeley Sound.

There was at least one other, and one who might not, from the various descriptions of the Uranie voyage, have been expected to be there. This was the captain’s secretary, Gabert, who would have celebrated his twentieth birthday just ten days after the Uranie left Toulon. When he is mentioned at all In its chronicles, he cuts a slightly pathetic figure, and even the name under which he appears seems to be slightly incorrect; on p. 477 of Gaimard’s diary he is listed as ‘Gabert, Paul-André, secrétaire du Commandant’, and this is the name given in the lists presented by Louis de Freycinet and Jacques Arago, but in the accounts of Duperrey’s voyage and in the pension records of the navy he is André-Paul. For Rose, he was simply her husband’s secretary, who dined with them. It was a privilege that was not without its disadvantages; the food may have been better, but the society was very limited and probably quite intimidating. And, when he did take part in the excursions on shore, he seems to have been perennially unlucky. His first appearance in Gaimard’s diary was during an excursion to Table Mountain.

M. Gabert, who had come with us, stopped at the foot of the mountain; the fatigue he was already experiencing prevented him from continuing (Gaimard, Diary, p.191).

Perhaps this was not such a bad decision on Gabert’s part, because those of his companions who continued up the mountain did so in thick mist and continual rain, and the hoped for spectacular views never materialised.

The second excursion in which Gabert took part was in Shark Bay in Western Australia, and it was nearly the death of him. He and Gaimard managed to lose themselves in the interior of the Peron Peninsula while trying to make contact with its inhabitants, and spent two days and nights without food or water, freezing by night and roasting by day. They would certainly not have survived another day. During their trek back to the camp, there was in interesting exchange between the two, recorded by Louis de Freycinet but omitted by Gaimard from his diary.

With the hope of seeing our ship growing ever fainter, M. Gabert cried out from time to time,

“Why ever did I follow you?’ …. What a terrible idea it was of mine, to decide to follow you! …. Ah! If only the captain had refused me permission to come with you! … .;

“And if also”, I said, laughing “he had had the disgraceful idea of accompanying his refusal with a sound kicking!”

“Yes, certainly, I would have liked that; I wish to God that he had done it! “… he replied seriously.

This singular echo, in the deserts of New Holland, of the “Que diable allait-il faire dans cette galère”” seemed more poignant than it does in the scene by Molière, since it belonged to a drama in which we ourselves were taking part and the outcome of which M. Gabert was contemplating with quite understandable regret. (de Freycinet, Historique, Vol 1, pp. 465-466)

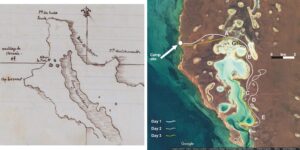

Left: Gaimard’s sketch map og the northern end of the Peron Peninsula. Right: Goggle Earth image showing the approximate path taken by Gaimard and Gabert during their three days of wandering.

There is no record of Gabert having joined in on any of the other excursions, but perhaps he was being kept too busy. He was one of the few people on board who spoke Spanish, and would have been much in demand as an interpreter on Guam, although his efforts were not always applauded. Commenting on his work on some documents concerning the marriage customs of the Chamorros, Gaimard wrote:

This translation by M. Gabert could have been more elegant; it could, above all, have been more succinct. (Gaimard, Diary, pp. 421-422).

It was, however, left to Gaimard’s superior, Jean-René Quoy, to provide an insight into what it must have been like being secretary to Louis de Freycinet.

The following story illustrates [de Freycinet] perfectly: on the Uranie he had a secretary, but this was not always sufficient and he also employed the chief steersman who, in his picturesque Provençal speech, told us how things were going between them: “The captain” he laughed, “makes me write three lines and crosses out two. He dictates five more to me, then erases everything; so that after an hour of work, we are, tronn-de-lère! in front of a paze of erased words, and have to start all over again (Quoy, Mémoires, BSGR 38, pp. 165–6).

This certainly suggests that Gabert may have been more fully occupied, for more of the time, both whilst at sea and during the relâches, than anyone else on board. However, his bad luck followed him, even if he did avoid excursion into hinterlands after his experience on the Peron Peninsula. Whilst the Uranie was anchored off Rawak, Rose de Freycinet rejected the water supply on the island and sent her laundry to be washed at a source on the neighbouring, much larger, island of Waigeo. Disaster followed.

On the 26th, the Canot du Commandant was cast ashore while on its way to the watering place and quite badly damaged: M. de Freycinet lost some of his table linen and M. Gabert a good number of shirts. (Gaimard, Diary, p. 344).

Tactfully, Gaimard makes no mention of any items of clothing that Rose might have lost, but she, in the twelfth of the letters she wrote to her mother, contemporary copies of which are now preserved in the Mitchell Library in Sydney, makes it clear that the Freycinet losses amounted to considerably more than a few items of table linen. This may, moreover, not have been the end of the depletion of Gabert’s wardrobe thanks to the carelessness of his employers, because in the fourteenth of the letters, Rose wrote that:

….. four days ago, when we woke up in the morning, we learned that during the night, our silverware, table linen, the clothes of our servants and other effects had been stolen from the ground floor of the house we occupy. (Rose de Freycinet, Letter 14).

Gabert may not have been amongst the ‘servants’ who sustained these losses, but, given his habitual bad luck, one can imagine that he might have been.

All this would have been enough to put most secretaries off from ever going to sea again, but Gabert was evidently made of sterner stuff. Less than two years after his return to France he was on board Duperrey’s Coquille, committed to a second circumnavigation, and If the accounts of that voyage are to be believed, he had not only been allocated much greater responsibilities but had matured considerably. He even merited an individual mention in the brief ‘Rapport fait à l’Académie des Sciences’ that forms an introduction to the first volume of the Partie Historique of Duperrey’s own, and never to be completed, Voyage autour du Monde.

We owe to M. Gabert, agent comptable, to whom European languages have become familiar, interesting information on the state of trade and industry in the colonies visited by the Coquille. (Duperrey, Partie Historique, p. xliv)

The two words underlined are conventionally translated as ‘accountant’, which is not a nautical term but it was the savants of the Académie doing the writing. Their usage is repeated where Gabert is first mentioned in the main text,

MM. Garnot and Lesson combined their efforts to treat all the other branches of natural history. M. Gabert, agent comptable and interpreter of the expedition, undertook the collection of information on the state of commerce and industry of the peoples we were to visit. (Duperrey, Partie Historique, p. 7).

Where, however, Gabert first appears in person in the text, in the Brazilian port of Santa Caterina which was, at the time, uncertain as to whether it would join the newly independent Brazil or strike out on its own, he is given a naval title:

So, the next day, M. Jacquinot was sent early to the commandant of the fort of Santa-Cruz, and with him M. Gabert, commis aux revues, to serve as his interpreter. (Duperrey, Partie Historique, p. 44).

The underlining is my own; the title shows that Gabert’s responsibilities on the Coquille were very much greater that those he had on the Uranie, and that purser is indeed a suitable translation. He would have been responsible for making payments ashore, and for keeping track of the accounts and the depletion of the stores when afloat. There is no evidence of his having been able to speak Portuguese when on the Uranie, but by the time he was on the Coquille he was evidently competent in that language as well as Spanish.

The visit to Santa Caterina was not a great success, as the next few pages of the Partie Historique demonstrate. Gabert might even have found himself regretting the life-threatening simplicities of the Peron Peninsula.

Desiring to have reliable information on the events that had been described to us, we decided to send several officers to the city of Nossa Senhora do Desterro, capital of the province of Santa-Catharina. M. d’Urville undertook to inform the governor of the arrival of the corvette and the reasons for its visit; he was accompanied by MM. de Blosseville, Gabert and Garnot.

They were not long in acquiring a detailed understanding of the circumstances that had caused Brazil’s declaration of the independence, and they learned that the government of the province was entrusted to a provisional junta composed of five members, who were assembled at the time of their arrival. They were conducted there by a captain of infantry, who himself introduced them into the room where the junta held its meetings. M. Gabert explained the object of our relâche to the president, and M. d’Urville at the same time presented the letter of the King of Portugal, which commanded all states subject to his crown to assist us.

M. Gabert was then introduced to the leading merchants of the town, among whom he had been instructed to find a supplier of fresh provisions for the crew, but he found them very unwilling, and that it would be really impossible to obtain any supplies, because they had hastened to send their funds to Rio de Janeiro for greater safety during the events that were about to take place: he learned, moreover, that bills of exchange are not generally accepted in this country, which is impoverished and where commerce is very limited. M. Gabert then withdrew, convinced of the impossibility of obtaining resupply for drafts, and went back to the beach, the place appointed for the return on board. (Duperrey, Partie Historique, pp. 46-48).

Unsatisfactory, no doubt, but at least he had done his best, and help was at hand. The élève de la marine Jules de Blosseville takes up the story.

“As we approached the canoe,” said M. de Blosseville, “we were invited to enter a house very pleasantly situated and where wide views unfolded before our eyes. There we were received by Dom Jose Pinto, the port captain, already known from the voyages of Captain Kotzebue, with an honesty and a cordiality that we had despaired of finding at Santa Catharina. He soon invited us to go into an apartment where an elegant meal was served. We could talk only in English, the conversation revolving around the Russian navigator, his expedition and ours. MM. d’Urville, Garnot and Gabert joined us there, and we embarked at four o’clock to return on board; we went there directly, favoured by a gentle breeze, the evening being too late to touch the Isla de Ratones, as we had intended.” (Duperrey, Partie Historique, pp.48).

Presumably the supply problem was solved with the aid of the port captain, because the Coquille remained long enough in Santa Caterina for a full suite of measurements to be made before departing for Cape Horn via the Falklands and, for Duperrey, Bérard and Gabert at least, a bitter-sweet trip down memory lane. Once round the Horn it was Spanish colonies that they visited, and these were also in a state of revolt. In Chile a second revolution was under way with the aim of ejecting from power the father of the first revolution, Bernardo O’Higgins. Again, it fell to Gabert to conduct the negotiations for obtaining more supplies.

Just as in Santa Catharina we had witnessed the declaration of Brazilian independence, here we witnessed the revolution which brought about the downfall of the Supreme Director, Don Bernardo O’Higgins. On learning of the meeting of the troops which were to march against him, we feared that the preparations for this expedition would make it impossible for us to replace the three months’ worth of provisions that we needed to follow the plans we had drawn up for ourselves. We hastened to send MM. Bérard and Gabert to the city of La Concepcion, to General Ramon Freire y Serrano, governor of the southern provinces of Chile, under whose influence the uprising against O’Higgins was being prepared, to inform him of the object of our mission and the purpose of our relâche. (Duperrey, Partie Historique, pp. 134).

Things went well, despite the political upheavals that were taking place ashore, and it seems that Gabert had at some stage added horsemanship to his other accomplishments.

On the first of February, General Freire sent us an orderly sergeant with several horses to take us to the town of La Concepcion, where he was expecting us to dine. The desire we had to take advantage of the little time we wanted to devote to this relâche had made us postpone until this day the visit we owed him. We left with M. Gabert early in the morning. Our horses had barely left Talcahuano than they began to gallop, and took us to the town necessarily at this speed, for they always showed themselves recalcitrant when we made them change pace or wanted them to stop. The Chilean horseman who accompanied us told us that the country’s horses were trained in this way, and that galloping was their ordinary gait as soon as they had a path to travel outside the walls. Little care is taken of these useful animals, accustomed to running errands of thirty to forty leagues a day. (Duperrey, Partie Historique, pp. 138).

After this excitement, Gabert made just one more appearance in the report, but it was a significant one.

General Freire, driven either by love of his native country, or by ambition, agreed to serve in a cause that was bound to result in civil war or the fall of O’Higgins, his protector, his brother in arms. The people were called upon to elect their deputies for the formation of the assembly which was to regulate these great interests. The inhabitants of the province of Coquimbo, at the instigation of the Penquistos, followed this example. One will be able to see in the following authentic documents the detailed motives of this revolution, and to form at the same time an idea of the spirit and the capacity of the Chilean legislators: the originals were given to M. Gabert, to whom we owe the translation. (Duperrey, Partie Historique, pp. 183).

This is, in fact, the last paragraph of Duperrey’s text in this, the first and only volume of the Partie Historique to have been published, which takes us no further than South America. The paragraph is followed immediately by Gabert’s translation of the Chilean documents, which takes us to the end of the volume on Page 202.

After the return of the Coquille Gabert recedes into the twilight, but he did produce his own brief account of the voyage, as noted in the catalogue of the Turnbull Library. which lists a ‘Précis de la campagne de la corvette de S M la Coquille‘ by Gabert, André-Paul. Included in the note is a reference ‘AN Marine 5JJ.82’, denoting the marine section of the Archives Nationales, and following this clue leads to a listing of the contents of Folders 5JJ. 80A to 87B as relating to the voyage of the Coquille, but that is as far as things can be taken without a visit to Paris. His life thereafter is summarised in the pension records of the French state.

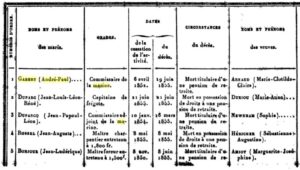

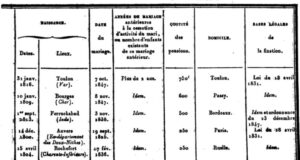

Extract from the Bulletin des lois de la République Française, Volume 2; Volume 6, showing Paul-André Gabert as a pensioner. The entry was presumably made in order that his widow would continue to receive a pension, since his own death date is shown.