In Letter 13 in the collection of copies of letters written by Rose de Freycinet to her mother which is held by the Mitchell Library, she noted that the governor of Guam, Don José de Medinilla y Pineda, had been at Umata (now Humåtak) when the Uranie arrived. He had come because of the presence there of a Spanish vessel, the La Paz that had arrived a few days earlier, and he was there not just to greet her but to satisfy himself that she was not in unfriendly hands. It was a well-founded fear, because, as Louis de Freycinet wrote on p. 226 of the second volume of the Historique, the narrative section of hisVoyage autour du Monde:

That same year the frigate Argentina, belonging to the insurgents in Spanish America, and commanded by a French officer named Hippolyte Bouchard, was patrolling the seas between Manila and the Marianas. Don Medinilla had been warned by the governor of the Philippines to be on the lookout for this vessel, which attempted to enter Spanish ports under the flag of that nation, saying that it had been sent by the king to make scientific discoveries, but in fact with the aim of looting the royal treasury and forcing contributions from the inhabitants. To avoid falling into this trap, Don Medinilla speedily implemented all the precautions he thought necessary for the safety of the colony he governed, and lookouts were posted on the principal heights to warn of the approach of suspicious vessels. But if this vigilant governor preserved Guam from all surprise, he could not save his own personal brigantine, which, being then at sea, was captured near the Philippines by this enemy vessel.

The context suggests that ‘the same year’ was 1817, but in fact the brigantine was captured in April 1818, and Bouchard’s semi-piratical cruise (he was operating under letters of marque from the government in Buenos Aires), was over.by the time the Uranie arrived off Guam a year later, Having spent much of late 1818 and early 1819 harrying the coasts of Spanish California, he had sailed south to take part in the liberation of Peru. In the extract quoted, the ambiguous ‘that nation’ whose flag he flew when it suited him may have been either that of France, or Spain. There is, however, no other evidence of his claiming to be engaged in a mission so similar to that of the Uranie, which was still in Rio at the time, and this may be a flight of imagination on the part of de Freycinet, bolstered by the fact that Bouchard’s predations did have one minor impact on members of the Uranie expedition. When Bérard, Gaudichaud and Arago accompanied a Carolinian fleet to the northern Marianas, their arrival off Rota caused some degree of panic, and In the Historique, de Freycinet quotes Bérard’s account of their reception.

The shot I fired had spread alarm throughout the island: the women fled towards the hills; the men armed themselves as best they could, and it was even said that some had argued for immediate surrender, since there was no hope of resisting enemies armed with firearms. These fears were to some extent justified by letters received from Guam prior to our arrival, which said: “The corvette anchored at the port of San Luis is not French, as has been suggested, but carries insurgents from Spanish America; she is waiting for a second ship, in order to seize Guam. Everyone is convinced of this; the governor is the only person who believes these foreigners to be honest people. In the meantime, their commander is sending three officers, whom you will see on Rota, to visit the northern islands [Historique, v.2, p. 159].

Bouchard’s life was a remarkably active one. Born on the French Riviera, he had a varied career in France’s navy and merchant marine but in 1809, disillusioned with the transformation of revolutionary France into an empire, he travelled to Buenos Aires to join the rebels there. After taking part in a series of battles, both onshore and afloat, he left on the 9th of July 1817 in command of the frigate La Argentina, intending to prey on the Spanish – Philippines trade. He took the eastbound route, and after an incident-packed voyage, was off Manila by the end of January 1818. The city itself (the present-day Intramuros district) was too strongly fortified to be attacked directly, but Bouchard instituted a highly effective blockade that lasted, with some interruptions, until mid-April, when the prevalence of scurvy amongst his crews forced him to leave the area. He then set sail for Hawaii, which he reached on the 17th of August 1818. One consequence of his stay there was reported by Louis de Freycinet, who wrote that when he visited Maui, he was …

….. met on the shore an Anglo-American named Butler, who later confessed to me that he was a sort of consular agent of the government of the United Provinces of South America, and that he held his powers from the same commander of the frigate Argentine, who, recently cruising off Manila, had captured the brigantine of our friend Medinilla, governor of the Marianas.[Louis de Freycinet, Voyage autour du Monde: Historique, v.3, p.542]

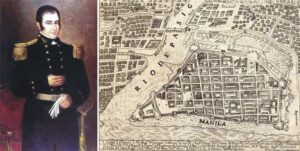

Left: Hippolyte Bouchard. Painting in oils by José Gil de Castro, date unknown. Right: Manila, the Intramuros. The map, from the Malaspina Expedition, which visited the city in 1792, shows a city of stone houses, churches and palaces surrounded by a strong stone wall and guarded by a fort at the river mouth.

This is interesting, because according to Alejandro and Mariana Rossi Belgrano, after obtaining supplies on Maui, Bouchard went to Oahu, and met Francisco de Paula y Marín and appointed him as a representative of the United Provinces of South America. Have these two people, both foreigners settled on the islands, been confused, or did Bouchard appoint representatives on both islands? We know that he had been first to the Hawaii itself, the ‘Big Island’, where he met Kamehameha, the newly established king of all the islands, because he obtained from him an Argentinian frigate or corvette, the Santa Rosa, which had been sold there by its crew, who had mutinied. The king claimed to have paid 600 hundredweight of sandalwood for her, but handed her over to Bouchard in exchange for his sword, his commander’s hat, and the award of the title of Lieutenant Colonel of the United Provinces. Bouchard was, it seems, a much more accomplished negotiator than de Freycinet who, when dealing with Kamehameha’s son and successor, received only a wooden spear in exchange for his sword.

But what of Medinilla’s brigantine? That is a story in its own right. In early April 1818 Bouchard was still off the west coast of the Philippines when he sighted the vessel and gave chase. She escaped into the Pasig River, by-passing Manila to take refuge a short distance upstream in the port serving what is now the central city district of Santa Cruz. Bouchard was unable to follow her into the shallow water, so he sent three boats to capture her, led by a cutter, which arrived first. Her captain decided to attack without waiting for the others, and his ship was overturned when the crew of the brigantine threw ropes around her masts. Fourteen of the assault party were shot and killed in the water, the others being rescued by the other two boats, which then retreated. In a second attempt they found the brigantine had been abandoned, and it was added to Bouchard’s small fleet of captured vessels. What happened to her after that is not known, but one thing is certain.

Medinilla never saw her again.