The route chosen by Louis de Freycinet through the Western Pacific took the Uranie into the geographic centre of the archipelago of the Carolines. He did not stop, but passed sufficiently close to the isolated island of Pulusuk and, on the following day, to the islands of the Poluwat and Pulap atolls, to trade with the islanders. They came out to meet the Uranie in their outrigger proas and had no trouble keeping up with her whilst the bargaining was completed to everyone’s satisfaction. Every one of the diarists was impressed by the Carolinians, and these first impressions were reinforced on Guam when they met a group from Satawal, an isolated ‘low’ (but by Carolinian standards large – 1.3 sq km) island located some 75 km east of the Lamotrek atoll and 300 km west of the path taken by the Uranie. The islanders were on their way to visit their very recently established settlement on Saipan and took Bérard, Arago and Gaudichaud with them as far as Tinian, collecting them on their return a few days later. Thanks to these contacts and the extensive studies of the central Carolines already made by Don Luis de Torres, the Uranie expedition was able to bring back to Europe a considerable amount of information about a people whose home islands they had seen only in passing. It including information on linguistics, a secondary field of study for the voyage and the subject of the final and never-to-be completed volume of Louis de Freycinet’s massive ‘Voyage autour du Monde’.

Figure 1.The route of the Uranie from south to north through the Caroline Islands. The northern segment of the track is pointing directly towards Guam, still 800 km away. The modern boundary in the Federated States of Micronesia between Yap and Chuuk states runs runs approximately along the 144th East meridian but this does no reflect cultural realities.

Even today there is very little information easily available about the languages of the Carolines. An undated word listed designed for use by medics visiting Chuuk was found on the website of the Universityof Hawaii’s Center for Pacific Islands Studies but could but be re-accessed and there is also a wide-ranging but very incomplete multilingual word list on a site of the Micronesian Comparative Dictionary, which appears to have been compiled by specialists mainly interested in reconstructing the proto-Micronesian language. As far as can be determined from an Internet search, the two main indigenous languages of the Carolines, Chuukese and Ponapean, are comparatively healthy, with several tens of thousands of speakers each, but the language of the third of the three ‘high’ islands, Kosrae is considered threatened, with fewer than ten thousand speakers. Other Carolinian languages listed on the site of the Endangered Languages Project include Ulithian (3075 speakers), Woleian (1650), Satawalen (400), Puluwatese (1360) and a language simply known as ‘Carolinian’ spoken on Saipan. This last must surely be the language spoken by the descendants of those settlers from Satawal who were just installing themselves on Saipan when the Uranie visited Guam.

Because of de Freycinet’s failure to complete his ‘Linguistics’ volume, the diary kept by the assistant surgeon and naturalist Joseph-Paul Gaimard is one of the principal surviving records of the expedition’s linguistic studies. On p. 408-409 Gaimard set out what he called a “Petit vocabulaire de l’Ile de Lamursec”, and followed that , on pp. 442 – 452, with a much more comprehensive “Vocabulaire des Iles Carolines”. Unfortunately, he gave no details as regards his sources. The first list, from ‘Lamursec’, may have been compiled from his own interactions with the islanders from Satuwal, considered to be part of the same polity; the second and much longer list certainly includes words copied directly from documents prepared by Don Luis de Torres and may have been obtained entirely in this way. Don Luis was a major source for what Gaimard was able to say about the Chamorro language of Guam, and had himself visited Woleia, about 250 km west of Lamotrek. What he wrote down was probably essentially Woleian.

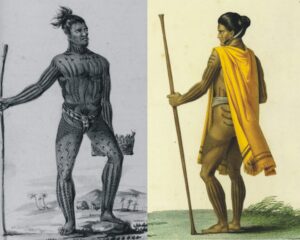

Figure 2. Left : The ‘beautiful tatoo’ of Puluwat. Marginal drawing by Jacques Arago in Gaimard’s diary, p380. Right : The Satawal aristocrat behind the settlement on Saipan, as drawn by Jacques Arago. Reproduced with permission. Library of Guam.

Culturally, the inhabitants of the eastern reaches of what is now Yap State, one of the four Federated States of Micronesia, have today much more in common with their neighbours in the western part of Chuuk State than they do with the people of Yap itself, and it is probable that this comment could have been made with even greater force in the early 1800s. The drawings made by Arago of members of the ‘navigator’ aristocracy of Puluwat and Satawal show almost identical tattoos, and notes made by Gaimard from his conversations with Don Luis document the very direct links between Lamotrek and Woleia. Despite the distances involved, there was clearly much coming and going between the islands, and their languages, or dialects, would be expected to be very similar also. Despite this, where they overlap the two vocabularies provided by Gaimard show major differences, even in such basic matters as the naming of the numerals.

English ‘Lamursec’ ‘Carolin’

head malec rouméï, roumaï; simoié

hair laneremuy alourméï; alérouméï; timoé

forehead nooy manhoï

eyebrows fati satou; fatal; fateul; fati

eye vetay métal; metaï; messaï

nose poti poiti; poitīnĕ; poitil; podi

mouth colog e-houai

tooth ñguy ni; gni; ni-i

lip tulivay tilouéï; tilouel; tiliaoual; alisséōu

cheek tepay tepal; aïssapal; aouss-pai

beard atey alouzai; alissel

ear taligui rapélépréï; rapélépéréï; oufoi

nape oguey lougourounhéï; lougoulouhouel; lougoul-houéï

chest obouy loupaï; oupoual; oupouéï; oiti

belly sacay ségaï; oubouoï

umbilicus pusey pouzéï; poujé; pougoi-ie

shoulder efaray evaraï; avaraï; efaraï

right arm pay copay rapélépéï; chapélépéï; gapilépeï

left arm pay mongay rapélépéï; chapélépéï; gapilépeï

elbow apit rapélépéï; apélépélépéï

hand paramdemert galéïma; pranéma; pralémal; pélalipéï

thumb atelipai catoulēppèné; catoulépal

backside pulove louĕtti

buttock safilafi pourouéï; pouroul; palipaliaouati

thigh ofoy rapélépréï; rapélépéréï; oufoi

knee pugoy pougouéï; pougoué

leg perai braléparéï

foot para parra perray paraparépréï; paraparalépéréï; pérapéral

nail cuyi coul; cuï

man mal mal; marr; mérer

woman fayfil rabout; faifid

child sariquit sari; tarimar; oligat

little child sariquit sarikid

water (drinking) curuc rall; ralou; ralu

sea toad tātti; amorouc

coconut tree liac roau

coconut roo tohōhō; rō; cho-o

coconut shell tagac maribirip

hen maluc moa; maluk; baluk

sun alo alet; yal

cloud yaan sarōnnĕ; ieng; iengué; maniling

night bòn poum

1 yot iot; hiot[1]

2 ruec ru; rou; ru

3 eli Iel; Iēli; iol; hiel

4 san fan; fel; fang

5 lima līmmĕ; lībĕ; nīmmĕ; lim

6 golo hol; hol

7 fia fiz; fus; fis

8 guali oual; ouānĕ; ouhānĕ; hual

9 tiva tihou; tihu

10 seic sèk; sièkĕ; seg

11 yota seg-macéōū; seg-maceo

20 ruic ruèk; mentéruèkĕ; rouek; ruheg

30 senic sérik; sélik; élig

40 faic fahik

50 limil limèk; némèkĕ

60 goloec holik; oulik; oulèk

70 fiov fizik

80 gualic oualik

90 tiguic tihouèkĕ

100 sebuc siapogou; siapougou; iapougou

200 reupud rouapougou

300 felepud iélépougou; élépougou; sélépougou

400 fapud fapougou

500 limapud limmapougou; nimmapougou

600 golopud houlapougou

700 ficipud fizipougou

800 gualipud oualépougou

900 tivapud touapougou

1000 sangres sānrēssĕ;cenrēssĕ; zellé

2000 ruangres ruanrēssĕ

No doubt some of the differences between the second and third columns in this tabulation can be attributed to subjective differences in the way sounds were heard by the people who wrote them down. Don Luis had a Spanish father and a Chamorro mother, and if it was indeed Gaimard who first compiled the ‘Lamursec’ vocabulary it is not surprising that differences occur, as they do in various transcriptions, including Gaimard’s. of Chamorro. Not everything, however, can be explained away in this fashion, and it is surprising that the names of such common, and vital, items as drinking water and coconut trees should be so different in the two lists. Another difference is that the words in the third column are often significantly longer than those in the second, even where the basic root is the same in both. Don Luis, brought up speaking Chamorro, would have had a better ear for linguistic complexities but might also have unconsciously added a Chamorro overlay.

One item, however, is strikingly similar in both lists and far beyond. The word ‘lima’, five, does not only, in its essentials, occur in both, but also in Malay, Indonesian, Chamorro, Tagalog (Filipino) and Samoan. That this one numeral, and no other, should be common to such a broad swathe of Malayo-Polynesian languages is impressive but perhaps not surprising. The people who took the word from Asia out into the Pacific did, after all, have five fingers on each hand, and five toes on each foot.