One matter on which Donald Trump, Ayn Rand (and her present day acolytes), and Bezalel Smotrich, Israel’s finance minister and now effectively governor of the occupied territories, seem to be in complete accord is their approach to the future of Palestine. In their eyes it is unnecessary to consider the opinions of the Arabic-speaking half of the population inhabiting the land between the river and the sea.

There are, of course, nuances. For Rand, the Arabs were primitive nomads, undeserving of a share in a land otherwise occupied by people who, while regrettably tending towards Socialism (a phase she would no doubt be gratified to see as over) were ‘the sole beachhead of modern science and civilization on their continent’. For Trump, Arab Palestine is a real-estate opportunity, whose inconvenient occupants can be removed in the interests of high-value luxury development, and who might or might not be allowed back but should certainly have no say in what happens. As for Smotrich, he laid out his plan for the area in a 2017document, written originally in Hebrew, with the English title “Israel’s Decisive Plan”.

The Plan begins with a statement with which many would agree publicly, and many more reluctantly accept in their hearts, which is that the two-state model is dead. There are now more than half a million Israeli settlers in the West Bank. Does anyone really believe that they will ever leave voluntarily, or that the global political scene will change so dramatically that it will be possible for them to be removed by force? It seems equally impossible to remove all two million inhabitants of Gaza, let alone the two and a half million Arabic-speakers living in the West Bank. Smotrich, however, ends his first paragraph by saying ‘there is no room in the Land of Israel for two conflicting national movements’. That also is a fact; a house divided against itself cannot stand, and, thanks to Israeli settlement, that is as true of any imagined state comprising the West Bank and Gaza as of Israel itself. His solution is a single state occupying the entire space ‘between the river and the sea’, within which Jew and Arab would live together in peace. As he noted, with all sorts of qualifications, “the Arabs of the Land of Israel lived for decades in peace under the Jewish regime, and were seldom involved in terrorism or activity against the State of Israel”.

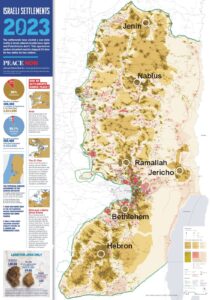

Figure 1. The West Bank, showing the current divisions in the area and the locations of Israeli settlements. The centres of Smotrich’s six ‘municipaliies’ have been added. The areas that each would occupy have not been defined, but the size of the area currently allocated to the Palestinian authority around Jericho is suggestive. Credit: Peace Now.

It is at this point that his ‘plan’ begins to unravel, because the single state he envisages would bear no resemblance to the present Israeli state in its treatment of its Arabic-speaking citizens. In essence, it is for them only in …..

….. a model of residency that includes autonomous self-management including municipal administrations, alongside individual rights and obligations. The Arabs of Judea and Samaria will conduct their daily lives on their own terms via regional municipal administrations lacking national characteristics. Like other local authorities these will hold their own elections, and will maintain regular economic and municipal relations between themselves and authorities of the State of Israel. In time, and contingent on loyalty to the state and its institutions, and on military or national service, models of residency and even citizenship will become available.

He then puts a little more flesh on his plan. For self government, ‘the Arabs of Judea and Samaria will be divided into six municipal governmental regions wherein representatives will be elected in democratic elections: Hebron, Bethlehem, Ramallah, Jericho, Nablus, and Jenin’. They would not, however, be able to vote in elections for the Isaeli Knesset (as Arab-speakers can in today’s Israel ) and, in a key paragraph, he wrote that they would ‘enjoy freedom of movement and the right of entry’ to the rest of the country, but with the proviso that it would be just ‘for work and for humanitarian reasons’.

That, of course, was the situation in Gaza after the withdrawal of the Israeli settlers and before the imposition of the blockades. The Smotrich solution is, it seems, to create six smaller Gazas within an enlarged state of Israel but without Gaza’s access to the sea. Their sizes are not specified, but the map in Figure 1 is suggestive; they would be tiny, and their citizens would consequently have fewer rights, and be more restricted in their movements, than were enjoyed by the citizens of Gaza.

That is not a solution with any hope of stability. Before outlining his plan Smotrich effectively recognised this when he offered this thought.

“Insanity,” states a famous quote often attributed to Albert Einstein, “is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

Even Ayn Rand might envy the smoothness of his transition from reasonable analysis to barking madness.