Will I write to that university, sign this petition, etc? Of course I will, but without the slightest hope that anything I, or anyone else, can do will have the slightest effect. In my experience, once a university administration has decided on a course of action, it is amongst the most immovable of objects, and closing departments and firing staff is what really floats the boats of the assorted provosts, rectors and vice-chancellors. Forget academic excellence and international reputation, since Thatcher’s decision that universities were better run by businessmen than academics, it is the accountant’s bottom line that has been the criterion. Their ideal, one feels, is an institution from which those annoying lecturers, readers and professors have been entirely removed, leaving just the administrative pyramid, topped by a ludicrously over-remunerated figurehead, as all that remains. Today it is the much admired department at Leicester that is scheduled for demolition, but only a few short weeks ago it was the equally highly regarded department at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam.

And yet ….

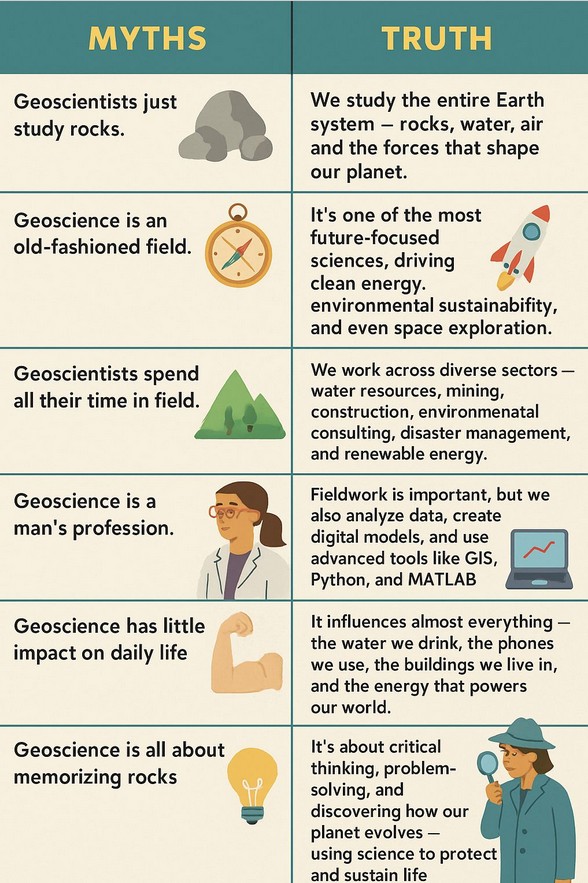

Despised as they are, one has to feel some sympathy for the administrators. The decline in applications for Earth Science courses is undeniable, and where school leavers vote with their feet, university heads will follow with their cheque books. Why, we must ask ourselves, are the degrees that gifted so many of us with exciting, intellectually challenging and reasonably well-paid careers not seen as more attractive? A few weeks ago, Iyetomola Rachael Ojo, a Nigerian who describes herself as a passionate geologist and geophysicist, posted the tableau in Figure 1, in an attempt to answer that question.

Figure 1. Myths and truths

Was she right? Are these really the perceptions that are turning school-leavers away from geoscience? And if they are, are the ‘Truths’ that she suggests as counter to those destructive ‘Myths’ likely to alter the situation, were they to become widely accepted?

Let us consider them, one by one.

It is, of course, true that it is not only rocks that geoscientists study but, let us face it, it is mainly rocks. Do water and air really seem more exciting? Is there really a perception of geology being ‘an old-fashioned field’ and if so, is that what is driving potential students away? According to the Complete Univesity Guide, the ten most popular university courses at the moment in the UK are, in ascending order of popularity, Business Studies, Adult Nursing, Economics, Sociology, Medicine, Design Studies, Sports Science, Computer Sciences, Psychology and, by a massive margin, Law.

Law!

What could be more old-fashioned than Law?

Fieldwork? My own experience suggests that. far from being a negative, this is the thing that drew many, perhaps even most, students to geology. A career tramping the world in big tacky boots was just what they wanted, and a remarkable change occurring during my intermittent spells as a university teacher has been from girls making up perhaps 10% of the class when I began to about 50% by the time I left. All fuelled by the same wish to do fieldwork and a change due, in a great part, to a decline in the number of school teachers who would tell their pupils that geology was not for girls. The sad thing is, how few of those who wanted a career in the great outdoors, whether male or female, actually achieved that aim.

Little impact on daily life? Is that the reason?

In fact, I think the reverse is true. Surely one of the main factors driving school leavers away from geology is the realisation that a career in it would very likely be a career in one of the extractive industries, not only hydrocarbons but mining and quarrying, and these have, not undeservedly, a very bad reputation amongst just the sort of people for whom fieldwork would be an attraction. Is it hopeless to point out that this is a feedback loop, and that the fewer people there are in the upstream end of these industries, upon which humanity’s current way of life depends, who actually care about the environment, the more likely it is that the lawyers and accountants who control many of them will continue to favour profit over sustainabi;ty.

Memorising rocks?

Here,I think. the problem is rather different. As a feature of geology courses, ‘memorising rocks’ dominates most in schools, and my experience suggests that the yearly reduction in the number of sixth-formers opting for Geology A-Levels, while widely deplored, may not be the disaster it is assumed to be. Not only were such students always a minority among the applicants in the universities where I have taught, but they were not necessarily welcomed by my geological colleagues. If they had been well-taught, they found much of the first-year syllabus boring, and if they had been badly taught the battle to get them to unlearn what they thought they knew could be a bitter one. Even the existence of geology at A-Level was a problem, because a significant number of school-leavers, assuming it was an entry requirement, did not even consider university-level geology as a possibility. Seventy years ago, I was myself in that category.

But is not the almost apologetic approach epitomised by Figure 1 in any case, a mistake? Is defeat not being admitted before battle is even joined?

Let us instead accentuate the positive. What should today’s universities be telling potential students?

That a geology degree has so much to offer. More, I would suggest, than almost any other degree. My own degree is in physics, and when I first came in contact with geology at university level, I was blown away by how much more sheer fun there seemed to be in studying geology than there had been in studying physics.

That they will, almost certainly, be in rather small departments by modern university standards, and be part of cohesive groups, all of whose members they will know extraordinarily well by the time they leave, partly because they will have shared with them the rigours and delights of field work.

And, if they do then choose to make a career of geology, it is highly likely that they will encounter some of those same people, scattered through industry and academia, because the numbers overall are quite small. That can be useful..

And, they will have far greater contact with the academic staff than students of most other subjects. There is nothing like seeing your professor up to his knees in muddy water in a Scottish bog to make you realise, as one ex-student told me of one of my colleagues, to make you realise that he or she is also a human being.

And, because of the range of scientific disciplines that are now being brought to bear on geology, they will receive the broadest of broad training in the sciences overall, as well as in the special features that make geology what it is.

And that the broad education it involves is something that will give them value if they choose not to go into geology. One of the greatest needs in the world today is for journalist, politicians, administrators etc. who, while not themselves practising scientists, are educated in science, are scientifically literate.

And that the skills in which they will be trained will include ordinary literacy as well because, having worked in the field, they will be trained in preparing reports on their findings. In a world of increasing reliance on AI, the ability to function without it’s help is becoming, in itself, a marketable skill.

And although it is difficult to predict what the future will hold in that respect, geology may be one of fields of professional employment most resistant to AI-fuelled redundancies. The evidence used to make decisions in geology is never more than partial, and the ability to make reasoned decisions in the face of sometimes very large uncertainties is not something at which AI is likely to excel in their professional lifetimes.

And they will, of course, learn how to use it, and a number of other packages that are now standard tools in the geological world, and how those programs work.

Why would you choose any other degree?

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

But perhaps I have been out of the business too long, and students have changed, and no longer want what we, in our generation, wanted.

I wonder.