Adria, or at least that bit of it positioned near the top of the crustal stack, just got a little bit smaller. At about half past eight local time in the morning of the 9th of November 2022, a Magnitude 5.6 earthquake nucleated at a nominal depth of 10 km beneath the Adriatic sea near Ancona. The shock was felt in Rijeka, although not by me, because I was in the Adriatic at the time, but our next-door-but-one neighbour reported being quite severely shaken.

Figure 1. Epicentre and felt intensity contours of the Marotta earthquake

The depth is nominal because teleseimic methods of determining earthquake depths lack the resolution to define things any better in the uppermost crust. All we know, at present and unless some serious work is done on the records from nearby seismographs, is that the hypocentre was only a few kilometres down.

Figure 2. Moment-tensor solution for the Marotta earthquake

But if teleseismic arrivals are poor at defining very shallow hypocentres, what they can, and in this case have, given us is the nature of the dislocation. It was an almost pure compression, directed almost precisely at right angles to the Italian coast and with focal planes dipping at about 45̎°. Somewhat steeper than that on the west dipping plane and shallower on the east dipping one, and since it was almost certainly the western block that moved over the eastern block it was, technically speaking, a reverse fault rather than a thrust. The western block is the Appenine range and the eastern block is the lost continent of Adria, and it is very well attested that the Appenines are moving east.

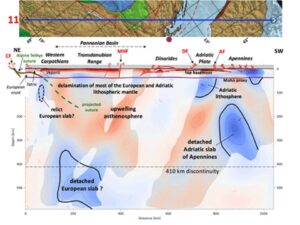

The use of teleseimic waves to study earthquakes has, of course, a very long history, and the methods are becoming increasingly sophisticated. The arrival times are increasingly being used for is the study of deep structure using tomographic techniques, and one recent paper includes a profile that passes very close to the epicentre of the Marotta earthquake. Its authors chose to show their cross-section with west to the right, in defiance of convention, and I, for one, would normally find that hard to work with and would probably reverse it, but in this case the orientation suits me very well. The lower margin of the map part of the illustration passes almost exactly through the Rijeka suburb of Sušak, where I am sitting writing this blog. It is very easy for me to imagine myself looking south towards that section.

Figure 3.Tomographic section running almost through the site of the Marotta earthquake, Figure A12 of Handy, M. R. Schmid, S. M. Paffrath, M. Friederich. W,. 2021 Slabs in the greater Alpine area – interpretations based on teleseismic P-wave. The red circle at the lower edge of the map swathe marks the location of the city of Rijeka.

Looking at that section, the story seems quite a simple one, at least as far as the Marotta earthquake is concerned. Thrusting is shown in the very shallow section involving the Apennines, and at greater depth there is a detached ‘Adriatic’ slab sinking into the asthenosphere. The fact that it has detached can be taken as evidence for it being oceanic lithosphere, in which case the western continent-ocean boundary of the Adriatic Plate must be close to the present Adriatic shoreline of Italy. Shortening in this area is taking place within the Apennines as they pile up against the non-subductible Adria continental block, and the Marotta earthquake must be very close to that front, if not actually at it. The front itself would surely have moved east, by a few centimetres at least.

But what about the eastern side of Adria? Here things become more complicated. At very shallow levels the situation is almost an image of that in the west, with the Dinarides thrusting over Adria, but at depth things are very different. There is a detached slab, but it is much deeper than its counterpart in the west and it is labelled as a ‘detached European slab’. It is here that the orientation of the cross-section plays us false. That slab is interpreted as part of the European plate that was overthrust by Adria. Further south, we are told, there is no high-velocity material that might be assigned to oceanic lithosphere on the eastern part of the Adriatic Plate, but only hot mantle associated with Pannonian extension. However, most reconstructions assume that the eastern Adriatic Plate would have been oceanic. There are many mysteries still to be solved in this area.