When I first began working in the eastern part of Papua New Guinea, I was struck by the quite aggressively English names of the major features of its geography. I had no idea who Moresby, Owen Stanley, Lamington and Suckling might have been, but they seemed very much out of place where they were, and there was no doubt at all about the origins of the names of the twinned volcanic peaks, Mts. Victory and Trafalgar, that loomed over the airstrip at Wanigela.

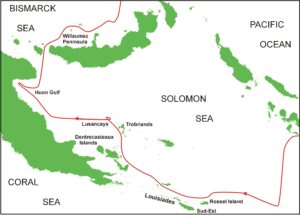

The Solomon Sea, showing the route taken by d’Entrecasteaux and the islands that he named.

But then, as our project moved offshore, a French influence began to appear. The largest of the chain of islands beyond the tip of the peninsula was not called South-East Island but, equally unimaginatively, Sud-Est (it has now largely reverted to its local name of Tagula, and a good thing too). Its neighbour is Rossel, and between them they dominate the islands of the Louisiades chain. Going north rather than east from the tip of the peninsula, we were confronted by the massive peaks of the D’Entrecasteaux Islands, and beyond them lay the coral flats of the Trobriands. West of the Trobriands lay a scatter of small islands and reefs known as the Lusancays, and if we had cared to cross the Solomon Sea, leaving the Huon Gulf on our left, and continued as far as the north coast of New Britain, we might have found ourselves on the spectacularly volcanic Willaumez Peninsula.

Who were these people?

The story of the names could be said to have begun on March 10,1788, when the two ships of the LaPérouse expedition, the Astrolabe and the Boussole, having already explored the Pacific coasts of the Americas from Chile to Alaska and visited China, Korea, Japan and the Philippines, left their anchorage in Adventure Bay, on the east coast of Tasmania and set sail for Melanesia. They were never seen again. Three years later, the frigates Espérance and Recherche left France under the overall command of Bruni d’Entrecasteaux to go and look for them. Like LaPérouse, d’Entrecasteaux never saw France again and nor did his second-in-command and captain of the Espérance, Jean-Michel Huon de Kermadec. Among the officers who went with them, all of whom did come back, were Lieutenants Rossel and Willaumez on the Recherche, and Lieutenants Trobriand and Luzancay on the Espérance.

The d’Entrecasteaux expedition may well have been the brainchild of Louis XVI himself, since he is said to have asked if there was any news of LaPérouse when he was on his way to the guillotine on January 21, 1793, but by the time the ships left France, on September 28, 1791 Louis was no more than a constitutional monarch-in-name-only whose power had passed to the Constituent Assembly. The political turmoil had spread to the navy and the men who manned the Espérance and the Recherche, and also the scientists, were mainly ardent revolutionaries while their officers were, by and large, royalists. By the time that d’Entrecasteaux left Tasmania, for a second time, on February 28, 1793, to carry the search to the Melanesian islands the divisions were becoming serious, even though no-one yet knew that the king was dead.

The Recherche and the Espérance. Painting by François Joseph Frédéric Roux.

We now know that LaPérouse’s two ships were wrecked in a single incident as they were leaving the Santa Cruz archipelago, half-way between the northern end of the Vanuatu chain and the southern end of the Solomons. It is a supreme irony that, having already sailed once completely around Australia and New Guinea, and having then searched New Caledonia and Tonga for signs of the missing expedition, d’Entrecasteaux actually came within sight of the island he was looking for, and even named it after his own vessel, but did not stop. A few months later the British captain Edward Edwards, returning after a successful search for the Bounty mutineers, sighted the same island from the Pandora and named it Pitt Island, giving Dumont d’Urville, who did eventually find traces of LaPérouse, a choice of names. He ignored them both and chose instead the one used by the inhabitants of Tikopia, which was Vanikoro (with a variety of spellings). Joseph-Paul Gaimard, who was on the corvette Astrolabe, named in memory of LaPerouse’s missing ship, reprising the role of surgeon/naturalist that he had first filled on the Uranie, wrote in a letter to his former commandant, Louis de Freycinet, that:

The island we landed on, which is surrounded by reefs that extend far offshore, was the one that was named Pitt Island by Captain Edwards, and is also the Recherche of d’Entrecasteaux. The two peoples who inhabit it belong to the Negro race. Far from being communicative as are the Polynesians, they are on the contrary very mistrustful and do not come out to any ships that they see: it was therefore necessary for us to go ashore in our own boats. It was in this way that we learned from the villagers that the place we had just reached was where Captain Dillon had anchored and that this ‘Ile de la Recherche’ was the island of the shipwreck.

Had d’Entrecasteaux not passed the island by, it is just possible that he might have rescued some of the crew, because although many were lost when the ships sank and others were killed by the islanders, there were enough of them left to build a boat and attempt to sail it to the Dutch settlements in the Moluccas. They never made it, but Gaimard believed that the boat had been too small to take everybody, and some would have been left behind. If so, then by 1828, when the Astrolabe arrived, they had been long gone.

But d’Entrecasteaux did pass by, heading north-west through the Solomons, and thence to the Papuan islands. The first large island he saw he named after Lieutenant Rossel, newly-appointed as his flag-captain, and showed where his political sympathies lay by naming the smaller islands beyond as the Louisiades. He then continued on to the d’Entrecasteaux Islands, turned north to the Trobriands and then west past the Lusancays to the Huon Gulf, which he named in honour of Kermadec, who had died in New Caledonia. He then entered the Bismarck Sea, passing within sight of the Willaumez Peninsula. This was the last place that he was able to name, because he died of scurvy at sea off the Hermit Islands, 200 kilometres ENE of Manus. Rossel continued to captain the Recherche, and Alexandre d’Auribeau, who had replaced Kermadec on the Espérance, took on the overall command of the expedition, by this time intent only on getting home.

Once within the Indonesian archipelago, the two ships made a number of stops. They stayed for a time at Kayeli, on Buru, and then at Buton, south-east of Sulawesi, where they were well received by the sultan after having assured him that they, like him, were allies of the Dutch. They reached Surabaya, on Java, on October 23, 1793, and it was then that the troubles in far off Europe intervened. One of the problems that faced explorers of distant seas in the late Eighteenth and early Nineteenth centuries was that when they visited the possessions of one of the other European powers, they could never be sure whether they were at war or not, and in Surabaya they learned that the Dutch, who were firmly in control of the city, were at war with France.

Rossel, who described the expedition in ‘Voyage de Dentrecasteaux’, ended his account at this point, and for what happened next one has to turn to the ‘Account of a Voyage in Search of LaPérouse’ written by the biologist, Jacques-Julien de Labillardière. An English translation was published in 1800. It is a complicated story, but the consequence for Rossel was that when he was at last able to leave Java it was on a Dutch vessel, the Hougly, that was flying the flag of the Batavian Republic that had become an ally of France. From Cape Town, then still also Dutch, the Hougly sailed away with all his charts and papers, but without him, and he took passage on a Dutch brig-of-war that was captured near the Shetlands. The Hougly was also captured, near St Helena, and Rossel was not reunited with his papers and able to begin writing his report until 1802, during the Peace of Amiens. They were returned to France at the urging of Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society.

Eighteen years later, Rossel was the only naval man on the committee of the Académie des Sciences which endorsed so enthusiastically the scientific work done during the voyage of the Uranie, and so the only one who really understood what Louis de Freycinet had been up against.