After the deaths of the two eldest de Freycinet brothers, Henri on 21 March 1840 and Louis on 18 August 1841, Alexandre Dezos de La Roquette wrote a joint obituary and summary of their lives for the Bulletin de la Société de Géographie (20, 2, 1843, pp. 501—539). He included in it, in a long footnote that extended over parts of four pages, a summary of the life of Rose de Freycinet. In translation, the footnote reads:

Rose Marie Pinon, born in Saint-Julien-de-Sault, department of the Yonne, on September 29, 1794, was raised in Paris and received an extremely thorough education., On June 6, 1814 she married Louis de Freycinet, at that time a capitaine de frégate. Barely three years had passed since their marriage when Freycinet obtained command of the Uranie expedition. Although of a gentle, reserved and even slightly shy character, Madame de Freycinet, always ready to devote herself to those she loved, first thought of following her husband on the long journey he was about to undertake. At first he rejected the proposal she made to him, but then the strong attachment he had for her decided him to give in to her pressing entreaties. Not at all frightened by the dangers she might run, she calmly made her preparations for departure. As soon as her effects were on the vessel, she went on board in the evening, dressed as a man, to deceive the eyes of those who composed the crew of the Uranie, and it was only after the stopover that was made at Sainte-Croix de Ténériffe (October 27, 1817) that she resumed, never to leave them again, the clothes of her sex. Her health was perfect during the whole trip, and she did not experience a single moment of seasickness.

In moments of danger she showed the greatest firmness, and, in the somewhat difficult position she had created for herself, she knew by her reserve, by her modesty and by her excellent mind, how to attract the respect of the officers on board, but also of all the foreigners she met during this long voyage. Each time the corvette touched a port and it was learned that the captain’s wife was on board, the English, Spanish, Portuguese and Dutch governors or captains hastened to welcome her with the greatest distinction. All of them organized parties in her honour; all would have liked to retain for as long as possible this amiable Frenchwoman who had not been afraid to venture on the ocean to come and visit them; and several, among whom we will cite M. Mailac, from the Ile d France, composed pieces of verse in her honour.

“Our crossing from Sydney to Cape Horn,” she said in a letter she wrote to her sister from Montevideo, dated 14 May 1820, “had been superb, and we had already reached the anchorage in Cook’s Bay of Good-Success, which is not very far from it and where Louis was to make some observations. But no sooner were we anchored than a terrible gust of wind broke out and drove us towards the rocks that line the shore; we would certainly have perished there if Louis had not had the presence of mind to cut the cables and set sail. We were happy to escape, to three days of bad weather”

At the moment when the Uranie was fleeing this danger and passing a short distance from the reefs on which she might have been destroyed, Madame de Freycinet has often related that, knowing the full extent of the danger, she nevertheless conceived a strong desire to watch whatever happened. Her head on her hand, barely breathing, she followed everything that was happening with a worried and eager attention; but in order to prevent any cry from betraying her fear, she had placed her finger to her mouth. In her preoccupation, this finger crept imperceptibly between her teeth, which penetrated it so deeply that the blood soon streamed down the arm; it was only then that she realized the state she had got herself into.

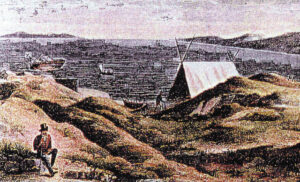

When the corvette was shipwrecked in the Falkland Islands, Madame de Freycinet, despite her husband’s entreaties, did not want to part with him for a moment, and as he was the last to leave the ship, as his duty obliged him to be, she, too, disembarked only after the whole crew was safely ashore. All, seeing her, at the most terrible moment of the shipwreck, were struck by her resignation and by that admirable courage which women so often show in great circumstances. Overwhelmed with anxiety and fatigue, and lying in a tent where the rain was penetrating, Freycinet, whose health was already impaired, fell dangerously ill, and for eight days people feared for his life. Madame de Freycinet’s position was dreadful, for to the fear of losing the man for whom she had, so to speak, sacrificed herself, was added that of being, aged twenty-six, the only woman among one hundred and twenty-five men, unprotected and ignorant of whether she would ever be able leave that unhappy place. The moments of anguish she then experienced were dreadful; her absolute confidence in Providence alone could sustain her courage.

A portion of Alphonse Pellion’s view of the Uranie camp showing the wreck offshore. (Figure 7 in McCarthy, M. 2005, Rose de Freycinet and the French Exploration Corvette L’Uranie (1820): a Highlight of the ‘French Connection’ with the ‘Great Southland’ International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 34(1):62 – 78. Original in the WA Maritime Museum.

M. Freycinet recovered, and it was not long before they returned to France. The author of this article, a friend of the commander of the Uranie, often saw Madame de Freycinet and was able to appreciate her excellent qualities, her lively and piquant spirit; he regrets not having taken note of the curious details which she gave with as much simplicity as modesty on what had struck her during this long journey, on her meetings with the savages of the islands which the expedition visited, etc. etc. She described the sensations that so many new objects had made on her, in letters written to her family, which her husband had, it is said, collected to perhaps publish one day, and which we were unable to obtain; we only know that she rendered her impressions there in the most piquant fashion. Cholera having broken out in Paris, Madame de Freycinet, who had already been ill for ten months with a gastric attack, wanted to treat her husband, who had been stricken by the terrible scourge. She soon fell victim to it, and on 7 May 1832, she died, congratulating herself on having saved the man whose existence seemed to her much more precious than her own. We have seen that an islet discovered during the voyage received the name of Rose Island; a very beautiful dove was also called Pinon in honour of the wife of the commander of the Uranie.

Although Roquette described himself as ‘a friend of the commander of the Uranie’, i.e. of Louis, it is not clear how close this friendship might have been. He was five years younger than Louis, and not a nautical man, and he would have been away from Paris for much of the period 1831 to 1839, when he was the French ambassador, first to Denmark and then to Norway. Their relationship presumably arose from their shared membership of the Société de Géographie,. Roquette was its secretary in 1829, and after he returned from his ambassadorial posts he seems to have taken an increasingly active role.He ultimately became its Honorary President, but his contributions to have been as an editor, a translator and a biographer; there is no indication that he ever did serious geographical work himself. While there is no reason to doubt that he was well acquainted with Louis, and therefore with Rose, he got some of the details wrong. He would not have had access to her ‘Journal for Caroline’ and, as he tells us himself, he never saw her letters to her mother. According to Rose, in both her diary and her letters to her mother, it was actually after her first visit ashore, which took place in Gibraltar, that she abandoned the clothes of the teenage boy in which she had boarded the Uranie, and she never wore them again except as a convenience in the very difficult landings at the quarantine station on Tenerife. Roquette’s description of the arrival in the Falklands was also different. According to Rose, and there is no reason to disbelieve her, she remained on board the Uranie for several days whilst the camp was being established ashore, uncomfortably, certainly, because the vessel, which had been run aground and was tilting at an increasingly alarming angle, but less uncomfortably than she would have been in a hastily erected tent.

One of the most interesting points in this brief account is in the last paragraph, where Roquette mentions Louis assembling letters written by Rose to ‘her family’ for possible publication. These, presumably, were the letters that Rose wrote to her mother, copies of which are now preserved in the Mitchell Library in Sydney, and what he had to say about them confirms the supposition that they were copied under Louis’ instruction and possibly by Louis himself. It is, however, remarkable that after Louis died Roquette was able to find neither the originals nor the copies. The copies were, after all, preserved, presumably at Freycinet in the Drôme, and it therefore seems the Roquette was not a close enough friend of the family to have access to them.

This makes it all the more interesting that Roquette was able to quote from a letter written by Rose to her sister Stéphanie after the rescue. It was sent from Montevideo, and we know that there were ships going from there to the Mascarenes, because some of the crew who had joined the Uranie on Réunion and had left the Falklands in the Physicienne took the opportunity presented by Louis’ need to pay off some of the crew in order to reduce overcrowding and went home directly. According to Arago (Promenade Vol. 1, p.xxviii), there were four of these men in the ‘premier comp. des ouvriers detaches á l’Ile Bourbon’, three of whom were blacksmiths and one a carpenter, indicating that it was not merely stores that the Uranie took on board on that island. They travelled aboard a Bordeaux-based vessel called the Espérance and the letter probably went with them. From Réunion the letter would have been forwarded to Stéphanie on Mauritius, where she was living at the time and must have been brought back by her when she returned to France in 1824. It may be that after after Louis died Roquette had better access to Stéphanie in Paris than to the de Freycinet family in the Midi.

The survival of this letter raises yet again the question of why the letters Rose wrote to her mother after the shipwreck have not survived, even as copies. If the letter to Stéphanie could survive the complicated journey to Mauritius and then to France, why did not the letters that were sent more directly to her mother? One possibility, of course, is that they did, but that whilst Louis was happy to assemble the letters describing the successful voyage of the Uranie as far as Sydney, the letters describing the shipwreck and its aftermath were all too painful for him to wish to preserve .