Was Rose de Freycinet an artist? Certainly not, if she can be judged by the only drawing that may possibly be by her that is readily accessible. More of that later.

She did, of course, have many other talents and abilities, as revealed in her letters to her mother. These have survived only as hand-written copies, now held by the State Library of New South Wales, some and perhaps all of which were written in her husband’s hand and were presumably copied by him from the originals.

He may have censored parts of what his wife wrote. He certainly crossed out and re-wrote some short sections, because those amendments can be seen in the copies, and there is also the circumstantial evidence provided by the much lighter editing applied by Charles Duplomb and the fourth Baron de Freycinet to the section of their published version of her journal where the letters were used to fill a major gap left by a missing notebook. There is a very marked contrast with their unrelenting attack on the journal written in Rose’s own hand. Were they were less inclined to edit the letters because they thought that they had already been edited by Louis? Or was it simply that they found less in the letters that they regarded as controversial? It is instructive to look at what they did omit from the letters they used.

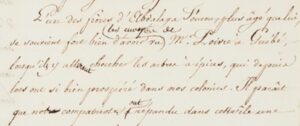

A part of one of Louis de Freycinet’s transcripts of his wife’s letters, placed on-line by the State Library of New South Wales, with each image identified by six-digit number preceded by the letters FL

In this first review on this blog of the omissions, only Letter 12, written during the long transit from Rawak to Guam, is considered. Rose wrote (and the Baron and Duplomb decided to ignore) that:

We have been sailing for so long in the tropics that the frequency of thunderstorms has made me brave by familiarity, but recently there was one that frightened me more than any of the others. It seemed to me, in my little wisdom, that we skirted too close to an island that was, in my opinion, very threatening, but when I made this very relevant observation I was told that there was no danger, because the wind, whose violence I dreaded, was for us a powerful friend, blowing from the land and consequently taking us away from the headlands that seemed so dangerous to me. From which you will not fail to conclude that your daughter is not yet very skilled in navigation. I am happy to admit it. [FL678856 – FL678858]

Why should this have been left out? It is no great fault in Rose that she should have had such thoughts. Why should she have been aware of this particular aspect of navigation under sail? True, she had been on board for more than a year, but seldom in a situation where there was any great risk of being swept on to rocks. Nor is the passage without interest, because it gives us a very direct insight into her feelings at this stage in the voyage, when the Uranie was threading its way through the reefs and shoals of the Moluccas. Its omission is simply a mystery.

The reasons why the next omission might have been made are more obvious and, as with so many of the sections treated in this way, what was left out is full of interest and incident.

Something just happened, the unfortunate consequences of which we will suffer throughout the rest of the voyage. Having had a fairly considerable amount of laundry on board, and having on Rawak only a single pool, in which the laundry would have been badly rinsed, I was obliged to send it to be washed at the watering place we use on Waigiou Island. Four days ago a canoe that was carrying a large part of it was caught by bad weather, wrecked and cast up on the beach: the men in it all got ashore, where they were rescued by villagers who were living nearby, but the laundry had all vanished completely and has been [FL676878] lost. Two of the villagers brought two of our men back on board the same day in one of their canoes, and they told us about the accident. As the bad weather continued, it was only today that we were able to bring back the wreckage of the canoe and the rest of the men, to whom we had sent food.

As our dinner guest Moro was leaving us the day before yesterday, he expressed in a manner as comical as it was naïve, his regret at leaving our good cooking behind, and deplored the fate that will consign his palate to the insipidity of sago: this pith of a species of palm is the staple diet of the people of all these islands. [FL678876 – FL678878]

The loss of the laundry is an episode that Louis de Freycinet also recorded, as did Joseph Gaimard (but not Jacques Arago), so there was no great secret about it, but Rose gives us some information that nobody else did. Perhaps it was the suggestion that it was she herself who took the decision to send the laundry across the narrow strait to Waigeo that her editors thought should be suppressed. It can hardly have been the fact, oddly juxtaposed to the loss of the laundry, that it a man from the Ayu islands took only a few days to become addicted to French cooking, an episode that could be considered pure comedy. There might, however, have been more written by Rose about this than Louis chose to copy, because the reason that Moro left was because the Kimalaha of Gebe had arrived.

Much of what Rose, and Louis, recorded concerning the voyage from Dili to Guam via Rawak was concerned with the sicknesses (malaria and dysentery) rampant among the crew and the état-major. Neither of them suffered in this way, largely because they had drunk only distilled water while in Coupang and had eaten from only a very limited range of fruit, but caution was discarded when they reached Rawak, and Rose suffered accordingly. The next omission comes at the end of period after an excursion by some of the état-major to Manouran when she thought, with how much justification is hard to tell, that she might have died. Just three sentences were left out, and they seem to have little in common.

Do not scold me for having eaten an unknown fruit, but rather praise the honesty with which I tell you everything, and conclude that you can rest assured when I write to you that we are doing very well.

I owe this much to the Gebeans, to say that they behaved very well with regard to the effects which were still ashore, and on account of which their temporary proximity was feared.

We are just now sailing from here, God knows where I will complete this letter….! [FL676885]

It is after the departure from Rawak that we come to the point where we can imagine Rose as an artist. It is associated with a section that the editors retained but rendered frustratingly opaque by not including the drawing mentioned in it. It was Gaimard who preserved it for us although, presumably in deference to Rose’s highly irregular presence on board, he attributed it to Louis, writing that “On the 23rd (of February, 1819), the Commandant saw a huge flatfish, at least 8 feet long, with a fin on its back: it appears to be a new ray”, and added that a sketch in the margin on the following page was based on a drawing by “M. D Freycinet” (Gaimard’s Diary, p.380).

Left: Marginal drawing on p. 381 of Gaimard’s diary, attributed to Louis de Freycinet but probably by Rose de Freycinet, of a ‘fish of enormous size’ encountered north of New Guinea while the Uranie was en route from Rawak to Guam. Right: The giant manta ray, the unwitting victim of this artistic effort (Image, Oceana website)

Gaimard was the only diarist, apart from Rose herself, to record her presence on board the Uranie, but he never made much of it and may have decided to be reticent on this occasion. Her husband, the supposed author of the sketch, did not even bother to mention the encounter with the giant fish; the relevant section of Volume 2, Part 1 of the Historique is largely devoted to the prevalence of malaria and dysentery amongst the crew and the état-major. What Rose herself wrote points much more directly to her as the originator of the sketch. She was bored by the long transit but ……

After having seen, but only from a distance, the small Anchorite and Admiralty Islands, and being always poised between calms and thunderstorms, the only event that could have interested me for a few moments was the encounter we had a few days ago with a shoal of large fish, the shape of rays but of an enormous size, with long horns on their heads: as chance would have it, it was I who saw them well enough to make a sketch, which I did, because it seems that this species of fish is not known. [FL676890]

This clearly implies that she was the only person who say the fish clearly, and therefore the only person in a position to make a sketch of them.

The last omission made by the editors from Letter 12 was also the letter’s finale. It was written from Umatac, on the southern west coast of Guam.

I hasten to add what I can to my letter, already so long, because when we arrived in this bay we found here a Spanish vessel coming from Manila and which, being due to leave within two days for Acapulco, will take care of our dispatches. Imagine how happy I am to have been conscientiously setting down the details of our journey from Diély while we were en route, and also to be able to add to them that, according to the testimony of Louis, that the hardest and the most dangerous part has been completed. [FL676897]

Sadly, this was one prediction by Louis that was to prove very, very, wrong.