When the Uranie was approaching Rio de Janeiro, it had on board a very unhappy Rose de Freycinet. The journey thus far had been enough to show her what long voyages under sail in rather small ships were really like, and the most recent contact with land, on Tenerife, had been pure misery. The French consul there had been almost useless, and the trips ashore, which could take her only as far as the primitive lazaret, had been hazardous enough to force her to again wear men’s cloths, which she hated. The previous stay, in Gibraltar, had been better, but it was frighteningly close to France, with the ever present possibility that the French government might persuade the British to send her home. And – she had learned that their unscheduled visit to Brazil, coupled with the delays in trying to leave the Mediterranean against adverse winds and currents in the Straits of Gibraltar, would add eight months to the planned two years of the voyage.

All that changed soon after they had landed, because in Rio she found two new friends, both older women and French aristocrats, who took her under their wings. One of these was the Natalie Sumter, wife of the US Ambassador, the other Madame la Contesse de Roquefeuil, canoness of Remiremont, a French émigrée who, after the revolution in France, had sought refuge first in Portugal and then in Brazil. Of them Rose wrote:

When one is in a foreign country one of the things that delights one enormously is to meet with one’s compatriots. Mme. de Roquefeuille is a person who has often found herself in that position; she therefore hastened to introduce us to the American ambassador, whose wife is French; the very day that Louis met her for the first time, M. Gestas, her nephew, took my husband to meet this amiable Frenchwoman.

I will not be able to prevent myself from talking to you at great length about this family and that of Mme.de Roquefeuille, because with them, I have experienced the first pleasant sensations since my departure. One of them has treated me like a daughter, and the other became an almost intimate friend within days. [State Library of New South Wales FL686989]

The ‘intimate friend’ had had a very different upbringing from Rose, who had lived in the school her mother had started after her husband had died. Born Marie Louise Stephanie Beatrix Nathalie de Lage de Volude at Versailles in 1782, the girl who was to become Natalie Sumter was a god-daughter of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. When revolution broke out in France she was spirited away to New York and was raised in the household of Aaron Burr, who treated her almost as his own daughter. There she remained until Napoleon’s policy of reconciliation with the old aristocracy made it safe for her to return to France, in 1801, the year Burr became vice-president of the United States, and three years before he killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel. The journey was a turning point in her life, because while at sea she met Thomas Sumter, a planter’s son from South Carolina fourteen years her senior, who was on his way to a position in the American legation in Paris. In 1802 they were married.

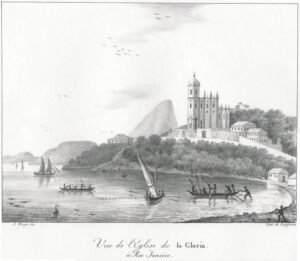

Gloria Cove, where the de Freycinets stayed while in Rio, in a house found for them by the Comte de Gestas

But what of the Abbey of Remiremont and the Contesse de Roquefeuille ? And what, indeed of M. Gestas, her nephew, who played something of the same role to Louis de Freycinet as his aunt did to Rose? Aymar de Gestas was no ordinary ‘Monsieur’, he was a count. His story goes back to 1781, when Marie-Josèphe-Catherine de Roquefeuil, maid of honour, to the Duchess of Bourbon, the sister of the Contesse/Canoness, married Sébastien-Charles-Hubert de Gestas, marquis de Lespéroux, then aged 29. It was noted at the time that although the dowry was insignificant, the alliance was illustrious; the king himself signed the marriage contract.

The couple had two sons, the eldest, Louis; the youngest, Jacques-Marie-Aymar. The latter, who was to become the Comte de Gestas whom Rose knew in Rio, was born in Paris on June 24, 1786, in the parish of Saint-Roch. When France turned revolutionary, Sébastien de Gestas remained in the army but also remained a monarchist, involved in secret intrigues. These, almost inevitably, took him to the guillotine in December 1793. His wife had previously made her escape to Germany but died there, and the two children went to her sister the Contesse, who had fled from France to Portugal after the community of the Abbey of Remiremont was dissolved. Dissolution was inevitable, because the community had been very far from being revolutionary. According to Wikipedia, it had been established early in the 7th Century, but ….

“gradually, the women of Remiremont stopped following the Benedictine rule and became secular canonesses, who did not take perpetual vows, and were free to resign their prebendaries and marry. Remiremont was very exclusive. Canonesses were admitted only from those who could give proof of 200 years of noble descent. Enriched by the Dukes of Lorraine, the kings of France and the Holy Roman Emperors, the ladies of Remiremont attained great power. They lived independently within the abbey with their own circle of friends and servants. As prebends, they each received a share of the abbey’s considerable income to dispose of as they wished, and could leave to visit family, sometimes for months at a time.

In the 17th century the ladies of Remiremont fell away so much from the original monastic style of life as to take the title of countesses. In church they wore long white mantles trimmed with ermine. They were obliged to live at the abbey three months in the year in secular houses built in a large enclosure around the church. Many kept carriages and gave balls, concerts, and other entertainments.”

For a stranger in a strange land, such a canoness, or countess, sounds a good friend to have.

By the time the countess had left Portugal for Brazil with the royal family, the boys were back in France. Amnestied after the terror, they became Bonapartists, the elder brother with such enthusiasm that he enlisted in the Grande Armée while still not officially old enough to do so, and died of wounds after the battle of Friedland in 1807. His brother, now the count, took a more pacific route through life, but with such success that Napoleon appointed him as his diplomatic representative to the Portuguese government, despite the fact that John VI had just been driven from his kingdom by the French invasion.

When the king left Portugal for Brazil on September 29, 1807 it was not only his court. but many of the French emigré community who went with him. Among their number were the canoness and her brother, the Vicomte de Roquefeuil. This was a time when even nations that were at war with each other maintained diplomatic missions in each other’s countries, and as an accredited diplomat Aymar eventually joined them. The family bought the Tijuca property, a few kilometers from the centre of the capital, a mountainous, shaded and watered region that has been preserved to this day as an urban national park. The vicomte did not long survive the move, but Aymar and the countess were still living in Tijuca when the Uranie arrived.

Strangely enough, the people of the Uranie were meet another de Roquefeui during their voyage. This was the brother of Camille de Roquefeuil, a member of the Cahuzac branch of the Roquefeuil-Blanquefort family, and therefore a distant relative of the Mme de Roquefeuil of Tijuca. In 1815 Camillewas selected by the Duke of Richelieu to take command of the Bordelais and open up new avenues for French trade, in a circumnavigation that lasted thirty-six months. When the Uranie was anchored off Mauritius, the Bordelais was tracking along the north-west coast of America, having entered the Pacific via Cape Horn.