The 12 May 2025 Royal Institution lecture by the Earth Science historian Naomi Oreskes on ‘Rethinking the origins of plate tectonics’ has led to an increased interest in those origins. Much of the discussion has been concentrated on identifying the people who made the really crucial advances, but it is also interesting to think about the degree to which they were essential to those advances. If one of them had not existed, would the acceptance of plate tectonics have been significantly delayed, or was the time so ripe for that particular advance that someone else would have made it only a short time later?

What were the crucial advances? We might identify the defining of the dipping seismic zones associated with island arcs, the palaeomagnetic evidence for the relative movement of continents, the discovery of the rift on the crest of the mid-Atlantic ridge, the formulation of the concept of sea-floor spreading and the discovery of linear magnetic anomalies in the oceans.

The first of these is, of course, inextricably linked to the name of Hugo Benioff, to which the name of Kiyoo Wadati has been belatedly added, but it also illustrates the difference between those who were pioneers and those who pushed things along. Wadati published his paper with a contour map of the depths of earthquake foci associated with Japan subduction in 1935, but it attracted little attention. Had he suggested that his map showed a fault down which a whole ocean was plunging into the mantle he would have been laughed to scorn, and what he did suggest was that that the inclined intermediate-deep earthquake zones were regions of weakness, and possibly traces of drift, of the Japanese islands. Had he not published at all the progress of plate tectonics would have been little different. Would it have been different without Hugo Benioff?

Benioff did not publish the results of his study of deep earthquakes until 1949, right at the start of the observations that led to mobilist ascendancy, in a paper with the title ‘Seismic evidence for the fault origin of oceanic deeps’, but his proposed mechanism for the formation of the faults was very far from subduction. Instead, it was, in his view, the differential stress due to the elevation difference along a continental margin (specifically the South American and Tonga-Kermadec margins) that led to the formation of a deep-penetrating fault. It was not until sea-floor spreading at constructive plate boundaries became respectable that people seized on the seismic data as providing the necessary destructive part of the story. Benioff. like Wadatim was a true pioneer, but it would hard to see him as a driving force in the development of plate tectonics.

Palaeomagnetism should have established the reality of continental drift by at least 1956, the year in which Keith Runcorn published his paper on Palaeomagnetic comparisons between Europe and North America’. In this he compared the ‘polar wander’ curves for the two continents and showed that they were compatible only if the two continents had been immediately adjacent to each other for a considerable part of geological time. The publication was all the more impressive because Runcorn was reversing his long-held belief that it was the magnetic poles that had moved and not the continents. However, the paper appeared on pages 77-85 of Volume 8 of the Proceedings of the Geological Association of Canada, a journal that no longer exists, and it caused barely a ripple. By the time Runcorn reprised the topic in a Royal Society symposium in 1965, plate tectonics was well on its way to becoming established. It was much more a case of plate tectonics forcing acceptance of palaeomagnetism as a valid means of tracking the movement of continents than of palaeomagnetism contributing to the development of plate tectonics, which would have been little different had he never published at all.

And so to bathymetry, and three names, Tharp, Hess and Dietz.

Perhaps the most important single contribution made by purely bathymetric studies was the identification by Marie Tharp of a rift running down the centre of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. She saw that in 1952, and it was an obvious feature of the map she drew in 1957. But, being a woman, she was widely ignored. Typically, when a paper mentioning the rift was finally published, in 1967, her colleague, the data-gatherer Bruce Heezen, was the sole author.

Sea-floor spreading? In November 1962, Harry Hess published his History of the Ocean Basins, which presented the concept, in a volume honouring the petrologist Arthur Buddington. It was not a high profile presentation, and he had already circulated the paper promoting idea in the previous few years, but there was little in either that was not also in Robert Dietz’s Nature paper Continent and Ocean Basin Evolution by Spreading of the Sea Floor. ‘Sea floor spreading’ was also a catchier title than anything Hess had produced and, enormous as his contributions would become, it is unlikely that acceptance of the underlying idea would have been much delayed had he not existed. If, on the other hand, Dietz had not existed, then Hess’s idea would probably have eventually won through, but probably much more slowly. It was not the idea itself, but its application as an explanation for the Mason-Raff (or Raff-Mason) magnetic anomalies that triggered the overthrow, in a remarkably short space of time, of fixist ideas of global geological evolution.

Was it then Ron Mason, or Arthur Raff, or both, whose absence from the scene would have significantly delayed the advent of plate tectonics? I would put Mason before Raff, because he was the man who suggested that it might be interesting to tow a magnetometer on an oceanographic cruise, but his mere existence was not enough. He was not a man to strongly assert his ideas.

Who, then?

There is another way of looking at this particular history, which is to identify people without whose intervention plate tectonics might have been delayed by years, and if this is done a name emerges that is now almost forgotten. What was needed was someone who, when Mason casually suggested that it might be interesting to tow a magnetometer behind an oceanographic survey ship, immediately set about ensuring that Mason, the magnetometer and the ship would be brought together. And who, when the possibility emerged, a few years later, of having a magnetometer towed behind the ship that was to carry out a systematic bathymetric survey of the ocean off the west coast of the United States, and no no institution was prepared to fund it, used his own limited research funds to make sure that it happened.

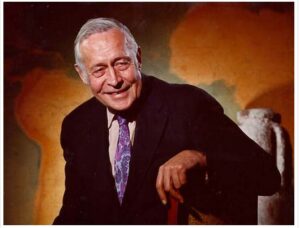

Step forward Roger Revelle, father of plate tectonics.

Roger Revelle, director of Scripps Institution of Oceanography, 1950 – 1964