On 12 May 2025 the Earth Science historian Naomi Oreskes delivered a Royal Institution lecture to a live and online audience with the title ‘Rethinking the origins of plate tectonics’. In the advance publicity, the theme of the talk was summarised as follows:

Many historians have thought that U.S. Navy funding of oceanography paved the way for plate tectonic theory. By funding extensive investigations of the deep ocean, Navy support enabled scientists to discover and understand sea-floor magnetic stripes, the association of the deep trenches with deep-focus earthquakes, and other key features. Historian of science and geologist Naomi Oreskes presents a different view: the major pieces of plate tectonic theory were in place in the 1930s, and military secrecy in fact prevented the coalescence of plate tectonics, delaying it for three decades.

It would, in fact, be surprising if any serious historians associated the US Navy with the link between the trenches and deep earthquakes, which was demonstrated by Kiyoo Wadati before the Second World War and Hugo Benioff after it. The assumption of naval funding for the surveys that first defined sea-floor magnetic stripes is more common, but in fact they were programmed as purely bathymetric studies by the US Coast and Geodetic Survey, and the magnetometry was added only reluctantly and was funded entirely from the discretionary budget of Roger Revelle, head of Scripps Institution of Oceanography (H. W. Menard, The Ocean of Truth, pp. 72-73).

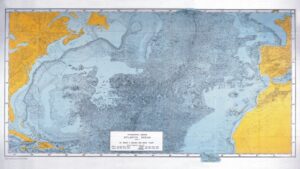

Figure 1. The Tharp–Heezen 1957 map of part of the Atlantic Ocean. An example of the sort of maps that could be constructed from US Navy echo-sounding data available at that time. Although the mid-Atlantic rift is well-defined, the pattern of fracture zones is not, and although the westward bulge of Africa would appear to fit snugly against the continental slope of eastern North America, sceptics would surely have been quick to point out the lack of any space for the Iberian Peninsula.

Those suppositions may be incorrect; that does not necessarily validate Oreskes alternative history, but to suggest that the US Navy was in possession of bathymetric data of sufficiently wide distribution and sufficiently good quality in the mid-1930s to lead to the development and acceptance of plate tectonics is pure fantasy.

To me at least, her talk seemed to completely miss the point. Revisiting the theories, suggestions and observations that were around in the thirties may ask the question of why it was not until the late 1960s that ‘continental drift’ in its plate tectonic form gained general acceptance, but it also answers it. The key data were missing. The more interesting question, given the data that Oreskes presented as having been published, is why was it that continental drift, in any form, remained anathema to so much of the geological establishment (at least in the northern hemisphere, attitudes in the south were very different) well into the 1960s. Why was the alternative world of tectogenes and geosynclines so resistant to change? The claim made by in the advance publicity, of it being all due to military secrecy preventing the release of US Navy oceanographic data is totally inadequate as an explanation.

One obvious problem of Oreskes as a commentator on this era is that she was not around when it happened. By the time she was born, in late November 1958, the first results of systematic magnetic surveys of the ocean crust off the west coast of the US had already been published, and by the time she graduated, in mining geology from Imperial College’s Royal School of Mines in 1981, plate tectonics was very generally accepted as the dominant geological paradigm. She has none of the ‘feel’ for geological attitudes in the 1950’s and 1960’s that would have come from actually having been there, and she completely ignores the fact that marine geologists were a very rare breed in the immediate post-war period. The majority of geologists worked in continental geology, a far cry from the relative simplicities of the oceans, and what was known of oceanic geology did not suggest that it was very interesting. It is no accident that some of the fiercest opponents of plate tectonics were to be found in continent-spanning Russia, where Vladimir Beloussov ruled the roost, and tolerated no dissent.

Nor did Oreskes mention data quality in her talk. It is all very well to talk of data quantity, but when new ideas are being promoted, and resisted, quality is vitally important. Kiyoo Wadati may have interpreted the available seismograms correctly, but the inadequacies of the seismograph networks of the time made it all too easy for his conclusions to be questioned; his work had little impact. Benioff published his seminal work in 1949, but it was the establishment of the World-Wide Standardized Seismograph Network in the 1960s, largely out of a need to monitor nuclear weapon tests, that finally gave the scientific world confidence in the universality of his dipping seismic zones.

And, most notably, although Oreskes gave a nod to palaeomagnetic evidence, which was ambiguous and widely dismissed at the time, she barely mentioned the marine magnetic anomalies that were so important and which could not have been discovered prior to the Second World War. The necessary instrumentation simply did not exist.