Back in the 1950s, one rule about US oceanographic cruises was that there would be no women on board. Marie Tharp may have mapped the world’s oceans better than anyone before her, and drawn the most beautiful maps, but there was no question of her ever actually going to sea. Scripps Institution of Oceanography was a little bit more relaxed, and some women had gone on short cruises, but never on major expeditions. So, when Russell Raitt left San Diego as chief scientist on the R/v Baird, one of the two ships taking part in the months-long Capricorn Expedition, his wife was certainly not going to be allowed to accompany him.

Helen Raitt was not, however, a woman to sit quietly at home while her husband was doing exciting things in the Pacific. If she could not be on the Baird when it was at sea, at least she could be there when it was in port. The first place at which that was feasible was Suva, capital of the Fiji islands, and flying there in 1952 would have been an adventure in its own right. Helen did that, and while in Suva she found a way to get to the Baird’s next port of call, Nuku’alofa, capital of Tonga. That was not a trip that could be made by air, and with ships to and from the islands few and far between, and with very limited accommodation for passengers, Helen wisely booked her passage off the island as soon as she arrived on it, and then set about studying the language and customs of the islanders.

The Baird duly arrived, and Helen met her husband again, but during its stay a problem arose. One of the scientists needed to get back to the US urgently (or at least what passes for urgently in the South Pacific), and there were no berths vacant on the next ship to leave the island, and the one after it was a long time away. The only solution was to find a passenger who could be persuaded to give up their place on the ship that was almost ready to leave.

Step forward, Helen Raitt.

The scientific crew of the Baird, just about to dock in San Diego. Helen Raitt on far right, Ron Mason, far left.

She took over the empty berth on the Baird, made herself almost indispensable on board, and remained with the ship until it returned to San Diego. And when she got off the ship she wrote a book, ‘Exploring the Deep Pacific’, about the expedition and the people who took part in it. Amongst those, on his first ocean cruise, was an English geophysicist called Ron Mason, and during it he made what was really the first successful scientific use of a ship-towed magnetometer. The readings of magnetic field were recorded on paper charts 18 ft long, and to work on them Ron favoured the nighttime, when he spread them around the ship’s laboratory at a time when few of the other scientists on board wanted to use it. He was, as Helen described him, a ‘lone wolf’, although not so wolfish that he was not prepared to share with her the hard-boiled eggs he had in his pocket to sustain him through the long night watches. The technique he developed during those nights was to be vital when, a few years later, he was recording and analysing the records that were going to lead the discovery of oceanic magnetic anomalies, the famous Raff-Mason lineaments.

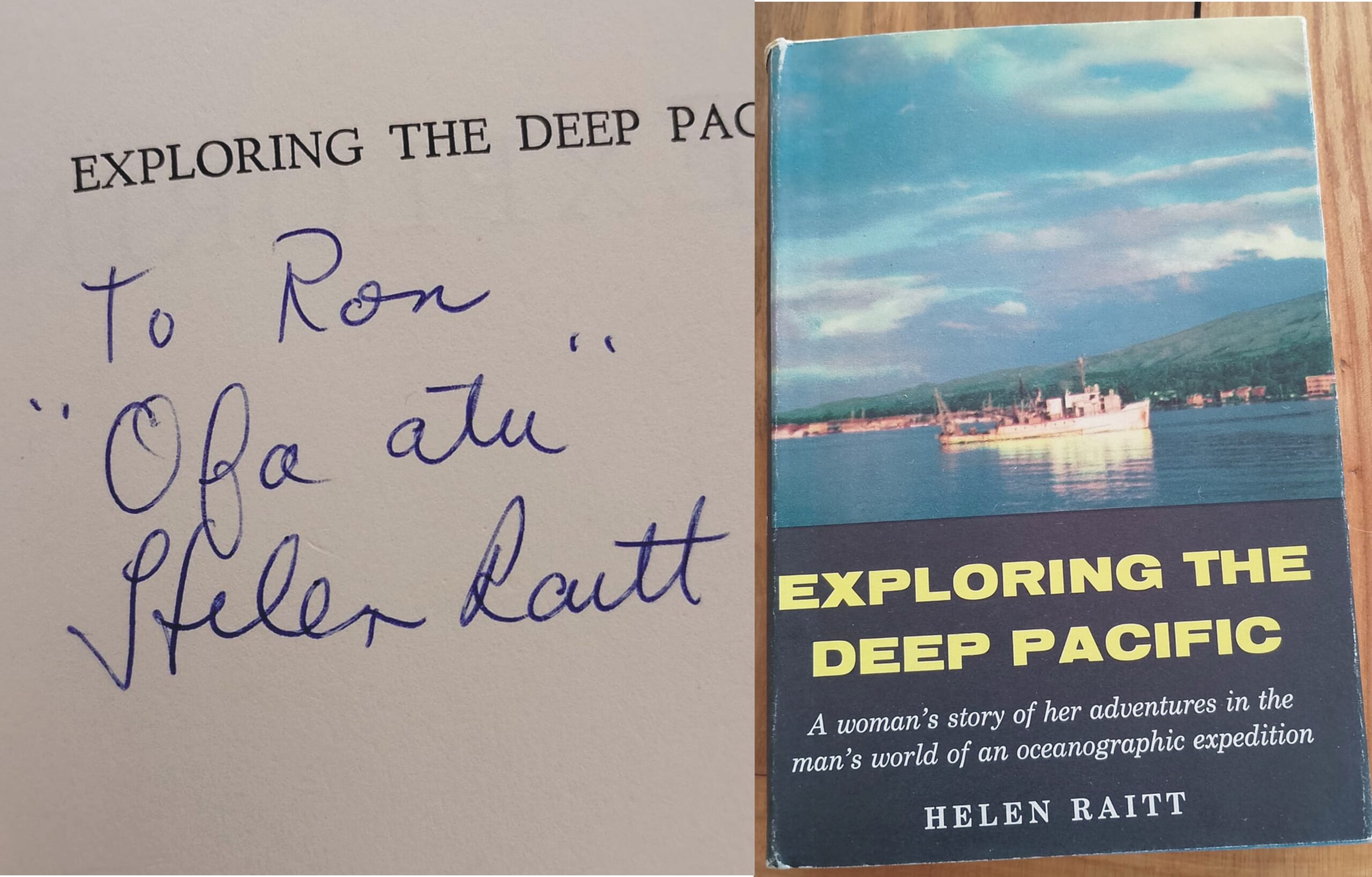

Seventy years later, I volunteered to give a talk about Ron, whom I had come to know well as my PhD supervisor, to the History of Geology Group affiliated to the Geological Society and, having delivered the talk, I was asked to write a short summary for their journal, Geohistories. That led me to look up Helen’s book to cite it as a reference (I had a copy, but was away from home), and there, on the website of World of Books, I found for sale, not just a copy, but the copy Helen sent to Ron, with her message to him.

‘Ofa atu’ is Tongan Polynesian for ‘with love’.

For what it was, the book was ridiculously cheap, but it is no longer for sale. I now have that bit of history in my own hands.

And it is quite a thought that, whenever I went into Ron’s office as a student or, later, as a staff member, that same book was probably in the bookshelves next to his desk.