Once again, one of my Bouguer blogs is being prompted by a post on LinkedIn, but this time the connection with geophysics is a bit tenuous. I might call it non-existent, were it not for the fact that this is clearly not the view taken by some academics.

When a book with the title ‘Geologic Life’, and the subtitle ‘Inhuman Intimacies and the Geophysics of Race’ appears, and it generates a considerable amount of comment, anyone who has spent an entire (and quite extended) working life in geophysics, as I have, is bound to be intrigued. And when the author, Kathryn Yusoff, is Professor of ‘Inhuman Geography’ at Queen Mary College, London University’s eastern outpost in the Mile End Road, where I once taught geophysics, a closer look seemed justified. Since geography, when I was at school, was divided into human (people, where they were, what they did), and physical (land-forms, in the broadest sense, and therefore closely akin to Quaternary geology), I hoped, at the very least, to discover what inhuman geography was.

That quest did not go well, even though the word ‘inhuman’ appears in the first paragraph of the Introduction chapter in Yusoff’s book. There, surely, a clear statement of the meaning she attaches to it should be given, but there is none. If instead we turn to Merriam-Webster, we find two definitions, the first being ‘lacking pity, kindness, or mercy’, the second ‘of or suggesting a nonhuman class of beings’. That second definition could certainly fit the branch of geology known as paleontology, which is of some interest to geographers, but that, it seems, is not what is meant by Yusoff. In that first paragraph we read that:

As diasporic human and nonhuman geographies transformed colonial spaces with labor, hoofs, creatures, and crops they also erased geologies that belonged to other imaginations of earth. These practices of “unhoming” through the epistemic dynamism of the inhuman enacted environmental changes of state in subjectification, climate, species, and elemental geophysical flows

This is, regrettably, a fair example of Yusoff’s style as an author. Her chapters are scattered with philosophical jargon words such as ‘epistemic’, she delights in the use of obscure adjectives such as ‘diasporic’, usually in places where they add nothing to the meaning of her sentences and must be included merely to sound impressive, and she uses verbs such as ‘enact’ in conjunction with subjects such as ‘practices’ that they cannot possibly have. And, a particular irritation to me, she talks about ‘geophysical flows’ while clearly not having the faintest idea about what geophysics actually is. I suspect that very few readers will persevere much beyond this paragraph, but for those who do, a theme will gradually emerge. Yusoff is blaming ‘geology’ (and, sometimes ‘geophysics’) for the exploitation of much of the world and its peoples by the European powers during the second half of the second millenium AD.

That such exploitation actually occurred, and was often brutal and always, even when relatively benign, focussed on the interests of the colonisers rather than the indigenes. Is not in doubt. The question is whether, by blaming it all on geology, Yusoff adds anything either to the study of geology or to the history of colonialism, and the answer to that has to be ‘No’. Such an answer is inevitable, given her stated belief that there was not one single science called geology, but alternative geologies that ‘belonged to other imaginations of the Earth’.

Geology, of course, has many sub-branches, all having their roots in pre-scientific observations of different properties of Earth materials and only coalescing into a single science deserving of the name in the 18th century. None of these, however, represent ‘other imaginations of the Earth. They are different facets of the one science. One of these branches is geomorphology, which is the one of most concern to most geographers but apparently not of any interest to Yusoff. The two that interest her most are what we might call economic geology, defined as the exploration for and extraction of Earth materials, and paleontology, which she likes to write as ‘pale-ontology’ because this implies a set of concepts and categories directly associated with white colonialism. These two branches have had very different histories; they did not form a single entity driving colonial expansion.

The exploitation of Earth materials is as old as man itself, in fact even older. Human beings were not the first life forms to employ rocks and stones to achieve their objectives, and there are very few human societies that have not done the same. The ancestors of today’s Europeans extracted flint from mines at Grime’s Graves, but by that time China already had a metal-working culture of astonishing sophistication, as any visitor to the museum alongside the resting place of the terracotta army outside Xi’an can testify. Europe progressed geologically from a stone age to a bronze age and then to an iron age, and by medieval times skilled miners could trade their talents across the continent. Arguably, those people were already geologists, but even if they were, it was not they nor their ore-finding expertise that spearheaded the Spanish and Portuguese colonisation of the Americas. What Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro encountered, in central and southern America respectively, were mineral industries already in existence. These they simply took over, but in the days when long-distance transport of goods relied on winds and tides, only the high-value gold and silver deposits were worth their attention. At the same time and in other parts of the world, European expansion was being fueled by desires for commodities with quite different origins. The objects of value that filled the holds of the ships of the navigators returning from the east were not minerals but tea, spices and the already worked products of civilisations far older than their own. Nor did the horrors of the Atlantic slave trade have anything to do with minerals or geology. That was a response to the need for labour on plantations of sugar and cotton in the Caribbean and North America; in a reversal of such flows, British colonisation of Australia was driven by a desire to transport some of the country’s own citizens as far away as possible. Only when steamships capable of oceanic voyagers were developed in the mid-19th century did long-distance transport of low value ores become economically feasible and commonplace. Even then, it was not for its mineral resources, which were far inland and little known, that Leopold of the Belgians wanted the Congo basin. It was for rubber and ivory,

So, if mineral resource geology had only a minor role in driving European colonial expansion, what of Yussof’s other explicit contention, that geology, or pale-ontology, was, and is, essentially racist? On pp.40-41 she wrote:

As stratigraphic concepts retrofitted the thought of racial difference as a naturalized history rather than a political geology of forms, race is conceived by Georges Cuvier (1813, 1827), Lyell (1863), Agassiz (1850a, 1850b, 1850c, 1850d), and a host of other geologists as both the process and the outcome of geologic forces.

Is there any evidence in this contorted prose for geology as inherently racist? There is no doubt that Cuvier and Agassiz were strong believers in the superiority of the white races (Lyell, less so), but was it geology that led them to it or simply the prevailing beliefs of the societies in which they lived? In her villains’ catalogue Yussof mentions neither Linnaeus, the man who brought order to biology by dividing the complexity of life on Earth into genera and species, nor Charles Darwin, who documented the evolution of species and therefore allowed others to assign to the white races the highest levels in the evolutionary process. Without their work, Europeans would no doubt still have concluded that they were superior to other races, but no pseudo-scientific case for that idea could ever have been made. Cuvier’s contribution was merely to record, before Darwin, the fact that some of the fossils he studied lacked living examples, and that therefore some species had become extinct, but he did not believe in evolution. His belief was that each species had been created to match a particular ecological niche (although he did not use that terminology), and that white mankind had been created to occupy the highest of all niches. That, certainly, is a racist view, but it was something he brought to his geological studies, not something he found there.

Meanwhile, geology was developing very much along the lines we see it following today, without reference to white supremacy,. When the French corvette Uranie left Toulon for a scientific cruise intended to take it right around the world, the ship’s medical officers, who were also the expedition’s naturalists, were provided with seven pages of instructions as to how they were to do geology. These pages would not be out of place in instructions to today’s geology students, to be delivered prior to their first serious attempts at geological mapping, and are devoted to the mapping of stratigraphy and the collection of paleontological samples. There is no mention of possible economic applications. Indeed ….

….. even if examples of new minerals are obtained as a result, these will be no substitute for the wider knowledge that these expeditions should obtain for us. The details of the lithologies are the concern of the local mineralogist, if ever those countries should offer him a home. At present and before everything, it is on the eyes of the field geologist that we rely for our knowledge of the southern hemisphere; the things that we need to know concern the nature of the rocks, considered as a whole, and the distribution and superposition of strata, and, just as these very general results are all that can reasonably be expected from such voyages, so too are they the only ones with importance commensurate with the grandeur of the enterprise. (Gaimard diary, p.58)

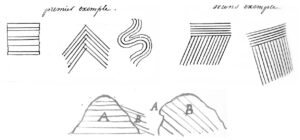

Figure 1. Sketches accompanying the geological instructions included in the diary of Joseph-Paul Gaimard, junior surgeon on the French corvette Uranie, which left Toulon in September 1817. The upper sketch, on page 88 of the diary, shows the various types of geological bed-forms and relationships that might be encountered in the field. The lower sketch, on page 89, emphasises the importance of understanding geology in three dimensions. A transcription of the diary by Sylvie Brassard can be found on the website of the State Library of Western Australia. An annotated English translation by Sylvie Brassard and John Milsom is to be published by the Hakluyt Society in the first half of 2025,

That paragraph is a far better reflection of what the science of geology is about than all of Kathryn Youssoff’s impenetrable prose. In Geologic Life she writes that ‘geology and its epistemic practices were a form of earth writing that was riven by systemic racism in the building of colonial worlds’, but all that tells us is that she has very inadequate grasp of the subject. Which is, perhaps, the reason she shrouds her arguments in the vocabulary of ontology, teleology, epistemology. To set them out in plain, universally comprehensible English would be to reveal their lack of any real substance.

And, certainly, the absence of anything that could possibly be considered ‘the Geophysics of Race’.