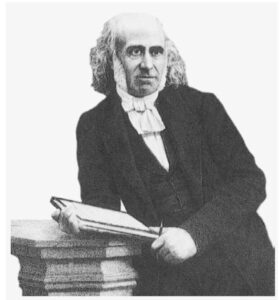

The blind Jacques Arago, towards the end of his life. A photograph, almost certainly taken by his brother François, an early enthusiast for photography. An illustration to the online biographyy of Jacques Arago by Bruno Liesen, from an original now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

In an earlier blog, I included a letter sent by Jacques Arago to Dom Pedro II, Emperor of Brazil, which had been found, almost accidentally, among the papers that Dom Pedro took with him to Portugal when he was forced to leave Brazil in 1891. The finder, David James, of Brown University on Rhode Island, published a short paper about it in 1948. in the journal The Americas. In translation the letter went as follows.

To His Majesty the Emperor of Brazil:

Many years ago, I had just completed my first voyage around the world when I received the ribbon of the Order of Christ from your august mother in Saint-Christophe. The next day I set sail for France but by a sad mischance I lost, while I was on board, the letters patent that the noble Léopoldine had given me from her own hand.

Since then my ardent curiosity has taken me to many climes, I have sailed all the oceans, studied all the archipelagos, etc. Not long ago I led to California fifty young men who, by dedicating themselves to the search for gold, will try to ensure the foundation there of a civilised colony.

Blind for twelve years, I have just accomplished the most daring enterprise in the world, and here I am again in this magnificent Brazil where you reign so gloriously and so paternally.

I would like, Sire, to see the gift that I received ratified by your Majesty and I would consider it a great favour were I to be allowed to dedicate to you the ten volumes that I am going to publish on California, Chile, Peru, Bolivia and almost all the oceanic archipelagos that I have studied with so much love.

The name that I bear assures you, Sire, of the purity of the sentiments with which the pages of my book will be filled.

Twenty-five years ago I had the happiness of offering to the Museum of Rio two heads of Zeeland kings, and I am proud to learn that they still preserve them. Today I bring a small canoe from the wild archipelago of Fiji, two brain-smashers, formidable weapons of two fierce kings of the Marquesas (Islands), a magnificent iron lance from Paioco, the most implacable enemy of Christianity, a bow and arrows from New Caledonia, where cannibalism is still honoured. I also have a large piece of fabric from Tahiti, a crown made of poi roots, woven by Queen Pomare herself, and with which I would like to pay homage to Her Majesty the Empress, your august Wife.

I have ordered that these various objects be brought down to me at the Hôtel de la Bourse, rue Alfandega, where I will await your Majesty’s orders to know the place where you wish me to deposit them.

Queen Pomare recommended me to place this crown well: Heaven has favoured me by bringing me back to Rio.

But alas, I must re-embark on Friday because I am a passenger, sent by the government, on the corvette-of-war Bayonnaise which sets sail Saturday morning without delay.

I have the honour to be, Sire, your Majesty’s very humble and very obedient servant,

JACQUES ARAGO 1 October 1850

Surprisingly, his induction into the Order of Christ was not something that Arago thought worth mentioning in the Promenade autour du Monde that he had published with almost indecent haste after the de Freycinet expedition returned to France in 1820. but since putting that blog on line, I have discovered a reference to his brief visit to Rio in 1850 in another memoir. It has the title A travers l’Amérique du Sud and was written by F. Dabadie, a man, or woman, who seems to have been very averse to revealing their first name. This covered some of the same ground as Arago’s letter, but told a very different story. The first of the two extracts below describes the offer being made by Arago, not in a letter but in person.

The conversation lasted about an hour, jumping from one subject to another, at the whim of the interlocutors. The affability of D. Pedro II had put Jacques Arago at his ease from the start, whose sallies amused the emperor, and who was delighted with his reception. As he was about to take his leave, a buffoonish idea came to his mind.

“Sire,” he said to D. Pedro, “after the excellent welcome you have honoured me with, I would want nothing if you would deign to grant me two favours.”

“Speak, I grant them to you in advance.”

“I intend,” continued Arago, “to publish the account of my voyage, and I would like to dedicate it to you. Would you be generous enough to accept this feeble tribute of my gratitude?”

“With all my heart,” replied D. Pedro.

“This is the first favour I have to ask of you; here is the second. I know that you are a lover of curiosities; I have been told of your collections, formed with infinite taste. I have the misfortune of sharing this passion, despite my poverty, and I collect objects of interest. During my stay in Nouka-Hiva, I became friends with Pa-ko-ko, that barbarian chief finally subdued, who so often led the natives in revolt against the French. Pa-ko-ko, gifted with an audacity equal to his courage, would fall upon the enemy unexpectedly, and his war-club, handled by a Herculean arm, had become the terror of our soldiers. He guarded it religiously until the hour when I left the colony; my prayers then obtained his friendship, and it is this club that I would like to offer you.”

If the emperor had been offered a sixty-carat diamond, he would not have been so pleased. His eyes shone with pleasure, his face was radiant when he replied:

“Pa-ko-ko’s war club will be the pearl of my museum. How many thanks I owe you, M. Arago!”

-“It is I who am obliged to you, since you are kind enough to accept this trivial souvenir, replied the latter in the tone of an loyal courtier.”

Then, turning to the Empress:

“T would also have a trinket for Her Majesty; but it is so insignificant that I hesitate to offer it to her”.

These words intrigued the Empress, curious as are all the daughters of Eve. She smiled graciously at Jacques and said to him:

“Let not an excess of modesty stop you. I burn to know what gift you intend for me, and I am sure that you undervalue it.”

“Oh! my God, no, because it is quite simply a crown of artificial flowers that I have from Pomare. The Queen of Tahiti made it with her fingers: this trifle has no other value.”

“So Pomaré knows how to make artificial flowers?” asked the astonished Empress.

“Badly, as you will be able to assure yourself, if you do not disdain my present.”

“No, certainly, and I am eager to have it.”

“Pomaré,” continued Arago, “received lessons from a Parisian worker, but she has hardly profited from them. I owe her this justice that, despite the vanity natural to women of her race, she does not deceive herself about her merit. She at first refused to give me a sample of her work, and I only had the crown by dint of insistence.”

“It is all the more precious”, said the Empress

Arago and Gaetano left Saint-Christophe and returned to the city.

The items were duly delivered to Dom Pedro by the consul, Felix Taunay (whose younger brother Adrien had come on board the Uranie as an extra artist in 1818), after Arago left Rio on the Bayonnaise, and for a time had pride of place in the collections of the emperor and empress. But then disaster struck. The empress looked at her gift a little more closely.

One evening, the Empress was discussing the famous crown with her ladies-in-waiting, and was studying its details minutely, when she was seen to turn pale and tremble. The ladies-in-waiting thought she was fainting; they reached out their arms to support her. The Empress pushed them away, and, throwing the crown away with force, cried out:

“The insolence!”

She was so upset that she could say no more. Her stupefied companions looked at each other in silence, not daring to try to discover the reason for the Empress’s sudden rage. The latter, ashamed of a violent action that had compromised her dignity, soon regained her composure and, addressing the ladies-in-waiting, pointed to the crown:

“See”, she said, “how foreigners we welcome here show their respect for us! Examine the inside of this crown, and decide if I deserve such humiliation.”

One of the ladies hurried to the crown, picked it up, and then dropped it in disgust after reading on it the name of Madame Dubois, a florist, at 103 Rue de Ouvidor. It was at her house that the hoaxer Jacques Arago had bought Queen Pomaré’s crown for 3,500 reis (4 francs 50 centimes), and he had not removed the store’s stamp, the sight of which caused Her Majesty’s rightful indignation.

Pedro II, informed of this discovery, shared, as one can imagine, in his wife’s anger against Arago. But what then did he think when he learned that Pa-ko-ko’s brain-smasher, as false as Pomaré’s crown, came from the shop of M. Casemajou, a dealer in bric-a-brac ! …

I believe that if he had had Jacques Arago at hand, he would have had him hanged.

What are we to make of this? The two stories agree in many details, but disagree on some vital ones. According to Dabadie, the offer was made by Arago in person, not In a letter in which many more items are mentioned, and which does not at all read as if addressed to someone already met. In that letter also, some of the items were supposedly from Fiji and New Caledonia, two places Arago never visited, and he also mentioned leaving in Rio two skulls from New Zealand on his earlier visit, twenty-five years earlier, although he never went there either. If, however, the gifts had indeed have been shown to be fraudulent, is it likely that the letter would have been preserved in the royal archives?

It is a puzzle to which there seems to be no certain answer; Arago is hardly the most reliable of sources on matters that concerned him directly, while Dabadie, in the remainder of what he wrote, showed himself to be no friend of his fellow-countryman and his information must surely have been obtained at least at second hand..

Whatever the truth, one fact does stand out. Les deux oceans, Arago’s record of his travels in 1849 and 1850, was indeed dedicated to Dom Pedro.