On the 29th of April 1820, Rose de Freycinet, uncomfortably installed in the American three-master Mercury that was making heavy weather of the transit to Montevideo, wrote in her diary that:

“I still spend part of the day in my bed. I cannot be bored because the passengers lend me English books, which I read very easily although I am far from speaking it even passably. I try to, more and more, but I often have difficulty with English idiom. Every day I find myself able to understand conversations and especially books very well but yet am very embarrassed at saying the smallest things. Among other works I have read is one by Fielding, which I find much inferior to his Tom Jones: it is similar to Roderik Random, which is also by Fielding.”

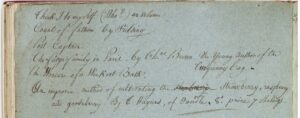

Reading this, one might well wonder what sort of books the somewhat boorish English officers would provide, but Rose herself has left a list, which the revamped Mitchell Library website has now made easily accessible. Previously the pages of her diary were viewed individually and separately, but it is now much easier to get a feel for the diary as a whole, including some pages that do not contain diary entries but which have nonetheless been digitised. One of these, Page102, which immediately precedes the beginning of Notebook 3 and which, together with blank pages 99, 100 and 101 is bound in between the two pages (98 and 103) where she unfavourably dissects the characters of those same officers, does have some writing on it, but it is not a diary entry. Instead, it is a list of books and they are all books in English (Figure 1). This surely, must be a list, not necessarily complete, of books she borrowed. Amazingly, and despite the incomplete and sometimes incorrect information that Rose provided, but thanks to the wonders of the internet, it has been possible to track down every one of these books. Transcribed, the list is as follows.

Think I to myself (Who?) un Volume

The fudge family in Paris by Th.as Brown, The Young Author of the Twopenny Bag

Rose de Freycinet’s booklist

Rose de Freycinet’s booklist

Thinks-I-To-Myself, a Serio-Ludicro, Tragico-Comico Tale, Written by Think’s-I-To-Myself, Who?

Hiding behind the Thinks-I-to-myself pseudonym, in his introduction to the Seventh Edition the author stated that as far as his identity was concerned, he had ‘never once heard it attributed to any of the Cabinet, Council or Bench of Bishops; to the Lord Mayor of London, or to Lucien Bonaparte’. He was, in fact, a clergyman called Edward Nares who, speaking as the author in that same introduction, claimed, with perfect truth, that he himself was a man whom he ‘never had the honour of meeting; having never so much as once met him in all my life; nor ever corresponded with him’. Nares life was a full one. Apart from a considerable literary output, he was, between his birth on 26 March 1762 and his death on 23 July 1841, a fellow of Merton College, Oxford; the Regius Professor of Modern History in the same university, and successively curate of St Peter-in-the-East, Oxford, rector of Biddenden and rector of New Church, Romney. Taking time out from his academic and clerical duties, he also seized an opportunity to elope with, and then marry, Lady Charlotte Spencer, the daughter of the Duke of Marlborough. Obviously a man with a strong rebellious streak, in 1832 he got into trouble with the university for declining to give his lectures. Thinks-I-to-Myself, a satirical account of the life of a country parson published in 1811, was wildly popular and ran through eight reprintings in its first year.

The Adventures of Ferdinand Count Fathom by Tobias Smollett

There might be some doubt as to whether this was the ‘Fathom’ book that Rose included in her list, since she gave the author as Henry Fielding, not Tobias Smollett. However, in the paragraph from her diary quoted above she attributed Roderick Random, also by Smollett, to Fielding, so perhaps she habitually confused the two. Despite the lack of any resemblance in their names, they are often coupled together and might even, thanks to the common practice of writing under pseudonyms, have been sometimes suspected of being the same person. The first of Smollett’s novels, Fathom is little known today but is well worth a read, even if one might agree with Rose that it is certainly not as good as Tom Jones.

The Post-Captain; or, the Wooden Walls Well Manned; Comprehending a View of Naval Society and Manners, by John Davis.

Of the six books in Rose’s list, this promised to be the most difficult to find, thanks to the existence of the book Post Captain by the much more recent Patrick O’Brian, links to which swamp links to the earlier title. It did, however, eventually surface, and the Preface to the Tenth Edition (and even the existence of a Tenth Edition) suggests that it might, in its own time, have been as popular as its successor. It might have been even more popular with some of the potential audience; the Preface begins :

“Notwihstanding the great number of naval novels which have followed in the wake of the Post-Captain, there is not one that has surpassed it in genuine sea-humour, but amidst a fleet of imitators it still wears a distinguishing pennant. Its characters are hardy tars of the true blue water breed. No marvel that the ladies fall in love with them at first sight. With an unfailing power of diffusing joy around them, they are more captivating in the laughter-loving eyes of the fair sex than Pelham or Tremaine.”

Rose might have come to a different view of the ‘hardy tars’, after two and a half years close acquaintance, but that particular edition did not appear until 1841, so she would not have read its Preface. The book was first published in 1806 and therefore, almost inevitably, includes a battle with a French frigate.

The Fudge Family in Paris by Thomas Brown the Younger, Author of the Twopenny Post Bag

Once again, Rose got the title slightly wrong. Without the author’s previous book (which satirised the Prince Regent and the aristocracy in what were supposedly intercepted letters) in front of her, she could not be expected to know the significance of the word ‘post’ in its title and she would certainly not have known that ‘Thomas Brown the Younger’ was a pseudonym used by a satirist whose real name was Thomas Moore. This was the most recently published of the books listed by Rose, having not appeared until 1818, but it was so popular that there were five printings in the first fortnight. It consists of a series of invented letters, written in verse, tracing the comic adventures and misadventures of the Fudge Family, English tourists able once again able to enjoy the pleasures of continental travel. For Rose, after dining on seals, penguins and horses for three months, some of the lines must have seemed especially poignant.

I strut to the old Café Hardy, which yet / Beats the field at a déjeuner, à la fourchette

There, Dick, what a breakfast – oh not like your ghost / of a breakfast in England, your curst tea and toast

But a sideboard, you dog, where one’s eye roves about / Like a Turk’s in the Haram, and then singles out

One’s paté of larks, just to tune up the throat / One’s small limbs of chicken, done en papillote

One’s erudite cutlets, dressed all ways but plain / Or one’s kidneys, imagine Dick, done with champagne

Then, some glasses of Beaune, to dilute or mayhap / Chambertin, which you know’s the pet tipple of NAP.

A footnote added that Chambertin was Napoleon’s favourite wine. By this time, however, according to Gaimard, the exiled emperor was enjoying regular supplies of Constantia wine, despatched every month to St Helena from the Cape.

The Wonders of a Week at Bath; In a Doggrel Address to The Hon. T. S. -, from F. T-, ESQ. of that City. by John Cam Hobhouse

Whoever it was among the English officers who provided Rose with reading matter, he seems to have had a liking for verse, because this book, like ‘Fudge’ is an account of a visit in rhyming couplets. The attractions of Bath were, however, not those of the breakfast table¸ and were presumably of less interest to Rose.

The ladies of Bath have so dashing an air / So charming a smirk, and agreeable stare

Not to say how they show all their shapes in the wind / With nothing before, and their pockets behind

Lac’d well at the head, and Iac’d well at the foot / Quite neat, and the boddice as tight as the boot

Tho’ the petticoat, once so important a charge / Clings close to the limbs, or flies off all at large

So, you know, ‘twould be foolish to sweat and to pay / To see the long legs of the girls at the play

You’ve the same sight for nothing just every day.

Rose, who was lampooned as “Madame Vertue” on Mauritius for her refusal to bare her shoulders at the Race Ball, would surely not have approved.

A Treatise on the Improved Culture of the Strawberry, Raspberry and Gooseberry … by Thomas Haynes

The last book in Rose’s list was very different, although it resembled the others in having been enthusiastically reprinted. First published in 1812, it has its followers even today. According to the preface,

“These Instructions for the Improved Culture Of the STRAWBERRY, RASPBERRY, and GOOSEBERRY, in which the natures and constitutions of these Plants are accurately considcred ; designed for the use and benefit of Families, the amusement of the Amateur, Connoisseur, and other private persons wishing to excel in the size and flavour of these fruits ; are most respectfully submitted to their candour, and the notice of the scientific Horticulturist, in full confidence that where a due regard is paid to the directions offered, their attention will uniformly be rewarded with ample crops of superior fruit. “

It may have been comforting reading for someone such as Rose, looking forward to a return to domesticity, but it is less easy to imagine why an army officer on his way to join a revolution should choose to take it with him.