In a long and rambling essay that Jacques Arago contributed to the short-lived but high-profile Le Livre des Cent-et-un, he included the following exchange in a Paris salon:

“Your name?”

“Arago.”

“Arago. Are you brother of the famous one?”

“It is I who am the famous one.”

Jacques Arago in 1939, by which time he was completely blind. Portrait by Nicholas Eustache Maurin, now the property of the National Library of Australia.

And, despite his brother François being one of France’s most renowned scientists and a man who would become, much later and very briefly, the country’s head of state, at the time Jacques made this statement it might very well have been true. His initial account of the voyage of the corvette Uranie (he wrote many others) had been wildly popular and had been translated into both English and Spanish, and he was making a name for himself as an essayist and dramatist. Perhaps neither brother is now remembered as well as they deserve, but of the two it is François whose reputation has survived the best. Search for Arago on the internet and it is he to whom references appear first and in the greatest number. Jacques, it seems, has been the subject of just one book-length biography, and the various short ones that can be found on line, such as the Bruno Liesen’s ‘Jacques Arago’, the l’abbé Capeille’s 1914 Dictionnaire de biographies roussillonnaises and the Wikipedia entry (as of 5 October 2024), contain curious omissions. All of them focus primarily on the voyage of the Uranie, and to a lesser extent on his literary career in the 1830s, none of them mention his detention in the 1820s in Esprit Blanche’s mental hospital in Paris, and only Liesen cites the three-volume Les Deux Océans, an account of his second major journey, which began with a plan to go looking for gold.

It sounds an improbable project. Is the Deux Océans even believable ? To believe it, it is necessary to believe that an already quite elderly, and very definitely blind, man, hearing news of the discovery of gold in California, had been able to assemble a group of fifty younger men to join with him in an expedition to go there and make their fortunes. And that in doing this he was the first off the mark, when quite a number of French adventurers had had the same idea. And that when, for multiple reasons, the association disintegrated in Valparaiso, instead of getting the first boat back to France, he took passage on a ship headed for the Marquesas and then Tahiti, where he chatted with its queen, Pōmare IV, who had just been forced to transform her islands into a French protectorate, before taking passage in the French corvette Bayonnaise that happened to be visiting Papete on its way back to France from a diplomatic mission to China and bringing with him to Rio a range of artefacts from the South Seas as gifts for the Brazilian emperor, Dom Pedro II.

Pull the other one, one might say.

Or, at least one should seek confirmation. Are there independent testimonies?

We can begin with a memoir of the life of Alphonse Antoine Delépine, who was born in Paris on the 4th of March 1823, written by his daughter Mathilde. Concerning Jacques, she wrote:

“In 1848 Jacques Arago formed a company of speculators and left for California. My father was a member of that company. From father’s mss. we find the company left Le Havre March 1848 on the three-masted boat L’Edouard under Captain Curet. Four months later they arrived at Valparaiso Chile. Later the arrival in San Francisco with Curet as Captain.”.

The 1848 date, although written twice, must surely be a mistake, because the existence of rich gold placer deposits in California’s Sacramento Valley did not become public knowledge until it was revealed in the New York Herald in August 1848, and it would have taken some weeks for the news to cross the Atlantic. Moreover, France was in the throes of a revolution, in which François Arago was a prominent figure; it would have been difficult to form and equip an expedition under thos circumstances.

Independently of the daughter’s memoir, Delépine’s first-person account of the expedition was one of the sources cited by Malcolm Rohrbrough in his history of the associations of Frenchmen who joined with the other ‘49ers’ in the gold rush. On pp.62-63 of the Rush to Gold he wrote of these associations that:

Of all the small, select companies, the most recognizable name and the most public voyage was that associated with Jacques Arago, the head of a company of young Parisian gold seekers. Arago was a prominent man of letters, an eminent traveler who had lost his sight in an accident. Now, blind and sixty-four years of age, he proposed to found a company “to exploit the golden placers of the modern El Dorado.” Riding the burst of enthusiasm for California and its gold, Arago mounted his own expedition to San Francisco in the ship Édouard. His company departed Le Havre on March 30 on a voyage that would be characterized by discord among the passengers and conflict with the captain.

The most complete account of the voyage was left by Alphonse Antoine Délepine, an original member of the Jacques Arago Company. Délepine began his recitation by noting the clothing and equipment specified in the company’s contract: “Each member will provide himself with an outfit: six shirts, three pairs of shoes, two jerseys, two pairs of pants, two smocks, a felt hat, a leather belt, a military kit-bag, bedding, a set of metal dishes, the whole in good condition. Each member will own the following weapons: a brace of pistols and a two-barrel gun, ammunition, and a long dagger. Each member will have to buy his own ticket and pay for the freight of his goods taken by him on the ship, the ‘Édouard,’ at present in Havre and ready to leave sometime the coming March.

Arago’s company, the Société Parisienne, later better known as “Arago’s Company,” was composed of a broad range of participants. Délepine’s list included, among others, four “artists” (one was a pianist), an engraver, four laborers, three clerks, six manufacturers (of watches, jewelry, and hats, among other items), a house painter, a peasant, a distiller, a doctor, a lawyer, an accountant, six men of independent wealth, three landowners, and “a man of letters” (Arago himself). Taken as a whole, his company had a large proportion of men from good families, with respectable professions, and a majority of young men. Délepine identified forty-three members, “young men for the most part filled with fire and ardor.” The whole group was well armed and supplied with six months of provisions to support the stay in California. The members of the company swore allegiance to one another in a banquet before departing Paris. They journeyed to Le Havre, where they awaited departure with “impatience mixed with emotion.”

Of the scores of companies that eventually emerged into the light of day, perhaps no other was so intensely associated with a single individual. Arago was a charismatic leader who generated feelings of devotion and almost veneration. Members of the group spoke of him as “our chief,” “this new Jason,” and “this other Belizaire” and referred to themselves collectively as the “Argonauts of Arago.” This intense personal identification would be important in retaining the identity and morale of the group over a long voyage and in the face of many frustrations.

The difficulties aboard ship reflected a growing division between Arago and the captain of the Édouard. When the ship reached Valparaiso, Captain Curet disembarked the Arago Company, declaring that his ship would remain in port for three months instead of the customary fifteen days. His intention was to embarrass Arago, who had promised a prompt voyage to his company. Eventually, most of the Arago Company would part from their leader in Valparaiso and proceed to San Francisco without him. Arago wrote with some bitterness that his “companions on the voyage abandoned him in Chile.” It was an unhappy ending to a very personal undertaking, yet the dissolution of the Arago Company would be duplicated by almost every other “California company” on landing in California.

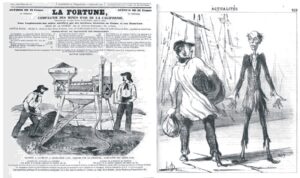

Two of the contemporary illudtrations reproduced in Malcolm Rohrbrough’s ‘Rush for Gold’. On the left, an advertisement that appeared in the Charivari on June 25, 1850, showing well-fed and well-dressed workers operating a sluice. On the right, a more realistic appreciation of the gold rush by Honoré Daumier, showing a meeting between a new arrival and a ‘miner’ after a few months in the Sacramento Valley.

Other Frenchmen quickly followed Arago’s lead, and among them was Charles de Lambertie who, in his Voyage pittoresque du Californie et au Chili, described his meetings with Arago in Valparaiso on his way to the goldfields

It was in a store where I had gone on business that I had an encounter that gave me some pleasure; I mean with M. Jacques Arago. I knew that he was in Valparaiso and I intended to pay him a visit, in my dual capacity as a Frenchman and a man of letters, when I was introduced to him at the moment when I least expected it. It is known that M. Jacques Arago had organized a company to exploit the gold mines of California; this mutual association, which I believe was called the Parisienne, left Le Havre at the end of March or April on the Jeune Edouard. We have all seen the farewell letter, so well written, that M. Jacques Arago had printed in a newspaper at the time of his departure. He had left five or six months before me, and I was very astonished to meet him again in Valparaiso. He then told me that his hard-working partners, who at first were very respectful to him, later became considerably lax. Idleness led them to gambling during the crossing; at first they hid it from him; then later, not only did they no longer hide it, but when he wanted to make some comments to them, they sent him packing. The hierarchy was thus already almost destroyed. In short, they arrived at Valparaiso, where the ship remained for two months, and during this long break, bad news was received from California. Several of the partners, who were happy in Valparaiso, did not want to go any further, and those who continued their voyage begged their director not to continue to California. According to them, things there were going too badly for him to risk landing there. Finally, after much insistence, he decided to stay behind, although with great regret, for he was still thinking of going to this Eldorado, where some people have been lucky and many have been unlucky.

It was precisely through one of the partners of the Parisienne, who had remained in Valparaiso, that I was introduced to M. Arago. Seeing the fate of this company, I thought of ours, the Espérance company, and I learned that all companies disbanded as soon as they set foot on Californian soil. There are, moreover, very few reliable ones, and most of them load on merchandise when the ship leaves France without paying anything, so the captain finds himself obliged to sell it to pay for the freight and the passage of the partners and there is nothing left for the company on arrival, neither food nor money. These are, in a word, speculations which seem to me to be created only to obtain money, with which one can have many goods, by paying only half in cash. People will do well, in the future, to be wary of this kind of enterprise, in which so many have been cheated.

A few moments after my meeting with M. Arago, he offered me his box, to go to the theatre, to attend a rehearsal of some young French people, who proposed to give a vocal and instrumental concert. I then saw the performance hall which seemed to me larger and more beautiful than I would have hoped for, in this remote corner of the world. The backdrop on show was a very ingenious allegory and very well suited to the occasion. It showed the nine muses, each in her own special role. In one corner of the painting, the muse of history could be seen holding by the hand a savage American, armed with a bow and a quiver full of arrows, and seeking to initiate him into the enchanting mysteries of civilization. He seemed to be in ecstasy before the magnificence of the monuments of the civilized world. Although this canvas is not a very finished work, one must pay homage to the idea, which seemed to me admirable in its finesse and poetry.

The auditorium is almost oval; it is arranged as are those of Europe and on four floors. The galleries of the boxes are decorated with paper in very good taste, and with a very pleasant effect onthe eye. M. Arago having done me the honour of offering me his box, whenever there was a performance, I took advantage of his invitation one Sunday when they were performing “El hombre mas feo de Francia” (The ugliest man in France). They have a strange method with tickets in Valparaiso. Those that you buy at the door, for 4 reals, only give you admission, and you can only go then to the stalls or to the uppermost gallery; the prices are nevertheless different for these two places. If you want to go to a box, you have to pay extra once you are inside the theatre.

The Ugliest Man in France, the Spanish comedy presented that evening, was quite well played by the company. The hero of the play was the famous courtier, the Duc de Roquelaure. There were many people at this performance and quite a large number of ladies. After the play there was a ballet in which some Spanish dances were performed in a pas de trois. These dancers, who were all the rage in Valparaiso, seemed to me a little ponderous and would not have had the same success in the cities of France.

I still have to mention a concert given by two passengers of the Succès. One of them was a fairly accomplished flautist and was going to perform at the Théâtre des Variétés in Bordeaux and in the philharmonic societies, and the other was second bass singer at the grand theatre in the same city. They were joined, as amateurs, by two other young people who were also on board our ship. None of this prevented them from being subjected to very severe, I would even say insulting, criticism. An article appeared the next day in El Mercurio, where people expressed themselves very harshly towards them. This furious attack generally upset them, and M. Arago, in a reply which he had published in French and Spanish in El Comercio, observed to them, with great propriety, that the domain of criticism did not extend to insult, and that it only reflected on the one who made use of it.

At the same time, they were busy with the rehearsals of a play by M. J. Arago, entitled La Carcajada, (The Gale of Laughter), which had been successfully performed in Paris. It was performed on the day of our departure from Valparaiso, that is to say on Thursday, January 17, in a benefit performance. M. Arago, who was at first living at the French consulate, had been at the Hôtel du Chili for a few days, having been obliged to give up his apartment to the consul general, who was expected daily in Valparaiso.

Jacques never mentioned any meetings with de Lambertie but there is no reason to suppose that the latter’s account is a fabrication. Unable to go to the goldfields, he would have seemed to have had only two options. He could either remain in Valparaiso, where he seemed to be establishing himself in theatrical circles and might have been able to make a living, or he could return to France. He, however, found a third way; he took passage on a ship called the Ana, which had possibly been bought by France to service the island colonies it was establishing in the eastern Pacific, and sailed with her to the Marquesas and then to Tahiti. Fortuitously, while he was on Tahiti the French corvetter Bayonnaise called there and he was able to take passage on her back to France.

After leaving Tahiti, the Bayonnaise stopped only once before reaching France, and that was in Rio de Janeiro, where Jacques wrote a letter to Dom Pedro which was remarkable for the absence of any hint of his avowed republican sympathies. It was almost certainly ignored and unanswered, but it went with Dom Pedro’s other papers to Portugal when he was forced to leave Brazil a few years later, and was found there almost accidentally by David James, who published a short paper about it in the journal The Americas. In translation, it went as follows.

To His Majesty the Emperor of Brazil:

Many years ago, I had just completed my first voyage around the world when I received from your august mother in Saint-Christophe the ribbon of the Order of Christ. The next day I set sail for France but by a sad mischance I lost on board the patent that the noble Léopoldine had given me from her own hand.

Since then my ardent curiosity has taken me to many climes, I have sailed all the oceans, studied all the archipelagos, etc. Not long ago I led to California fifty young men who, by dedicating themselves to the search for gold, will try to ensure the foundation there of a civilised colony.

Blind for twelve years, I have just accomplished the most daring enterprise in the world, and here I am again in this magnificent Brazil where you reign so gloriously and so paternally.

I would like, Sire, to see the gift that I have received ratified by your Majesty and I would consider it as great a favour were I to be allowed to dedicate to you the ten volumes that I am going to publish on California, Chile, Peru, Bolivia and almost all the oceanic archipelagos that I have studied with so much love.

The name that I bear assures you, Sire, of the purity of the sentiments with which the pages of my book will be filled.

Thwenty-five years agoI had the happiness of offering to the Museum of Rio two heads of Zeeland kings, and I am proud to learn that they still preserve them. Today I bring a small canoe from the wild archipelago of Fiji, two brain-smashers, formidable weapons of two fierce kings of the Marquesas (Islands), a magnificent iron lance from Paioco, the most implacable enemy of Christianity, a bow and arrows from New Caledonia where cannibalism is still honoured. I also have a large piece of fabric from Tahiti, a crown made of poi roots, woven by Queen Pomare herself, and with which I would like to pay homage to Her Majesty the Empress, your august Wife.

I have ordered that these various objects be brought down to me at the Hôtel de la Bourse, rue Alfandega, where I will await your Majesty’s orders to know the place where you wish me to deposit them.

Queen Pomare recommended me to place this crown well: Heaven has favored me by bringing me back to Rio.

But alas, I must re-embark on Friday because I am a passenger, sent by the government, on the war corvette Bayonnaise which sets sail Saturday morning without delay.

I have the honor to be, Sire, your Majesty’s very humble and very obedient servant,

JACQUES ARAGO 1 October 1850

The Bayonnaise was indeed in Rio on that date so, even though its captain, Edmond Jurien de la Graviere* did not mention either taking on a passenger in Tahiti** or presence of such a well-known person on board, his account, in the third volume of his Voyage en Chine. of the last stages of his voyage can be considered circumstantial confirmation of the bare outlines of the tale told in the Deux Océans.

Why, then, has this seemingly surprising and fascinating story been so neglected?

Perhaps this was because its author failed to make it fascinating. By this time all Jaques’s failings as a raconteur, foreshadowed in the Promenade and becoming more and more prominent in his later work, had taken over completely. While it was inevitable that a man who was blind would have less to say about his surroundings than one who could actually see them, it did not have to be so much less; the details of the interactions amongst the Aragonauts and the conflicts between Jacques and the captain of the Edouard are lost in a welter of philosophical and historical musings. It is only in what is effectively an appendix that, stung by much-publicised criticisms of his conduct and his actions, Jacques provided some readable details, by reproducing a number of letters. Here we gain a clearer insight into the expedition, in a chapter that, thanks to Jacques’ style of writing , poses many problems for the translator but is well worth presenting in full.

WHAT HAS BECOME OF THEM?

Captain Curet.- Exhibits for the case.- Letter from Jacques Arago to his dear Aragonauts. – Their reply. – My letters to the newspapers. – The Edouard is sold – I am waiting for a letter.

Even today, when I cross a street or walk along aboulevard, many people approach me, and, referring to those who had named me their president at the beginning of the expedition, they ask me this question: What has become of them? Well. gentlemen, they are out there, scattered from the suburbs to California, from Brazil to China, from Valparaiso to the Rocky Mountains.

You will understand perfectly well that having lived so long among these men, I could not deceive myself about them; but I did not think that the dissolution would begin even before we reached California …

You will have seen, from the start of this book, that an odious accusation, directed against me by Captain Curet, had alarmed those who were hoping for my return. The ridiculous pamphlet which depicted me as the head of a vast conspiracy, and presented me and my traveling companions as armed to the teeth and ready to tear each other apart, was published in Brest, Cherbourg, Le Havre, Paris and Bordeaux. … Here are the newspapers of Valparaiso that published my reply, from which I took away only the testimonies of the liveliest sympathy with which the editors of these papers accompanied my farewells.

JACQUES ARAGO .Valparaiso, 2 October 1849.

LETTER FROM JACQUES ARAGO TO HIS DEAR ARAGONAUTS

The painful farewells have just been said. My traveling companions, whose fatigues and perils I was to share, no longer wish me to accompany them to the goldfields, fearful of my exhausted strength and greatly alarmed by the news from San Francisco. We are leaving each other. Alone they will face again the fury of the ocean, the doldrums of the equator, the sharp squalls of the north, I will no longer take part with them in their conversations or share their emotions… and, when a storm roars around me, I will think I see their ship sinking beneath the foaming wave, and hear their last sighs drowned in the fatal eddies.

Yes, as heaven is my witness, I wished for half of their sorrows much more than half of their joy.

I am advanced in years, and it is understood that if I still pursue fortune, it is only for the tender memories I leave behind me.

All my Aragonauts left with dreams of gold, with both hands thrust into the bowels of the earth, for a year so rudely lacerated, all returned, buying in advance houses, palaces, estates, a kingdom! …

Courage then, my friends, courage and unity! … There is your present, your future, there is your security; there are forty of you, endeavour, if you want complete happiness for the poor Belisarius who greets you with his hand and with his eyes full of tears, that not a single one of you avoids duty’s call,.

What is saddest in this is the separation; what is most consoling is the return; ever-traveling thought will bring us together before the time fixed for the ending of the work; we will exchange, even when absent, those sweet and holy words that speak of fraternity, and the blind and the sighted will be separated only for a more lively joy.

So, I do not say farewell to my Aragonauts, but au revoir.

JACQUES ARAGO. Valparaiso, October 2, 1849.

THE ARAGONAUTS, Valparaiso , 4 October 1849.

FRIENDS TO THEIR FRIEND, THE ARAGONAUTS TO M. JACQUES ARAGO .

“It is with pride and pain at the same time that we read in the newspapers the expression of your feelings towards us .

Yes , M. Arago , the latest news from California moved us and, faced with the drama which is unfolding and in which we are going to take such an active part, we have, in spite of ourselves, been forced to open our eyes and see how much we would, by taking you away, be imperilling the life of a man whose name is one of the glories of the fatherland.

Yes , M. Arago , we believe we are doing our duty in opposing danger with prudence.

You will remain, sir, you will not suffer the greatest misfortunes that we have to fear. Matters in California have changed since our departure from France, difficulties have become impossibilities, and when one wishes to preserve one’s flagship, one does not expose it imprudently. Nearby, as from afar, here as in San Francisco, your interests will be ours, your name will be our totem, and, whatever happens, sir, the hearts that beat in our breasts will always be worthy of your esteem and your affection.

THE ARAGONAUTS. Valparaiso, October 4, 1849.

What is left, after that, to Mr. Curet’s lightning volleys? You see, they made merely a noise but struck no one. Only we remained standing. On his side only Captain Curet remained. However, on my arrival in Paris, I sought here and there for the trail of my adversary… Alas! I learned that he was still on the banks of the Sacramento, you will see later in what state, and I had to be content with sending him a few copies of the letter published by me at that time in several newspapers of the capital… Here it is.

JACQUES ARAGO Paris, December 31, 1850.

You were kind enough, my friends, to announce, two years ago, my departure for California; the enclosed letter will tell of my return to those who still remember the wandering Belisarius, and will give them some preliminary explanations on a certain pamphlet launched against me and the men I led to San Francisco.

Gentlemen and dear colleagues, here I am ready to revive the fight so imprudently provoked by Captain Curet. I arrive a little late, I admit; but the winds have their caprices, and I have had time to shape myself to the shock of the waves, the bellows of the gusts and the whippings of the downpour, quite familiar guests of my adventurous life.

From a distance one can hardly hear oneself, the voice of the waves drowns out that of man, and I was four thousand leagues from you when I was read the formidable pamphlet of the captain of the Edouard.

Already, I know, the French consul in Valparaiso and our chargé d’affaires in Chile, MM. Blanchard and Cazotte, have addressed their complaints to the ministers of the Republic; they did so with that frankness and loyalty of character which earned them general esteem, and here am I, the head of the horrible plot, armed from head to toe to assign to each his place and nail the slanderers to the pillory.

Procès-verbaux of the facts and gestures of Captain Curet have been drawn up in due time and place, and have been deposited in safe hands. They will see the light of day.

As for me, whom M. Curet did not fear to accuse of cowardice, when of my own free will I climbed the Cordilleras and sailed the Oceans; as for me, who return with furrowed brow but no furrows in my heart, it seemed to me right not to see my home again as long as my traveling companions struggled for the nuggets of Californian. Rich in the memories of my past, I wanted to visit again those beloved archipelagos where I had almost served as forage for the elegant islanders of the Pacific, and those where I rocked myself with so much love in all the winds.

I wanted to compare age to age, and I pen a book, more true perhaps, more curious for sure, than the one I would have written if the sun had not ceased to shine on my extinguished pupils.

I ask your indulgence for the book, I want from you only your impartiality in reporting the debates that were begun in my absence and which will end in opposition, as they say in the palace.

Will you not, gentlemen, give space to these lines?

Thank you, in advance, thank you, and a heartfelt greeting.

JACQUES ARAGO

So, on my return as on my departure, my life was perfectly in order. You have the papers of the case, you can comment on it with full knowledge of the facts.

The Edouard was sold in San Francisco, they also sold my linen, my wines, my secretly carried objects of exchange; I received the news in Tahiti, that is all that was sent to me: a letter of a few lines only.

Before my travelling companions and I addressed to each other our farewells in Valparaiso, a formal document was signed by which it was stated that the forty-fifth part of the profits that the Company would make would be sent to me by our consular agent in California … What has become of the Aragonauts?

Even if many of them live there from hand to mouth, sometimes anxious for the future, I also know some who are building a brilliant fortune there …

What has become of them, and of the others?

The path from here to Sacramento, via Panama, is trsvelled quickly and without difficulty, the caravans of both worlds criss-cross it incessantly, the ships anchored at Chagres wait for ballast. A letter is soon written, it takes up little space, it says that one remembers the past… it calls for a smile on the lips, it is always received like a beloved visitor…

Come, come, a letter is not a nugget, let it cross the Atlantic, and let me finally give a precise answer to those who still ask me this question.

What has become of them?

And there, perhaps, if we are wise, we should leave Jacques, as he prepares for his final voyage. In 1856 he went again to Rio, where he died, some say while staying with his friend, the actor João Caetano, others while he was descending the gangplank and before he even set foot ashore.

- * After this blog was first posted, Suzanne Falkiner wrote in to point out that Jacques may already have known de La Graviere, because on the 15th of August 1820 Rose de Freycinet recorded the arrival in Rio of three vessels of a French fleet under the command of his father, Pierre Roche Jurien. Louis de Freycinet went on board to pay his respects, and on the 15th, St Louis’ day, he attended a dinner given for his senior officers.

- ** Suzanne Falkiner also noted that news of Jacques’s escapade reached Australia, even though he did not go near it. On p.5 of the Launceston Examiner for Saturday 26 April 1851 there was a note to the effect that “The corvette, the Bayonnaise, which for some time was in the Chinese Seas, arrived at Cherbourg on the 6th December. At Tahiti it took on board M. Jacques Arago, the blind traveller and author, who last year went out to California at the head of a band of gold diggers.”