Sometimes being on LinkedIn is really worthwhile. If I had not been, and had not sighted a post by Felipe Santos, I might never have been aware of the existence of the 2024 Bouguer gravity map of the whole of Brazil. And that would have been a pity.

Brazil is, of course, a very big place. Somewhat smaller than the US but somewhat larger than Australia, it is a great place to look at gravity variations on a continental scale. And, like Australia, it has the great virtue (from a gravity user’s point of view) of being fairly flat, so that Bouguer corrections are generally small and in many areas terrain effects can be ignored.

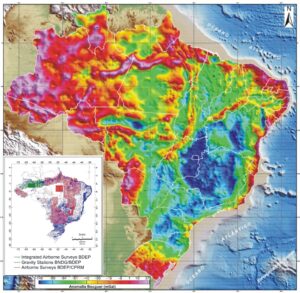

Figure 1. Bouguer gravity map of Brazil, 2024. The inset shows data distribution. The processing is described in ‘New Free-air and Bouguer Gravity Anomalies Maps of Brazil’ (Roberto P. Zanon dos Santos, Yára R. Marangoni, Carlos A. Moreno Chaves, and Giuliano S. Marotta, 2022).

Some things jump out of the map almost at first sight, and one of these is the narrow and almost linear gravity high that roughly coincides with the main course of the middle Amazon in the far north of the country. What is surprising is that this feature seems to have attracted much less attention than it deserves. One would think that it would be worth at least a mention in a paper with the title ‘Tectonics and paleogeography along the Amazon river’, but there is none. Indeed, in one place there is a statement that appears incompatible its existence. The authors state that:-

The available data are insufficient to put forward kinematic interpretations but, considering the trend of the dolerite dykes, it could be suggested that the structures of the Amazonas Basin are closely associated with a WNW- trending extensional axis. The existence of transcurrent faults running parallel to the extensional axis and working as transfer faults, which controlled the orientation of the major rivers of the paleodrainage systems, could also be assumed.

If the basin did, in fact, extend along an axis that trended WNW, then the trend of the gravity high, which is clear evidence for the presence at depth of a narrow zone of high-density rock trending a few degrees south of west, is inexplicable, and all the more so because the effects of this body can be seen also on the magnetic map of Brazil. In the magnetics, though, it has to be searched for amongst the much more intense anomalies associated with the basement rocks that outcrop on either side of the basin.

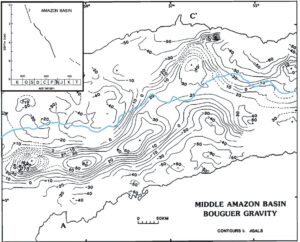

Figure 2. Bouguer gravity of the Middle Amazon Basin, modified from ‘Gravity anomalies and Flexure of the Lithosphere at the Middle Amazon Basin, Brazil’ by Jeffrey A. Nunn and Jose R. Aires (1988). The inset, plotting the timing of basin subsidence, is from from the same publication and shows subsidence concentrated, and almost uniform, from the Ordovician to the Permian. The irregular black lines are the boundaries of the outcrops of basement rocks to north and south, and the blue line provides an indication of the course of the Amazon river.

It is not that the gravity anomaly is either new or uninterpreted. The task was undertaken more than thirty years ago by Jeff Nunn and Jose Aires, who provided models that took into account both the Bouguer gravity anomalies and the available information from seismic refraction and reflection surveys, as well as the geological data from some sixty deep wells. A history extending back into the Cambrian was documented, and a very large mass of dense rock was interpreted as having intruded and replaced the lower crust over an irregular zone with the ENE trend. The geological control suggested that rifting and intrusion took place in the Ordovician or slightly earlier, with subsidence over a wider area in response to the load continuing into the Permian, at which time the point was reached at which the load could be supported by crustal rigidity. The entire process of rift formation and major rift-related subsidence thus predates the formation of the modern Andes in the Cretaceous, implying that the present-day drainage pattern was established in the context of earlier orogenies at the western margin of continental South America. The gravity feature terminates rather abruptly just west of the western limit of the area shown in Figure 2, and it is tempting to associate that with the appearance in Figure 1 of a somewhat similar but more diffuse feature coinciding with the Pantanal Setentrional wetlands further north (Rossetti, Molina and Cremon, 20i6). That, however, is pure speculation.

It is nice to find, in a study now more than thirty-five years old, the full armoury of geological and geophysical information deployed to further our understanding of the evolution of one of the world’s most important rivers, but disheartening to witness the virtual abandonment of that integrated approach in more recent publication.