One thing I didn’t anticipate when I decided to look at the role played by a railway in Ayn Rand’s “Atlas Shrugged” was that only a few weeks later the UK would be facing something of a rail crisis of its own. Cracks have been found in the chassis sections of the Hitach 800 high-speed trains operated by Great Western Railways, London North Eastern Railway, Hull Trains and also on what is laughingly known as the Trans-Pennine Express. This is almost a re-run of a problem that surfaced in early April, when cracks were discovered in the yaw damper bolster of these same trains. Now cracks are being found in the chassis units of the same trains. What, one wonders, would Dagny Taggart have done?

And, one wonders, what would she have done had cracks been discovered in any of the multiple items, including rails and bridges, that were built of the new Rearden wonder metal, in which she had invested so much of her time, energy and reputation. She had ridden roughshod over those who suggested that there might be safety issues with this untried material. If Eddie Willers had come to her and reported hair-line cracks in the new rails, would she have been woman enough to admit that she might, perhaps, have been a little too hasty?

Dagny, it is very clear, was not responsible for the (fictional) disaster in the Winston tunnel, but it had something of her style about it. The sequence of events leading up to it are lovingly described in “Atlas Shrugged”, and it could be convincingly argued that the ultimate cause lay in just the sort of ‘can-do, brook no obstacles’ sort of approach that was very much part of her management style. But, it was not her but a drunken braggart of an engine driver who volunteered to take the Comet through the tunnel.

However, according to Rand, it was not the driver who was the real cause. It was all the fault of the passengers. In Car No 1 we were introduced to a sociology professor who believed that all individual effort was futile and could make no difference. A very rare bird, and ultimately a rather pathetic one, because whatever else might be said or not said about the causes of his death, it is very clear that individual decisions played a very considerable part in it. The man in Car No 2 was a much more convincing hate figure. He was:

……. a journalist who wrote that it is proper and moral to use compulsion “for a good cause,” who believed that he had the right to unleash physical force upon others — to wreck lives, throttle ambitions, strangle desires, violate convictions, to imprison, to despoil, to murder — for the sake of whatever he chose to consider as his own idea of “a good cause”…

Yes, indeed. Journalists of a type have certainly existed, and exist down to the present day. They have come from both the far right and from the far left. One has only to look at the Nazi’s own paper, Der Stürmer, to see where that can lead.

A front page of ‘Der Stürmer‘. We all know what followed

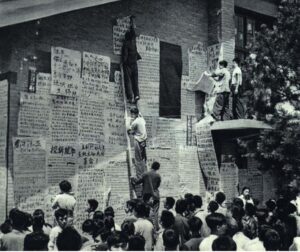

A few years after “Atlas Shrugged” was first published, the cultural revolution in China had its own fanatics. The Beijing students with their big sheets and paste pots might not, perhaps, be considered journalists proper, but they were in the same tradition. Millions died.

Beijing University students with their ‘big character newspapers’ during the cultural revolution.

Even in our ‘liberal democracy’ the mainstream papers have had their merchants of hate. We have had our Katie Hopkins, with her “refugees as cockroaches” trope. Perhaps asphyxiation in the Winston tunnel was a fitting end for the man in Car No. 2, but if it was, was it then also a suitable end for a man who believed in futility? Does the same punishment fit these two very different crimes?

And there is another problem. The people who would revel in the death of such a journalist are not, in reality, any great distance from sharing his views. John Galt may not have shown any strong desire to imprison, to despoil, and to murder, but he certainly set out quite deliberately “to wreck lives, throttle ambitions, strangle desires, violate convictions,— for the sake of what he chose to consider as his own idea of “a good cause”. He did not simply choose to withdraw his own labour from a system that he found intolerable, he embarked on a long-running campaign to persuade others to do the same. Not only was he fully aware of the wreckage and misery that would be the consequence if he was successful, he gloried in it. As Francisco d’Anconia told Dagny Taggart, he had said “when we would see the lights of New York go out, we would know that our job is done.” That was his nihilist vision, alongside which Danneskjöld’s thuggish attacks on aid shipments seem almost acceptable.

There is a bizarre conjunction in the fact that the problems with the Hitachi 800 stem from metal fatigue. In my (very much) younger days there was another Comet involved in disasters. That one was an airliner, and in fact, after the problems were recognised, understood and dealt with, I flew to Australia in an improved model. But the earlier versions? The gung ho mentality had much to do with those failures. Four and a half years before the first publication of Atlas Shrugged, one of the British Overseas Airways Corporation fleet of De Havilland Comets, the world’s first ever commercial jet airliner, took off from the airport that served Kolkata. Six minutes later, it crashed in flames. The crash was blamed on bad weather and the Comet’s continued to fly. Six months later, another went down in the sea near the island of Elba. There was a little hesitation this time, but the regulators declined to act and the Comets were back in service a little over two months later. It took just two weeks for a third Comet to be lost, not far from the site of the second crash.

At least we have moved on a little. Boeing was allowed only two crashes of the 737 Max before the planes were grounded. Congress can still make laws that abridge the freedom of production and trade, in a way that was anathema to Judge Narragansett, although, as the clearance of the aircraft to fly into trouble once again might suggest, those laws might not be implemented rigorously enough. But, one tantalizing question remains. Did Ayn Rand name the flagship of the Taggart rail fleet the Comet in memory of those 1950s disasters? And, if so, who did she blame for them? Or was she simply unaware of them, as she was seemingly unaware that, even in 1957, in the real world an already flourishing civil aviation industry was already eating into Dagny’s customer base?