Paris, ou le livre des cent-et-un was a short-lived literary journal published in just 15 issues in the first half of the 1830s. Its origin was remarkable. It is said that a number of writers decided to come to the aid of the bookseller Ladvocat, who was in financial difficulties, by giving him articles for publication in the journal (which was originally to be called The Lame Devil in Paris or Paris and Morals as They Are). Jacques Arago made three lengthy contributions, with the Chevaliers d’Industrie appearing in Volume 10. The literal translation, ‘knights of Industry’, does not give any real indication of the subject matter, which concerns the number and success of fraudsters and con-men in Paris under the restored monarchy, . I have used ‘cavalier’, with its connotations of someone who is ‘cavalier’ in his dealings with others, wherever necessary.

A longish contribution, the article falls readily into two parts, of which the first deals with Jacques’s two encounters with a beggar who was rather definitely not a ‘chevalier’ of any sort and whose parlous condition would be contrasted, in the second part (which will appear in translation later in this blog series) with the success of those who triumphed by their dishonesty.

Arago was at the time living with his eldest brother, François, and quite possibly one or more other brothers, at the Paris observatory, where François had accommodation by virtue of his position. It is an interesting exercise to trace the routes Jacques took through the street of Paris to get there.

He began his tirade with a description of what it meant to be a ‘Chevalier d’Industrie’:

It is a profession, like tinsmith, tailor, print dealer, horse trader, or man of letters.

To live from day to day, no matter how, is a motto so widespread among us that when, from my wide window, I cast a glance into the street, I shrug my shoulders and smile with pity at the sight of those sincere tips of the hat, those eager handshakes, those deep curtsies, with which those who come and go meet and part.

I spoke of curtsies, did I not? It is said that there are also, throughout the world, female cavaliers for whom no technical word has yet been created, so much are women privileged in everything. Or is it rather that, because the dictionary of our language was created and owned by men, to whom it seemed ungallant to attribute such an odious vice to the weak beings to whom, according to both religion and morality, which are in agreement on this matter, we owe both aid and protection?

So it is that, whether from selfishness or politeness, we do not want there to be either young girls or elderly mothers among the cavaliers. Why should I be more severe than Boiste’s Dictionary or the Dictionary of the Academy? And when, moreover, have I been the victim of cavaliers in cornets, wimples or lace dresses? And, all things considered, would not my first assertion be a slander against a sex already too subject to the power of men? Poor women! Another enemy to fight! Another cowardly accusation to defeat! Peace, ladies! I was in a foul mood when I was writing just now. I accuse myself, I beg for mercy, and I recognize, with you, that he has no slight fault with which to reproach himself who, in drawing your portrait, sees anything other than a constancy in misfortune that we know not how to appreciate and a courage in adversity that is beyond our understanding in your life so governed by emotion, so full of tears, Come, am I forgiven? Must I kneel before a hand ready to strike, before a look ready to confront? Here I am. Are you satisfied?

There are therefore cavaliers only among men, but, varied as the family of beetles, this class of individuals is constantly in motion. It is found everywhere, in the high salons, in the abodes of the unfortunate, in the painter’s studio, in the office of the man of letters. You see some in plumed hats (please note that it is not only women who wear feathers in their hats), you find some with swords at their sides, with folders under their arms, clad in worn frock coats or a fashionable cloaks, workmen’s jackets, messenger’s hoods, holding a rag-picker’s hook. The cavalier is not only an elegant player around a roulette table, or a fine speaker in a theatre foyer, or an intrepid and graceful rider on an English chestnut or a dark Andalusian bay. He is there, still strong and quarrelsome, on the Quai de la Grève, or importunate and talkative when selling you a theatre ticket, or a drunkard and lout if his day of begging has been well spent. …. cavaliers are no more common in Le Grand Véfour and the Café de Paris than in the wine merchant of the Rue Quincampoix (for there must be at least one in that fetid street) or the smokiest taverns of the City. To live at the expense of fools is the first motto of those who have no other trade. The trained fraudsters, far from blushing at being so, regale each other each evening with their fine deeds of the day and, as skilled practitioners in evading the law, vary infinitely their manoeuvres, like those clever performance directors who, to attract the curious, give them a jumble of jokes and speeches, drama and farce. Among them, nevertheless, drama plays the largest role and the arm of justice, long uncertain, weighs finally on the wretches who have defied it. Faithful, however, to their code, they prepare, under the very bolts of the dungeons, the resources with the help of which they will later escape the knotted whip of the galley master of Toulon or Rochefort. Between the cavalier and the thief there is only the difference between the cells of Bicêtre and the jail of Brest. From one to the other is no more than a step, a minute, a look, a wish.

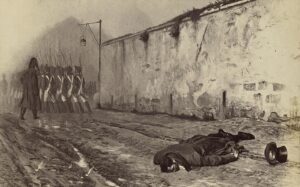

I was returning, one night, very late, to the Observatory. Almost opposite the low and polished wall, where Marshal Ney saw a moment of error and twenty-five years of glory extinguished, a rather well-dressed man came out from behind a tree and said, in an uncertain voice:

The Execution of Marshal Ney by Jean-Léon Gérôme. Ney was executed for treason, having supported Naploleon on his return from Elba and having commanded the cavalry at the battle of Waterloo. Hi reckless deployment of his troops in pointless cavalry charges was a significant factor in the French defeat. He commanded his own firing squad.

“Sir! Alms, please?’:

I quickened my pace.

“Sir,” he said to me, in a louder voice, “I don’t know where to sleep; give me something.”

– “I have nothing.” I said, and I was walking fast! ….

The man rushed forward, seized me by the collar, and in that loud voice demanded: –

“Sir! give me alms.”

“It is very late to be asking!”

“Yes; but it is also very late to refuse me.”

I gave him a silver coin, and he rushed away, without thanking me, toward the Boulevard Mont-Parnasse.

In the flickering light of the streetlamp, I had been able to distinguish the features of this man. They were downcast but not defeated; his threatening glare seemed to me artificial. One would have said that he was merely trying to appear frightening, like someone who raises his voice to a mutinous child who is being disciplined by fear. His speech was brief, rapid, schoolgirl-like; it reached me without emotion. I almost wanted, after those first moments of surprise, to invite this beggar to accompany me, arm in arm, to the Observatory. He did not give me time, and although I had at first given him alms without sympathising with him, I felt regret when I saw him run away so quickly.

In the morning, I told my brothers of my adventure with this assassin. They advised me to be more careful, and to take another route in future. The next day, I returned at midnight, alone, on foot, passing through the same dark alleys of that magnificent avenue that so majestically links the Observatory to the Luxembourg and which was created by that miserable Napoleon Bonaparte to whom we owe almost everything that is beautiful in Paris. I was not accosted by anyone that night, nor on the nights that followed, but two months later, I found myself one evening walking in the shadows alongside the moats that surrounds the Bastille (another large memento of Bonaparte!)

“Sir! give me alms! …

Immediately I recognized the voice from the Observatory, and I stopped short in front of this footpad and laughed. He was already trembling.

“I see. I now recognize you; you accosted me two months ago, at midnight, in an alley, near the boulevard Mont-Parnasse. I arrest you in my turn.”

“What will you do with me”

“What is done with thieves and murderers, and yet I am sure that you are neither the one nor the other. Follow me.”

I had spoken out loud. And the brigand followed me without saying a word, without daring to look at me. He could have escaped, for I was in front of him, two steps away. I turned around.

“I’ll wager you have neither swordstick nor pistol nor dagger about you.”

“I have not even a penknife; what would I do with it? You have said it: I am neither a thief nor a murderer; I have lived for more than six months from this kind of business, always waiting for someone to take me before the authorities, who will then provide me with food and my lodging. I thank you,” he continued in emotional tones, “I thank you for sparing me any more of these painful adventures.”

What could I do? Preach morality? Oh! good God! this man would not have understood me.

“If I give you these two hundred-sou pieces, what will you use them for? To survive? To get drunk?

“I have only been drunk twice, sir. The first, the day I began this kind of profession; the second, an evening when I stole a loaf of bread for my son.”

“What is your son doing now”?

“He awaiting for me, crying with misery.

“Where?”

“At his home, and mine.”

“Your home?”

“Is everywhere, and nowhere. I eat in the street, I sleep in the street, next to my child whom I warm. Yesterday, I wanted to drown myself; and, in desperation, I held out my hand to a passer-by. ‘Work,’ he said to me roughly. ‘I am asking you for work,’ I answered him. ‘Come’. I followed this rich man; he told me to take an enormous basket of fine wines to his home in the rue Saint-Georges. I walked a league, without shoes, following his cabriolet, and I arrived out of breath. ‘Here,’ he said to me, ‘here is your pay.’ I received twelve sous. This rich man robbed me of twelve sous, at least. But my son ate, I ate, we had shelter for a night, and I left my resolution to drown myself for the next day. That next day is today.”

This singular beggar was about to leave me but I stopped him.

“Here, here are ten francs.”

“ Ah! sir, with that and some twelve sous from people as rich as the one from the rue Saint-Georges, I will live for a month, and my son will eat bread.”

He had indeed shelter for a few days, that beggar-assassin-cavalier. Perhaps he also held his child’s little frozen red hands to warm by a blazing hearth; and I, after wishing him a better future, returned home joyful, and slept a sweet and calm sleep.

Who among you will be the first to throw a stone at my protégé?

Observer, will you follow me into this vast church where kneel so many devout people? See; there is one, close to the pulpit. What piety! What fervent raising of eyes to heaven! He at least knows how to pray, that one; it matters little to him whether anyone looks at him, listens to him, or scrutinises him! He sees only the altar where the sacrifice is consummated, he hears only the footsteps of the sidesman who beseeches alms for the souls in purgatory, for the poor of the parish, or for the costs of worship. Our devout person jingles a few coins in his pocket and presents an empty hand to the basin or embroidered purse of the supplicant. He does not want his offering to make a noise, he places it gently, solemnly and silently, and then goes to another chapel to attend a new mass, a new collection. Imitate his virtues, and live this life of ecstasy and alms.

Poor idiots! Do you need me to tell you that this is a cavalier, with combed hair, a brown frock coat, striped stockings, and copper buckles on his covered shoes? Well! that is so; and this man whose religious zeal you admire will not go to eat until he has heard at least five or six masses. His charity brings him money. As soon as the purse is presented to him, he ostentatiously places a small coin in it, and takes out a larger one, sometimes a more shining one. His fingers have eyes; he sees, by touch the one he should choose. In a second he has won a portion of his lunch; by noon he is sure to dine at little cost, and the hypocrite answers with a glance of benevolence the “God reward you” of the sacristan who hastens to pass near him . Each church, in its turn, sees this pious character,

Do you prefer the cavalier to the assassin?