In October 1827, a brief note appeared in the Bulletin de la Société de géographie, informing its readers of the contents of a letter dated 17 January 1827 that had been sent to one of the members of the Society’s Commission Centrale from a vessel moored in the ‘Calcutta River’ (the Hooghly). In translation it reads:

Monsignor

At this very moment and after the forty years of fruitless search with which are linked the names of d’Entrecasteaux, Bougainville, de Freycinet, Duperrey, etc., the expedition of the King’s Corvette Astrolabe commanded by M. Dumont d’Urville continues the work undertaken by those distinguished men and gives the world new proof of the interest inspired by the memory of the Comte de LaPérouse. You will therefore undoubtedly greet with interest the news I am sending to the Ministry of the Navy, of an expedition to investigate the place where this famous and unhappy navigator was shipwrecked.

[p.208] Based on information recently acquired by Captain P. Dillon about this disaster, the Company has just given him command of its ship Recherche in order for him determine for himself the truth of the reports he has received. Everything suggests that this voyage will be crowned with success, for, in addition to the fact that the place of the shipwreck has been positively identified, it is also said that several of the crew have survived exile and hardship since the loss of the Boussole and the Astrolabe. The Company’s ship, the Recherche, on board which I have embarked to collect the proofs that France has so long desired, will depart in a few days; it will first sail to Van Diemen’s Land, and from there it will head for New Zealand, where a local chief will be taken on board, and finally for the Mallicolo Islands, where we hope to find the unfortunate Frenchmen who must have lived on those islands after the shipwreck of LaPérouse. I hope to be able to provide in person a report on the outcome of this voyage, which all of France, and the navy in particular, will be awaiting, and for the success of which we cannot hope too highly.

The vessel from which the letter was written was the survey ship belonging to the Honourable East India Company, the HEIC, and, being English and not French, was named Research, and not Recherche. However, the 26-year-old author of the letter, Eugène Chaigneau, was indeed French. How did he come to be on board?

It is a complicated story that begins in the last days of the Ancien Régime in France but, perhaps not coincidentally, the letter that immediately preceded Chaigneau’s in the Bulletin was from Joseph-Paul Gaimard, formerly assistant surgeon on the corvette Uranie and at the time of writing surgeon/naturalist on the corvette Astrolabe, so a relevant extract from his Uranie diary is a good place to begin. Into that diary, and before beginning his account of the actual voyage, Gaimard transcribed a number of letters of advice sent by various Paris savants and politicians to the commander and officers of the Uranie before her departure in 1817, and one of these was from the state’s leading pharmacist, Cadet Chevalier de Gassicourt. At one point he interrupted his list of suggestions by reminiscing on events that had taken place more than 30 years before, when he was only seventeen.

I was in Versailles in 1786 when M. le Bailli de Suffren presented the son of the King of Cochinchina to the court. He was seeking help from France to restore his father to the throne of his ancestors, and I had the honour of accompanying him to the porcelain factory in Sèvres. The Bishop of Adran, who acted as his interpreter, showed us, as very rare precious objects, the bracelets, garters, ring and cap worn by the young Indian prince. These were all made of an elastic coral-red gum, and in their thinner parts were as translucent as wax. It follows that there is in Cochinchina a beautiful red elastic resin (natural or artificial) that is not affected by exposure to air. (Gaimard, p.92)

Cochin China was the name by which the southern Vietnamese kingdom that eventually expanded into an empire taking in the whole of Vietnam was known in Europe, and the meeting was one step in the campaign by a missionary priest, Pierre Joseph Georges Pigneau, the nominal Bishop of Adran, to persuade France to intervene in the civil war raging in that country. The cash-strapped French government was reluctant, but in 1787 a formal treaty (confusingly know as Treaty of Versailles) was signed, in which France agreed to supply troops, armaments and warships to support the restoration of the Nguyen dynasty, receiving in exchange Con Son island and concessions in Da Nang, then known as Touraine. However, the Comte de Conway, an Irish adventurer who had become governor of French India, was obstructive[1], and the monarchy was overthrown in France before any aid was actually sent. Neither the revolutionary government that took its place nor the Napoleonic Empire that succeeded it was interested in, or capable of, overseas adventures.

That did not deter Pigneau. He gathered together a group of French mercenaries and placed them at the service of the Nguyen family. Among them was Eugène’s uncle, Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau, and thanks in part to his military expertise and that of his colleagues, the Nguyens triumphed and the father of the young prince mentioned by Gassicourt ascended the throne as the Emperor Gia Long.

Pigneau died in 1799, but members of his team continued to be a presence in the nascent empire, and Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau was the most influential of these. He married a Vietnamese, took the name Nguyen Van Thang and was awarded the rank first of a mandarin and then Grand Mandarin. In that capacity he advised the emperor in dealing with Europeans but he made little headway in promoting PIgneau’s project of converting the country to Catholicism. The Nguyens remained solidly Confucian, and suspicious of foreigners, and when Achille de Kergariou was despatched from France by the restored monarch to negotiate a new treaty, he met with a frosty reception and returned home empty-handed after spending less than three weeks in the country.[2] Jean-Baptiste, who was still in Vietnam at this time, might have been helpful but was reportedly recovering from wounds and unable to leave Hué, so Kergariou never met him.

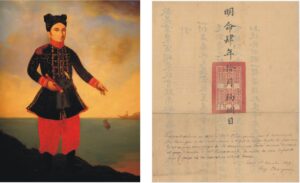

Figure 1 (left) Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau, during his time as a mandarin at the court of Gia Long.1805 Vietnamese painting.reproduced in Mantienne “Monseigneur Pigneau de Behaine” (Right) Passport issued to Eugène Chaigneau in 1824., annotated by him.

In the year after Kergariou’s visit, Jean-Baptiste made a brief visit to France, returning with the title of French consul, which, according to Kergariou, he already had. With him he brought his 21-year old nephew, Eugène, to work with him as a consular agent on a salary of 1,500 francs, but the political situation in Vietnam had changed dramatically while he was away. Gia Long had died and had been succeeded by his fourth son, the avowedly anti-European Minh Mang. In June, 1822, Labartette, Bishop of Veren and head of the Catholic mission in Cochin China, wrote a letter to the Missions headquarters in Macao in which he said that::

….. this King detests all dealings with the Europeans. He is at present showing a friendly face to our two gentlemen Chaigneau and Vannier who are here; but I am certain he would like to see them removed far away from him. He is destroying all that his father has done, and he is superstitious to the last degree. Since he is very well educated, he is the greatest partisan of Confucius and of all the literati. He threatens to chase us all out of his kingdom on the least complaint which might be made to him against us. Since he has ascended the throne our holy religion has made very little progress. (Lamb, p.171)

Finding his influence greatly diminished, Jean-Baptiste left the country in 1824, bequeathing his nephew a poisoned chalice by arranging for him to succeed as consul, with a salary of 7,500 francs.

The consular post was the first in a series of disappointments that would define Eugène’s rather short life.[3] The Emperor refused to recognize him as a representative of France and, with no meaningful role to play, he left the country on the Larose, the trading vessel of the Balguerie Sarget company that almost alone maintained trading links between the empire and Europe. For once in his life, his timing was good, because he reached Calcutta just as the Research was being prepared for sea, and Dillon, seeing the value of having a Frenchman of good reputation on board to vouch for his having handled any finds respectfully and catalogued them completely, invited him to join the expedition. The offer was accepted with alacrity, and, once on Vanikoro, Eugène played a full, if not outstanding part, in the investigations into the fate of the ships of LaPérouse. He also, after the return of the Research to Calcutta, accompanied Dillon to London, and then to Paris, but there, sadly, the two fell out. According to Louis Finot, Dillon ‘fully intended to keep the honour of the expedition for himself and forbade him from publishing anything about the voyage’, but this cannot be accepted at face value. Dillon did not have the power to do what is suggested (at the most, he could have denied Eugène access to his own papers), and if he did indeed wish to keep ‘the honour of the expedition for himself’, that is entirely understandable, because that is where it rightly belonged.

Eugène, meanwhile, was suffering yet more disappointments, because it proved impossible for him to immediately continue a diplomatic career.[4] The consular agency in Cochinchina was abolished and the Department of Foreign Affairs initially declined to offer any other position to someone they clearly saw as a failure. The navy, only marginally more sympathetic, granted him a lump sum of just six hundred francs in recognition of his “noble devotion”! In 1829, however, the Department received some suggestions of a softening in Ming Mang’s attitude that led them to suppose he might be more willing to accept French consuls, and Eugène was appointed Vice-Consul in Touraine. He left France, full of hope, on 15 December1829, on the sailing ship Saint-Michel, but this was wrecked in a typhoon on the Paracels. Eugène barely survived, and when he finally reached his destination, having little more than the clothes he stood up in and without any of the gifts expected of foreign representatives, he was simply ignored. The following year, he was found in a state of complete destitution and ‘abandoned to the insolence of the country’s authorities’ by the commander of a visiting French vessel, the Favorite, who took him on board because, as he wrote to the Minister, it is not appropriate for him to remain here’ (Finot, p.426). Eugène’s bad luck followed him to Calcutta, where he fell ill and had to remain until he recovered, and he only reached France in June 1832.

After his return to France, The Ministry delayed the payment of Eugène’s salary for as long as they could and denied him any compensation for the losses he sustained in the shipwreck, but he was eventually re-employed in 1835 in the Philippines as a second class honorary consul in Cavite and consular agent in the chancellery in Manila.[5] From there he was promoted in 1840 to the rank of Consul-General in Singapore, and it briefly seemed that his career was at last progressing, if only modestly, but from 1842 onwards his health deteriorated and increasingly serious attacks of malaria, which he might first have acquired on notoriously unhealthy Vanikoro, forced him to ask to be replaced. Worn out and ill, he returned to France and died in Lorient a few months later.

[1] According to Barrow, A voyage to Cochin China, Pigneau had affronted Conway’s mistress, who was also the wife of his aide-de-camp and a noted beauty, by refusing to visit her in view of her scandalous behaviour. Enraged by his comments, she manipulated her lover into declining to assist in implementing the treaty.

[2] It may have been in part his feelings of failure that caused Kergariou to disregard his duties as frigate captain to the extent that he allowed his ship, the Cybèle, to collide with the Uranie off Saint Paul on Réunion in August 1818.

[3] According to his gravestone in the cemetery at Lorient, Eugène was born on 19 September 1799 and died on 27 May 1846, so he lived for little more than 46 years..

[4] Eugène’s achievements during that life have not (yet?) been recognised by a Wikipedia page and, with the exception of his participation in the Vanikoro expedition, most of what is available on the internet concerning his life comes from the biography by A. Salles (J.-B. Chaigneau et sa famille, Bulletin des Amis du vieux Hué, 1923) of his much more famous uncle. This is itself hard to access, but much of what in it concerns Eugène was summarised by Finot in his review of the book.

[5] The senior French representative in the Philippines was Théodore-Adolphe Barrot, whose English wife was the daughter of the British Rear Admiral Thomas Manby, the man who first brought to Europe the rumours of salvage from LaPérouse’s ships being traded among the islands of the south-east Solomons.