On 9 October, GNS Science, which is New Zealand’s Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited and effectively its geological survey organization, made a startling announcement. “Zealandia”, so its publicity department contended “just became the first continent to be completely mapped”. A part of the strap-line went even further. This was, it was claimed, “A world first in undersea mapping”.

But what is Zealandia, and are these somewhat extravagant claims justified?

Anticipating, perhaps, at least the first part of this question, the publicity department provided some additional detail. It told its readers that:

“In 2017, a groundbreaking study led by GNS Scientists outlined evidence of Te Riu-a-Māui / Zealandia’s continental characteristics – from its thick and geologically varied crust, to its size and isolation from Australia.”

It was a claim that took me back to the (geologically) heady days of the early 1970s and specifically to the Twelfth Pacific Science Congress, which was held in in Canberra in August and September 1971. Pacific Science obviously covers a very wide field, but at this particular congress it was the geologists who hogged the limelight. The 1960s had seen the advent of Plate Tectonics, but the previous Congress, in 1966, had been a little too early for its impact to be felt. By 1971 the Young Turks of Pacific geology were in full cry, and at their head were the New Zealanders, delighted to be, for once, centre stage. It had arguably been in New Zealand that the flame of continental drift had been kept burning most strongly during the long years of the first half of the Twentieth Century, when Wegener’s idea that continents could move were being comprehensively trashed by the world’s physicists. How, the New Zealanders, and their colleagues in Australia, South America and South Africa, could southern hemisphere faunal distributions be explained if its widely separated land masses had not once been in contact? Now, at last, they were being proved right.

And, in 1967, there had been Nova.

Anyone who wants to get a feel for those days, when the science of geology was being revolutionised, could do no better than read Bill Menard’s book Anatomy of an Expedition, a description of the two-ship Nova expedition. For those who can’t get their hands on the book itself, extracts can be found online, dealing mainly with the planning stages, and including the reasons behind the name given to the expedition. It was, it was quickly realised, going to be targeted at the seas surrounding the islands of the New Hebrides, New Guinea and New Caledonia – and, of course, New Zealand. By the time it was over, the essential framework of those seas and islands had been established, but there was much left for later expeditions to do, by way of filling in the details. Now, in October 2023, and if the publicity department of GNS Science is to be believed, that work is complete. Zealandia, the mainly submerged continent that the ships of Nova crossed and recrossed, has been ‘completely mapped’.

But is it true? Anyone turning to the paper on which, it seems, that claim is based, is in for a surprise. Its title alone is sufficient to reveal the real picture. What is presented, we are told, is just a ‘Reconnaissance Basement Geology and Tectonics of North Zealandia’, and, because it was published in the AGU’s open-access journal Tectonics, it is there for all of us to read. What those who take that step discover is that, far from being anything to do with mapping in a wider sense, the discussion is based almost entirely on the results of dredging programmes. According to a statement made in the text “IN2016T01 DR3 and DR4 [i.e. Dredge Sites 3 and 4 on cruise IN2016T01] are the main topic of this paper. Like DR5, these were made in a submarine canyon incised into the northeast side of Lansdowne Bank”.

Lansdowne Bank, the accompanying maps show, is the main shallow-water culmination on the Fairway Ridge, a subsea feature at the extreme northern end of the Lord Howe Rise. This is an area of some importance for an understanding of the rise as a whole, but a smallish number of dredge hauls, even when examined in the detail provided by Nick Mortimer and his colleagues, can surely offer only a very slight basis for the very large claims made in the press release. There is, of course, more, than that in the paper, but not a great deal more. Other dredge sites are discussed, or at least mentioned and placed on a map, and there is an appraisal of the regional magnetics, based on the regional EMAG2 compilation, which is distributed on a 2-arc-minute grid, equivalent to a little over 4 kilometres in the worst case, close to the equator

And gravity? Well, it does get a mention. Two mentions, in fact.

The first is that :

“Using onland geology maps and offshore sub-circular bathymetric, gravity and magnetic anomalies, Mortimer and Scott (2020) identified more than 500 volcanoes across North and South Zealandia that were not obviously rift-related”.

In all probability, much of the bathymetry used in this study was derived from free-air gravity values that were, in their turn, derived from satellite altimetry of the sea surface, so there is an element of circularity in quoting both bathymetry and gravity as sources. The method is undoubtedly valid, despite this, but isolated volcanoes are anomalous almost by definition, and their presence or absence tells us little about the nature of Zealandia as a whole.

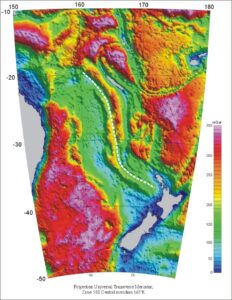

Bouguer gravity of North Zealandia. Crustal thickness is inversely correlated with Bouguer gravity, and in this presentation continental crust of normal thickness appears blue, stretched continental crust is green and oceanic crust is red and purple. The dashed white line tracks the apparent persistence of the thickened crust of the Fairway Ridge from its type area at the northern end of the Lord Howe Rise to the margin of New Zealand’s North Island.

The other mention of gravity was more directly relevant to Zealandia.. It read:

“Using seismic, magnetic and gravity data, the Fairway Ridge can be traced hundreds of km SSE beyond its bathymetric expression and is colinear with the West Norfolk Ridge.”

That sounds worth following up, but there is a lacuna in the North Zealandia paper. No gravity map is presented. That is, however, an omission not difficult to remedy, again using the satellite derived data. It seems worth doing, but which gravity – free-air or Bouguer?

It is at this point that we are reminded yet again of the publicity department’s claims. Is the Zealandia idea really a new one, or is the idea of much of the Tasman Sea being occupied by somewhat stretched continental crust not a very old one, going back to the Nova expedition or even earlier? Bathymetry alone suggests that, and has been sufficiently available for quite a long time. Now, with the satellite gravity data available, and fully recognising the danger of circularity mentioned above, a Bouguer gravity map can be obtained by combining bathymetric and free-air grids. It dramatically identifies the regions underlain by continental and oceanic crust, because continental crust is much thicker.

The map offers food for thought. The Fairway Ridge, it seems, extends all the way to New Zealand.

A closer look is obviouly desirable. But that is a matter for another blog.