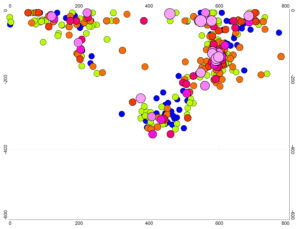

Some twenty years ago I wrote a paper about subduction in the Banda Sea region. At the time the majority consensus was that there were two separate subduction zones, one north facing, the other south facing. By plotting earthquake hypocentres on north-south swathes across the Banda Sea, as in Figure 1, I was able to show that in reality these zones involved the same slab of subducted lithosphere. Only in that way could one explain the demonstrable fact that the hypocentres in every swathe bottomed out at the same depth, a depth that decreased steadily from west to east. It is a feature of these plots that the southern arm of the U always involves more earthquakes, and on average, more intense earthquakes, than does the northern arms.

Figure 1. The scoop-shaped Banda subduction zone. Earthquakes from the catalogues of the National Earthquake Information Centre for the period 2000 to 2020, in the N-S swathe between 128.5oE and 129oE. Circle sizes and colours are dependent on earthquake magnitude (Mw). No vertical exaggeration, distances in kilometres.

Shortly after the paper was published I went to a conference in the Transylvania region of Romania, in which there was much discussion of the very odd pattern of deep earthquakes associated with the Carpathian Arc, an orocline (highly arcuate mountain belt) with dimensions comparable to, although somewhat smaller than, the Banda Arc. The Carpathian deep earthquakes are confined to a roughly cylindrical zone in the south-eastern bend of the arc, near the town of Vrancea. A degree of similarity with the situation in the Banda region was evident in the plots that were shown. Although earthquakes are in general much more widespread in Banda, they are very definitely most frequent and most intense near the south-eastern bend in the arc, and I wrote a second paper pointing this out This was published in 2005, by which time I had retired from teaching, and my geological/geophysical focus had moved up to the Philippines. In London work continued on the Banda area within the successor to the university’s Southeast Asia Research Group, and extreme extension had been mapped on islands in the northern arm of the arc.

What goes around comes around, as they say, and in 2022 I was invited to an Alpine conference in Ljubljana to talk, within the context of IGCP 710, about some of the work I and Jenny Barretto had been doing in the Philippines, .The discussion broadened, and prompted me to think again about what was going on in the Banda Arc and under the Banda Sea. One thing that is clear from Figure 1 is that the subducted slab, measured around its semi-circumference, is a great deal more extensive than the distance between the points where it reaches the surface, measured across the Banda Sea. The necessary extension becomes even greater when the east-west dimension is considered. It was in fact the extreme mechanical improbability of this arrangement that led to the ‘scoop’ solution being rejected for so long. The original subducted slab must be either drastically stretched, or it must have ruptured, probably in a number of places. Given that the ability to sustain earthquakes implies rigidity, stretching without rupture seems likely to be strictly limited; it is probable that the slab is fractured in many places. The plots of earthquakes in successive N-S swathes shown in Figure 2 strongly suggest that this is exactly what is happening.

Figure 2. Successive half-degree swathes of Banda Arc seismicity, focussing on the southern arm of the orocline. Earthquakes with magnitudes (Mw) greater than 5, from NEIC catalogue for 2000 to 2020. No vertical exaggeration, distances in kilometres.

The plots in Figure 2 not only suggest a subducted slab in an advance state of disintegration, but that at least one fragment is sinking vertically. The Carpathian orocline is considerably older than the Band Arc and the collision with the continental foreland is virtually complete. Perhaps what we are seeing at Vrancea is one last fragment, the last of several, following its predecessors into the mantle.