In 1823 Basil Hall, a British naval officer who was the first person to measure gravity in the Galapagos Islands, advised anyone who might follow him in taking gravity pendulums overseas to recognise the

… advantage which … would arise from having the whole experiment performed in England, by the person who is afterwards to repeat it abroad, not under the hospitable roof of Mr. BROWNE … but in the fields, and with no advantages save those he could carry with him.

This was sound advice, because the helpfulness of Henry Browne was legendary. It was in the private observatory he established in his town house at 2 Portland Place that the first accurate measurements of gravity in the United Kingdom were made (by Henry Kater), and there are several papers in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society that testify to similar assistance being given to others. It is a pattern that is consistent with the rather fragmentary records of his career with the East India Company in Canton. In 1792 the directors of the Company recommended him to the (ultimately unsuccessful) Macartney mission to the court of the Chinese emperor as “a man of much tact and great experience in China”.

There is, however, one dissenting voice in the general chorus of approval. On December 30, 1796, while anchored at Macao, where he was waiting to escort the Company’s fleet on the first part of its homeward voyage, Rear Admiral Peter Rainier wrote a letter to the Company that had a very different tone. While expressing his thanks for recent services to Richard Hall, then President of the committees that ran the Company’s affairs in China, Rainier was scathing in his references to events earlier in the year.

Am sorry ’tis not in my power to express an equal satisfaction with regard to your exertions in complying with my request to assist Lieut. Dobbie, on his arrival at your Factory, as they do not appear to me to have been made with that earnestness, the Public Service required, and which from your very respectable situation in the Hon’ble Company’s Service, I had flattered myself they would have been ; nor with the inattention shewn to my recommendation of having the homeward bound Ships to call at Amboyna, which would have enabled me to have acquired the possession of Ternate & its dependencies for the King, as suggested in my letter, the loss of which opportunity may be much regretted by his Majesty’s Ministers.

According to Hosea Amos, who quoted this extract on p291 of Volume II of his “Chronicles of the East India Company trading to China, 1635-1834”, the person whose ‘exertions’ had been found wanting was Henry Browne. Since the portrait painted is very different from that drawn by everybody else, of a person not only almost obsessively helpful and co-operative but also efficient, there must, one feels, be more to the story. There is, but much is still obscure and uncertain, and the background is complex.

The China Trade

Although in most people’s minds the East India Company is remembered principally for its rule in India, in the late 18th Century its finances revolved around the China trade. Every year between the end of June and the middle of September the Company’s ships would dock in Canton, carried there by the favourable winds carrying them north through the South China Sea. The Company’s agents, freed from their ten-month confinement to Macao, would be there to meet them. From 1769, when he began his employment as a lowly ‘writer’ on a salary of £100 per year, until 1796, when he retired from his post as President of the Select Committee, Henry Browne would be there to meet them. This was the start of the trading ‘season’, always known by the year in which it began. It would end in the first few months of the following year when, laden with tea and silks and with winds now to the journey south, the ships would leave.

Admiral Rainier

In 1795 Rainier had command of all the Royal Navy’s ships in the Indian Ocean and the Far East, and he was not going to let pass the opportunity presented by the ejection of the Dutch Stadtholder and the creation of the Batavian Republic with French backing. The Netherlands became officially an enemy and he set about sweeping up their possessions. On 16 February 1796 he captured Ambon, their main base in the Moluccas, without a fight, and on 9 March, in the face of slightly more resistance, he occupied Banda, the original ‘Spice Island’. During the action one officer, a Lieutenant Dobbie, distinguished himself and was selected to carry the despatches on the first stage of their journey back to England. For this task he was given command of the Dutch brig Harlingen, for the capture of which he had been largely responsible and which had been renamed the Amboyna and bought into the Royal Navy. He was just about to leave when news arrived of an Ambonese revolt against any sort of colonial rule, whether Dutch or British, and Rainier decided there were more urgent things to do than send letters to London. He had the Amboyna loaded with a valuable cargo of spices and despatched it to Macao with a letter, dated 5 May 1796, to Henry Browne to arrange the provisioning of the fleet. It was Browne’s perceived failure to respond adequately that lay behind Rainier’s letter of December 1796.

That, at least, is the story told by the secondary sources, but there are reasons for thinking it is less than, or more than, the truth.

Dobbie’s journey

First among the oddities is the timing of Dobbie’s journey to Macao. When news of the revolt in Ambon arrived, the Amboyna had been about to set out for India with the mails, a mission so inessential that, once the brig had gone, no immediate alternative arrangement was felt necessary. If obtaining supplies and diverting the East India Company’s fleet were really so crucial, then it seems very odd that the brig was not sent to Macao as soon as Banda had fallen. As it was, Dobbie carried with him a letter that was not written until almost two months after that event.

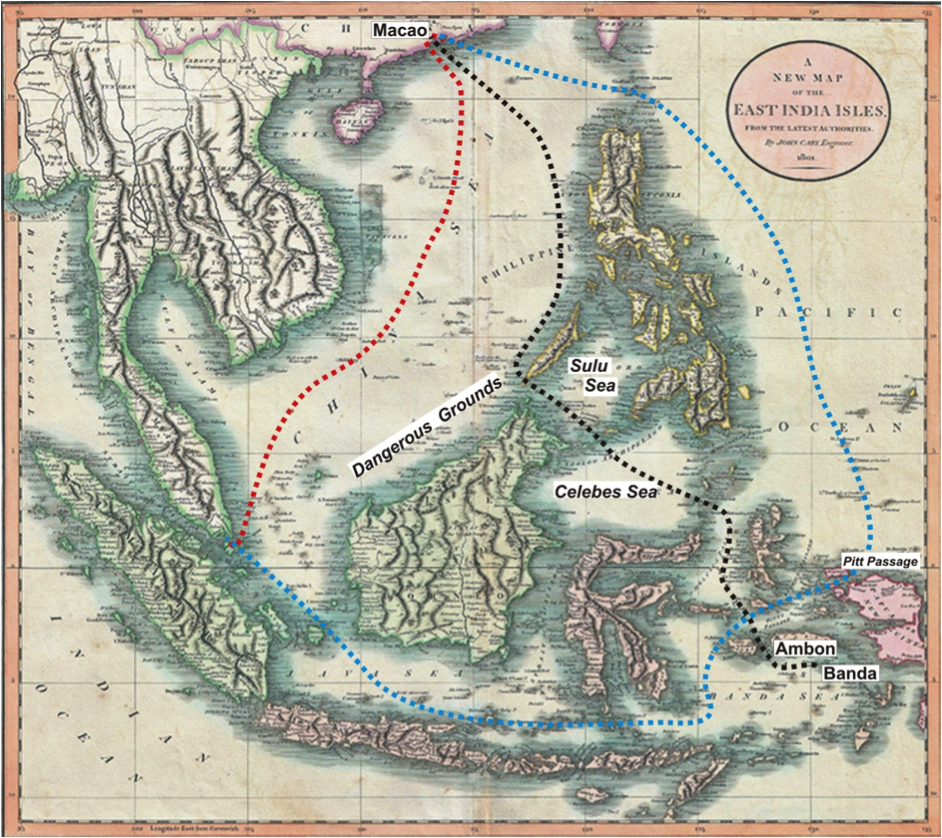

The trade routes of the Indies. The ‘normal’ route taken by the East India Company fleets leaving Macao is shown in red and the alternative, used out of season and when it was necessary to avoid hostile warships operating in the South China Sea, in blue. A possible version of Lieutenant Dobbie’s route from Banda to Macao via the Celebes and Sula Seas is shown in black.

The delay seems even odder when its likely consequences are considered. To be effective, Dobbie had to arrive in Macao before the East India Company’s ships left, which was usually before the end of February when the favourable winds ceased to blow. In a normal year the season’s sailing would have left Macau by the time Banda fell. Dobbie must have known about this because he had been employed by the East India Company during the peace that preceded the revolutionary wars and would have told Rainier if he did not already know. It is true that sailings later in the year became more common after 1760, using the route pioneered by the East Indiaman Pitt that began with a passage between Taiwan and Luzon and re-entered south-east Asian waters via straits north of the western New Guinea, but it would have been very optimistic for Rainier to have relied on this, because he could not have known for certain.

None of the sources record the time it took Dobbie to reach Macao, but it was not an easy voyage. He was not in good health and his friend and fellow officer, Arthur Farquhar, came on board as a supernumerary to provide back-up. The distance was more than four thousand kilometres and at that time of year the prevailing winds were light and from the north, so a fast passage was not to be expected. The route chosen took the brig past Ambon into the Molucca Sea and then cut through the chain of the Sangihe Islands into the Celebes Sea. Dobbie would have had to take one of the straits through the Sulu Islands into the Sulu Sea and eventually reach the South China Sea by passing either north or south of Palawan. Once past Palawan it would have been plain sailing to Macao at the mouth of the Pearl River delta, as long as the reefs of the aptly-named Dangerous Grounds were avoided, but somewhere in the ‘Sooloo Seas’ the ship had run aground and when she finally reached her destination she had to be beached on Tuya Island, opposite Macao, for repairs. This task was left to Farquhar, while Dobbie went up-river to Whampoa, where the eleven ships of the season’s second tea fleet would have been about to depart, ‘three months later than the usual close of the season’. Browne would have been with them, and not in Macau as might have been expected at that time of year, since the Company records show that he left for England with the fleet on June 24 at what was intended to be the end of his service.

The letter

The letter of complaint also poses questions. Hosea Morse provided only the extract quoted above. Other secondary sources are even less informative and it was Morse who stated that the letter was addressed to Henry Browne. This makes little sense. Browne had left China six months before the letter was written, and Rainier would (or should) have been well aware of it, since he was writing from Macao. However valid his grievance, would he really have bothered to commit it to paper when its subject was long gone?

If Rainier knew that there would be a late sailing in 1796 (confusingly, part of the 1795 ‘season‘, which began in June 1795), he would have expected the fleet to use the eastern route. He could have easily had them intercepted in the narrow Pitt Passage between New Guinea and Batanta and could then have obtained some of the help that he needed. The mere sight of a combined fleet of more than twenty ships off Ternate would probably have been enough to persuade the Dutch garrison to surrender, since a much smaller fleet had achieved the same result against the better protected settlement on Ambon. But Ternate remained unmolested – was he simply trying to cover himself against possible criticism for not having captured it when he had the chance?

It was all, in any case, irrelevant, because Banda and Ambon were returned to the Netherlands under the terms of the Treaty of Amiens a few years later, and Ternate would have been returned as well.

Aftermath

Rainier considered that Dobbie acquitted himself ‘so much to his satisfaction’ that he subsequently recorded the fact in public orders, but it is hard to understand why. While he could certainly not have been blamed for the failure of Rainier’s plan, it is difficult to find anything exceptional in the very limited number of things that he was able to do. The best that could be said of him is that, when given an impossible task, he tried very hard to carry it out.

None of the three principal actors in this minor drama seem to have suffered either reputational or financial losses as a result. Rainier retired from active service in 1805 with a vast fortune, amounting to some £250,000 derived from his ‘Admiral’s share’ of the prize money for the ships captured under his command. He did not, however, live long to enjoy it, dying in 1807. He left 10% of his estate to the nation, to be put towards the reduction of the national debt. His failure to take Ternate appears to have been hardly noticed. The island would surely in any case have been handed back to the Dutch along with Banda and Ambon under the terms of the Treaty if Amiens.

Dobbie’s career continued to advance as long as Rainier was in command. He reached the rank of captain and distinguishing himself in a number of actions, but his relations with Rainier’s successor were less happy and he eventually returned to home waters. He never reached Flag Rank and failed to obtain a command in the much reduced navy that existed after the end of the Napoleonic wars. Instead he married, went into politics and became Deputy Lieutenant of Essex.

Henry Browne also came back to England with a considerable fortune. Although probably not on the scale of Rainier’s, it was sufficient for him to buy North Mymms Park and House from the Duke of Leeds, and 2 Portland Place where he established his observatory. He married the sister of Edward Sabine, who was to become President of the Royal Society, and the couple had six children. Browne was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1797 and, although he seems to have made no direct contribution to science, his indirect contributions, in terms of the facilities he made available to others, were enormous.

In 1810 he returned briefly to Canton to sort out the station’s affairs, which had suffered under his successors, but he remained there for only a single season before returning for reasons of health. He died in Portland Place in 1830, having moved permanently into town a few years earlier.