In 1970, in the early days of plate tectonics, I had a paper published in the Journal of Geophysical Research identifying the Woodlark Basin east of New Guinea as an actively extending young ocean. Since at the time my co-workers in Papua New Guinea regarded this as wild speculation, I thought I might as well end the paper with some further wild speculation, and I wrote

The association of central shoaling of a trench, enhanced volcanism in the island arc, and reduced deep-focus seismicity appears to be repeated in the New Hebrides (Benoit, 1967; Warden, 1967), but in this group the active volcanoes are separated from the deep ocean by large non-volcanic islands on a frontal rise. Further investigation of the recurrence of this pattern in Melanesia may prove fruitful.

This comment focused on the trench. The Woodlark Basin spreading ridge is subducting at the Solomons Trench, reducing its depth to such an extent that it is now often described in terms of separate and distinct North and South Solomon trenches. The shoaling of the Vanuatu (at the time, New Hebrides) Trench is associated with a topographic feature on the downgoing plate known as the D’Entrecasteaux Ridge, which resembles the Woodlark spreading centre in impacting the trench at a high angle, but it is certainly not a spreading ridge. It was at the time poorly mapped and little understood, and even today its role has not been fully explained.

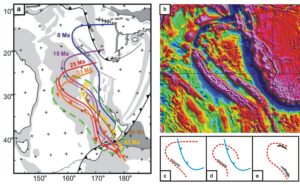

In 2007 Wouter Schellart, Brian Kennett, Wim Spakman and Maisha Amaruet published a paper that supported the now increasingly generally accepted interpretation of the New Caledonia ophiolite as the forearc to a west facing subduction zone associated with the Loyalty Islands volcanic arc. More controversial but increasingly gaining acceptance was their continuation of this arc south along the Three Kings Ridge and thence to New Zealand’s Northland province. This interpretation, and its evolution through time, was shown in their Figure 2; the core of the paper was mantle tomography and two slightly different variants were shown of the history of this arc, using different mantle reference frames. Their Figure 2a is reproduced below as Figure 1a.

Figure 1. (a) Figure 2a from Schellart et al. (b) Free-air gravity of the D’Entrecasteaux Ridge and adjacent areas, based on grids derived from satellite measurements of geoidal undulation expressed as variations in sea-surface elevation with respect to the Earth ellipsoid. (c) New Caledonia, the Vanuatu Arc and the northern Loyalty Arc, as extracted from Figure 1a. (d) The alternative oroclinal form of the subducted Loyalty Arc, as suggested by Figure 1b. (e) The Banda Arc, reversed and rotated, at the same scale.

In these diagrams the fate of the subduction zone south of New Zealand’s Northland was left undefined, but the northern limit was placed very firmly at the D’Entrecasteaux Ridge, which was interpreted as the trace of a rectilinear transcurrent fault active in the 33-43 Ma interval, most of which has now been subducted at the Vanuatu Trench (Figure 1a). However, free-air gravity values derived from sea-surface satellite altimetry suggest something very different. As shown in Figure 1b, there is no suggestion of any rectilinear continuation of the ridge east of the trench, which is not necessarily surprising, but there is a very strong suggestion of a curvilinear continuation to the south, which rather definitely is.

Free-air gravity at sea is dominated by the effects of bathymetry but, because sediments are generally less dense than basement rocks, there is enhancement of basement ridges. The curvilinear feature that continues east of the Vanuatu Trench that is so obvious in Figure 1b is certainly identifiable in the bathymetry, but is a much less prominent feature, and is easily overlooked. Gravity, however, demands that it should not be overlooked, and that an explanation be found. What can that be? To me, because of a background in the geology of eastern Indonesia, the similarity to the Banda Arc was irresistible, so much so that I investigated that possible analogy a little furthe, with the results shown in Figures 1c – e

Figure 1c is simply an extract from the map presented by Wouter Schellart and his colleagues, showing just New Caledonia , the Vanuatu Trench, the former Loyalty subduction zone and its strike-slip termination along the D’Entrecasteaux Ridge, and its hypothesised subducted extension. Figure 1d shows, to the same scale, the same features but with the rectilinear extension replaced by the curvilinear extension apparent on the free-air gravity map. Figure 1e shows, to the same scale, the Banda subduction zone, located geographically by the inclusion of the islands of Timor and Seram, the principle islands of the Banda orogen or orocline. The map has, however, been reversed and rotated to emphasise the fact that not only is the shape of the ‘curvilinear D’Entrecasteaux Ridge’ reminiscent of the shape of the Banda Arc, but that the geographic extents are similar same size. Nor is this all. The island of Timor, on which Australian continental basement is overthrust by thrust sheets originating on the Asian Plate, is similar in size to and shape to New Caledonia and is in a comparable position in relation to a curvilinear subduction feature.

Can this be just a coincidence? It seems to be asking a great deal a chance to suppose that it is. But if there really are similar processes at work in these two areas, a whole range of new questions are posed. They include those concerning the origin, and even the reality, of the scoop-shaped subducted lithosphere beneath the Banda Sea, and much hypothesised possible relationship between the Eastern Papua and New Caledonia ophiolites.