Coincidentally, two recent threads on LinkedIn brought Assynt to mind.

The first was a discussion about the reasons for the decline in the number of students studying geology in UK universities. Sadly, among the reasons cited was …. fieldwork. Which immediately made me think of Assynt, where so many of the UK’s geologists have been introduced to the joys and miseries of field geological mapping.

And whilst that was in my mind, another thread appeared, emanating from Birmingham University, celebrating International Women’s Day and singling out six women in particular for their contributions to geology. The sixth on the list (they were in chronological order, beginning with Mary Anning) was Janet Watson.

The idea that fieldwork would have been a reason for avoiding geology would have been anathema to Janet. The Women’s Day commemoration notes that she was ‘a staunch advocate of making primary observations through mapping in the field to build on her theories’, and the memorial to her on the website of the Geological Society of London, (she was the Society’s first woman president) reproduces some of her beautiful field sketches (including one of her younger self in the field in rain-soaked Scotland).

As a geophysicist I was never formally taught by her, but I did have the chance to get to know her a little when we were both doing fieldwork in her beloved Northwest Highlands. In Scourie she was well known as ‘tapping Jenny’, famous, in legend at least, for touring her field area on an old bicycle with a capacious basket to carry her hammer and, thanks to that hammer, her rock samples. The bycycle was not in evidence in the early 1970s, but it is almost impossible to think of Janet without thinking of that area, and that, of course, includes Assynt. If one was setting out to design a virtual reality field course to introduce first-year geologists to field mapping (sadly, it may come to that), one could scarcely do better than replicate Assynt.

Better by far to use the real thing.

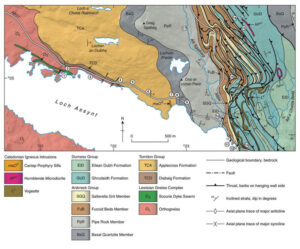

The Loch Assynt training ground. Map accompanying the excursion guide by Paul Smith and Robert Raine, British Geological Survey.

Why is Assynt special?

Locations 1 and 2 on the Smith & Raine map present for inspection outcrops of the three main classes of rocks; sedimentary, igneous and metamorphic. Admittedly, the exposures of the latter two are not brilliant, but there is enough there to introduce the concept to beginners in geology, and there are many alternative sites in the surrounding area where they can be seen more clearly. At Location 1+2, however, there is something more to see. An unconformity. On the uphill side of the road there is a very nice, clear and simple, unconformity, of sediment on metamorphic. A chance to explain the concept of unconformity, in the context of two very different types of rock.

It gets better. There is a second unconformity, angular and of sediment on sediment (Locations7+8 and the continuatiion in the hinterland), a chance to get students to imagine that boundary extending out of the ground surface and hanging in the air, and for them to predict where else they might see it. And for the brighter ones to wonder how it is that it is the older unconformity that appears to be almost horizontal, while the younger has significant dip. There is a stream section (the stream of Location 17) to be mapped, with dips and strikes to be measured – how many students will solemnly measure just one dip and strike on a well exposed part of a fold, and plot that on their field sheets, without considering that if they had made the measurement a couple of feet away, they would have got a completely different answer? There are different lithologies to cope with: how to tell carbonate from quartzite in an area where both are present (a penknife is always useful). And then there is the imbricate zone (Locations 14, 15 and 16), baffling if it had been encountered at the start of the course, but no problem at all if left, as geography and access suggest it should be, until the end.

But to return to LinkedIn. It seems that it is not the discomfort of fieldwork that discourages students but the cost, and that is something that, unless the industries that benefit, and require, a steady flow of competent geologists should step up to the mark, seems an almost intractable problem. In that context, I have a pipe dream. It is that some day the Explorer’s Lodge at Inchnadamph might come on the market, and industry and the universities might come together to buy it, and establish there a residential field centre where future generations of geologists could receive their field training.

It could be called the Janet Watson Field Centre.