In Richard Howarth’s recently published history of geophysics there is chapter concerned with magnetic measurements being taken ‘Into the Field’, in which he notes that the first attempt to make such measurements from an aircraft took place in the Soviet Union in 1936, using an induction coil magnetometer with an accuracy of around +/- 1000 nT.

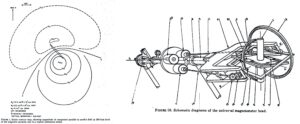

Unsurprisingly, these experiments were not successful, but much better ways of measuring magnetic field were being developed during the 1930s, and these were considered early in the Second World War by the US Naval Ordnance Laboratory as possible means of detecting submerged submarines (Figure 1). The instruments on which this programme ultimately focussed were of a type now known as fluxgate magnetometers but informally referred to at the time as ‘Vacquier magnetometers’, after their inventor, Victor Vacquier, who developed them while working for the research laboratories of Gulf Oil. The basic sensing element is a coil wound around a magnetically ‘soft’ rod, and the measurement is of the component of the magnetic field along its axis. In order to measure total field, three sensors can be mounted at right angles in a gyro-stabilised mount, two of which feed signals to servo motors that align the system so they detect zero field (Figure 2). This automatically aligns the third sensor to read total field, and this technique became standard in airborne operations.

The wartime work was shrouded in secrecy, and the report on the ‘Magnetic Airborne Detector Program’ that was submitted to the National Defense Research Committee in 1946 was originally classified as Confidential. It was not until 1960 that this classification was revoked, and by that time the instrument and its derivatives had already made major contributions to geological science. These arrived to late to appear in the report, but it was noted that the research activity ‘culminated in the AN/ASQ-1 and AN/ASQ-1A systems, both of which were installed and saw active service in numerous patrol aircraft’. The successful use of the system in the sinking of a U-boat in the Straits of Gibraltar is described on its p.64.

A useful contribution to the war effort, certainly, but not, except for the crews on that and other U-boats, not world changing.

Figure 1. Calculated magnetic anomaly produced by a U-boat 200 ft below the sensor. Figure 2. AN/ASQ-1 schematic: (1) Detector element. (2) Oientator plate. (3) Closed gimbal. (4) Open-fork gimbal. (5) Suspending shaft. (6) Fixed bearing. (7)&(8) Stabiliser elements. (9)&(10) Control motors. (12) Pinion. (13) Gear. (11)&(14) Shafts. (15)&(16) Bevel gears. (17) Pinion. (18) Gear. Both figures from the Summary Technical Report of the National Defense Research Committee.

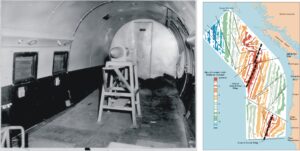

With the war over, thoughts turned to the possible peacetime uses of magnetometry. Vacquier moved to Sperry to work on gyrocompasses, then to the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, where he worked on groundwater detection and finally, in 1957, to the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO). By the time he made that move, the instrument he invented had already made some economically important discoveries, but it was the airborne applications that took centre stage, and In North America surveys were being flown for geology even before the war had ended. Australia, another country with vast areas of poorly exposed rocks, lagged a little behind, but in 1951 the government’s Bureau of Mineral Resources began flying surveys with a modified AN/ASQ-1 magnetometer mounted in the otherwise emptied rear section of a DC-3 aircraft, VH-BUR.

Not only did aeromagnetic surveys rapidly become routine geological tools throughout much of the world but their success led to the wider acceptance of airborne geophysics, and the installation of a wide variety of sensors in an amazing range of aircraft. For airborne applications the fluxgate was superseded after a few decades by more sensitive instruments based on very different physical principles, but it can truly be said to have initiated a step change in applied geophysics.

Is that enough for the AN/ASQ-1 to be described as “The instrument that changed the world”?

That would be going much too far, but there was more to come.

Figure 3. The (rather rudimentary) first installation in VH-BUR. Figure 4. Magnetic stripes north from Cape Mendocino

The application of the magnetic method in marine geology developed much more slowly at sea than in the air. When, in 1951, the Geological Society of America published its Memoir 47, ‘The Interpretation of Aeromagnetic Maps’, there had only been one such recorded use of a magnetometer, a modified AN/ASQ-1 towed in a ‘fish’ behind a survey vessel by the Lamont Geophysical Observatory. A single traverse was made across the Atlantic from Dakar to Barbados, but attempts to repeat this initial success failed, not through any fault in the magnetometer but through failures of the towing cable and connectors. The one successful traverse was made in 1948 but the report was not published until1953, and by that time a much more ambitious series of measurements had been made by Scripps, using the Lamont magnetometer. It had needed a slightly improbable chain of events to make that happen.

In 1951 Ron Mason, then a lecturer at London University’s Imperial College, was granted a sabbatical year, despite having been appointed only four years earlier. He spent that year at Caltech, and in the spring of 1952 he attended the annual meeting of the University of California Institute of Geophysics, held that year at Scripps in La Jolla. As he describes it in Nancy Oreskes book on the history of plate tectonics, some presentations he attended on marine seismology set him thinking about other geophysical techniques that had been or might be used for studying the oceanic crust where, apart from seismology, very little seemed to have been done. In the course of a casual conversation with Russel Raitt, the SIO seismologist, he inquired whether anyone had thought of investigating sea floor structures by towing a magnetometer behind a ship. The conversation was overheard by Roger Revelle, who asked him if he wanted to do it. Mason said yes, and so became the SIO’s magnetometer man. Less than a year later he was on board the SIO’s R/V Spencer F. Baird, recording the magnetic anomalies from Suva to San Diego via Tonga and Tahiti.

The results were not particularly exciting, because it is almost impossible to interpret a single isolated magnetic profile without some additional information, and Mason turned his attention to investigating the magnetic properties of sediment cores obtained off the coast of California, but then an opportunity arose to do some much more systematic work. Bill Menard provided an account of its origin in ‘An Ocean of Truth’

“No more serendipitous relation can be imagined than the needs of the Navy and the discovery of magnetic stripes off the west coast of North America. The Navy wanted to deploy a new very-long-range listening system on the California sea floor in the mid-1950s. It was essential to know the location and size of every seamount that might affect the performance of the system. We were consulted for background advice because of our research on fracture zones and physiographic provinces in the area. I was called back to Washington to talk to King Cooper and associates in the Bureau of Ships, and we discussed the optimum spacing and orientation of the sounding lines. …… As I prepared to leave, King asked if there was anything else that the ship could do underway that would not interfere with running straight sounding lines. I remembered the Capricorn expedition. Ron Mason was still at Scripps working on his red clay cores; I suggested that they let us tow a magnetometer.” (Ocean of Truth, p.72)

Mason took on the job. The survey, in the R/V Pioneer, would be precisely located electronically by LORAN-C, an advanced system developed by the US Coast and Geodetic Survey, and the line spacing would be only 5 miles. No comparable survey existed anywhere else.

The rest, as they say, is history, but it might easily not have been

“…….no one in the Office of Naval Research or any of its advisors could see any point in towing a magnetometer on the Pioneer survey. The U.S. Geological Survey said it would be a waste of money, and refused to fund the magnetic survey. Thus it was that one of the most significant geophysical surveys ever made was wholly financed by the minuscule discretionary funds of the Director of Scripps Institution of Oceanography.” (Ocean of Truth, p.73)

The general lack of interest did, however, have one important side effect, which was that the Navy did not value the results enough to have them classified as confidentials, so they could be published, and a few years later, Fred Vine, Drummond Mathews and, independently, Lawrence Morley provided an explanation of the linear patterns of anomaly they revealed. The Hess-Dietz sea-floor spreading hypothesis was confirmed, and plate tectonics had arrived. The science of geology was transformed.

So was the AN/ASQ-I magnetometer really THE instrument that changed the world? That is too large a claim to make for it, or any other one instrument. But an instrument that, with very little fanfare, completely transformed our view of our world?

Very definitely.